I’m impressed

For the last couple of years, my colleagues and myself have been playing around with AI. I can’t speak for them but from the perspective of a casual user I am very much impressed by the capabilities on display. If you dedicate some time to it you can get a lot of mileage out of AI, it can help you in the way a highly interactive book would help, with vast amounts of knowledge at the tips of your fingers. As long as you are wary of the inevitable hallucinations and the AI’s tendency to get stuck in loops. Because the one thing that we have not yet managed to program in there is the ability to be humble: to realize that no matter how much knowledge you’ve got you don’t know everything. So “I don’t know” is not on the menu. It is not the kind of thing I have seen as output from the various AI offerings.

If you had told me ten years ago that we would be having conversations with a machine at this level today I would have thought it to be impossible, and yet, here we are. The ‘Attention is all you need paper’ combined with Hinton’s persistence paid off immensely, probably more than even the people behind that effort had expected. Current generative AI is able to converse on an immense variety of topics at a reasonably high level.

Professional use

Even so, I would never use its output in a professional setting. When we are hired to do work we are hired to do work, not to come up with prompts and then to let the AI do the work. Anybody can do that, it would feel like fraud to use AI as some kind of shortcut, then we may as well give our customers the prompts.

As a search engine and uniform interface to documentation though, it is unparalleled, as long as you check the output for factual correctness.

Commercializing AI

Because we like playing around with new tech we put together a monster computer with a lot of GPUs and a very large amount of memory. This gives us the capability to run these models in-house and to evaluate their abilities without accidentally leaking our data to the AI providers. What struck me is that in any conversation longer than a couple of lines you end up with one or more times where you have to correct the AI on some point, after which the conversation may stay on the rails a bit longer. But there is always a point where the growing context becomes problematic and of course when you start a new session all of those corrections are forgotten. That plus any kind of formatting instructions regarding the responses have to be repeated over and over again at the beginning of every new session, a kind of ‘system prompt’ at the user level. Running a system like this commercially requires a lot of power, memory, computation and storage for every a single user. I’m fortunate in that I have a lot of solar panels but if not for that my power bill would be astronomical.

And that’s where the data centers and the price of RAM and GPUs comes in. The price of a stick of DDR5 memory must have the smell of onions baked in because when I look I start crying. This will force the AI companies to commercialize it but their avenues to do so are limited, and I’m not sure how they think they are going to survive without doing some kind of rug-pull.

Confidence

What bugs me about the interaction with the various AI models is that they are so incredibly over confident. They are jump-to-conclusion machines that will answer a one line prompt with six pages of plausible nonsense as often as they get it right. The signal-to-noise ratio can be very low and if you’re not careful you will end up reading a lot of self congratulationary bullshit that does not move the needle at all in terms of your understanding or insight. The number of times I’ve seen the word ‘working’ for something that could not work and ‘no handwaving’ followed by a lot of handwaving is pretty high, at least as high as the number of times that I came away with the idea that I had genuinely learned something. It would be great if the current crop of AI used font size or levels of gray to denote the things they are actually confident about and the things that are speculative. This alone would significantly increase its value to me.

When it does not work

The most use I seem to get out of it is when I’m studying some subject that I already know the basics of to increase that knowledge and give hints on fruitful avenues of reading or research. It rarely happens that the interaction with the AI itself gives direct insight on things that are non-obvious. Over the course of the year that has happened probably a handful of times. The more clueless I am about a subject the less use I get out of AI. Conversely, the more I know about something the more I’m irritated at the basic stuff that it - repeatedly - gets wrong and you end up with endless corrections. It is able to pull a massive amount of information up at a moments notice but it will happily forget something that came up only a few minutes ago. This can be quite annoying, but then, whenever I’m annoyed I am also impressed: I am annoyed at a machine for not being able to so something as if it were a person. And it clearly is not, despite all of the language hints that it is.

The Sleaze

Some of the models that are in widespread use are extremely slick at giving the user the impression that they are smart. They will endlessly congratulate and reinforce that the user is a smart person even when they’re clearly not. The paternalizing attitude is so ingrained that even after multiple reminders it will often just find new ways to effectively do the same thing.

The Hive Mind

After playing with something for a while I always wonder: What’s next? Where are we headed? I think the current crop of AI products is useful, but the push towards commercialization will most likely destroy a lot of that utility. The same has happened with all other media that preceded it and I think it is fair to consider AI not so much a new block of interactive content but to see it as a new medium, a way to access information. It got jumpstarted by violating copyright on a massive scale (violating copyright law is what will get individuals into the poorhouse and will get companies very large valuations). But once that was done and the obvious content mountains exhauste the race was on to mine the remainder.

Content that was stored off-line or behind closed access (what are the chances that the likes of Google and Microsoft will be able to resist the lure of your mailbox and your file storage?) and content that was stored in inconvenient forms (books, for instance) all got digitized and gobbled up. The end of that is in sight as well.

But there is one source of fresh, and mostly un-tainted content that will remain: the direct interaction with the AI’s themselves. And this is where the future lies. I strongly believe that endless re-training AI on the conversations it has with actual humans is what will give the AI leaders their edge. This is content that only they have and that gives them a strong signal to help fix their confidence issues and the hallucination problem. Humans are correcting AI, effectively giving very high grade labeled training data every day. And lots of other useful information as well. By moving from a batch learning model with a release every so many months to a continuous learning model where your conversations are first stored as a shell around the original AI release and then later become incorporated into the inner core we will most likely end up improving the AIs we interact with the most.

It’s funny because we have to pay to access the AI which recycles a lot of stolen content and then we have to pay again to be allowed to teach it! Effectively the AI will become a crossbar between the brains of all of the people interacting with it and the closer that gets to real time the closer we will be to an actual hive mind. And deciding to ‘opt out’ will at that point probably make you effectively unemployable, you will be either augmented and expected to deliver or you will be on the dole.

The next decade will be interesting, and if there one thing I’m grateful for then it is that this wave hits me this late in my career, mostly because I wonder if there will still be room for dinosaurs like me, who refuse to have anything to do with AI in a professional setting. No matter how much Google wants to ram it down my throat.

AGI

Another often seen theme is that of AGI, the bigger brother of today’s systems. There is this hope amongst AI proponents that it will be the new frontier, super human intelligence. But I don’t think that that will matter as much. People are already using these systems as though they are AGI, and in that sense the narrow academic or techno definition is irrelevant. What matters is how people perceive it and when you look around you and see people talking to AIs about what they should cook for dinner and relationship advice then it is clear that even if AGI never actually happens it isn’t going to be a blocker to further adoption. We have to be careful that we’re not accidentally creating a new religion as well, the AI worshippers. I think I’ve already met some.

tldr: A small i386 32-bit protected mode multi-tasking operating system modeled after QNX

–

What is Unite?

Unite is an operating system in which everything is a process, including the things that you normally would expect to be part of the kernel. The hard disk driver is a user process, so is the file system running on top of it. The namespace manager is a user process. The whole thing (in theory, see below) supports network transparency from the ground up, you can use resources of other nodes in the network just as easily as you can use local resources, just prefix them with the node ID. In the late 80’s, early 90’s I had a lot of time on my hands. While living in the Netherlands I’d run into the QNX operating system that was sold locally through a distributor. The distributors brother had need of a 386 version of that OS but Quantum Software, the producers of QNX didn’t want to release a 386 version. So I decided to write my own. Luck had it that I ended up in Poland and that the lack of work there meant I could spend a lot of time on this (life was super cheap there back then compared to my savings). In the space of about a year I wrote a proof-of-concept kernel using DJGPP and a very kludgy development system that required me resetting the system after every failure. And there were lots of failures. Thousands of them, until, finally, one day I had a very rudimentary kernel and an ‘idle’ appliation running on top of it.

The next couple of years, until February 1994 (right after my first child was born and I decided I should probably get serious about earning money) I steadily improved on the original until it had a full complement of tools, was self hosting and came with a window manager and some graphics demos.

Why release this now?

When Linux was still very young, in 1992, there was a now infamous dispute between Andrew Tanenbaum, of MINIX fame and Linux Torvalds. The stakes were high: Tanenbaum thought Linus was wasting his time and talent building yet another macro kernel, he argued that micro kernels - even with a speed disadvantage - still have an edge in reliability and in speed of development. I agreed with Tanenbaum, but did not agree that MINIX was the way to go, I’d already seen QNX, and worked on my own variation on that theme and thought it was lightyears ahead of MINIX.

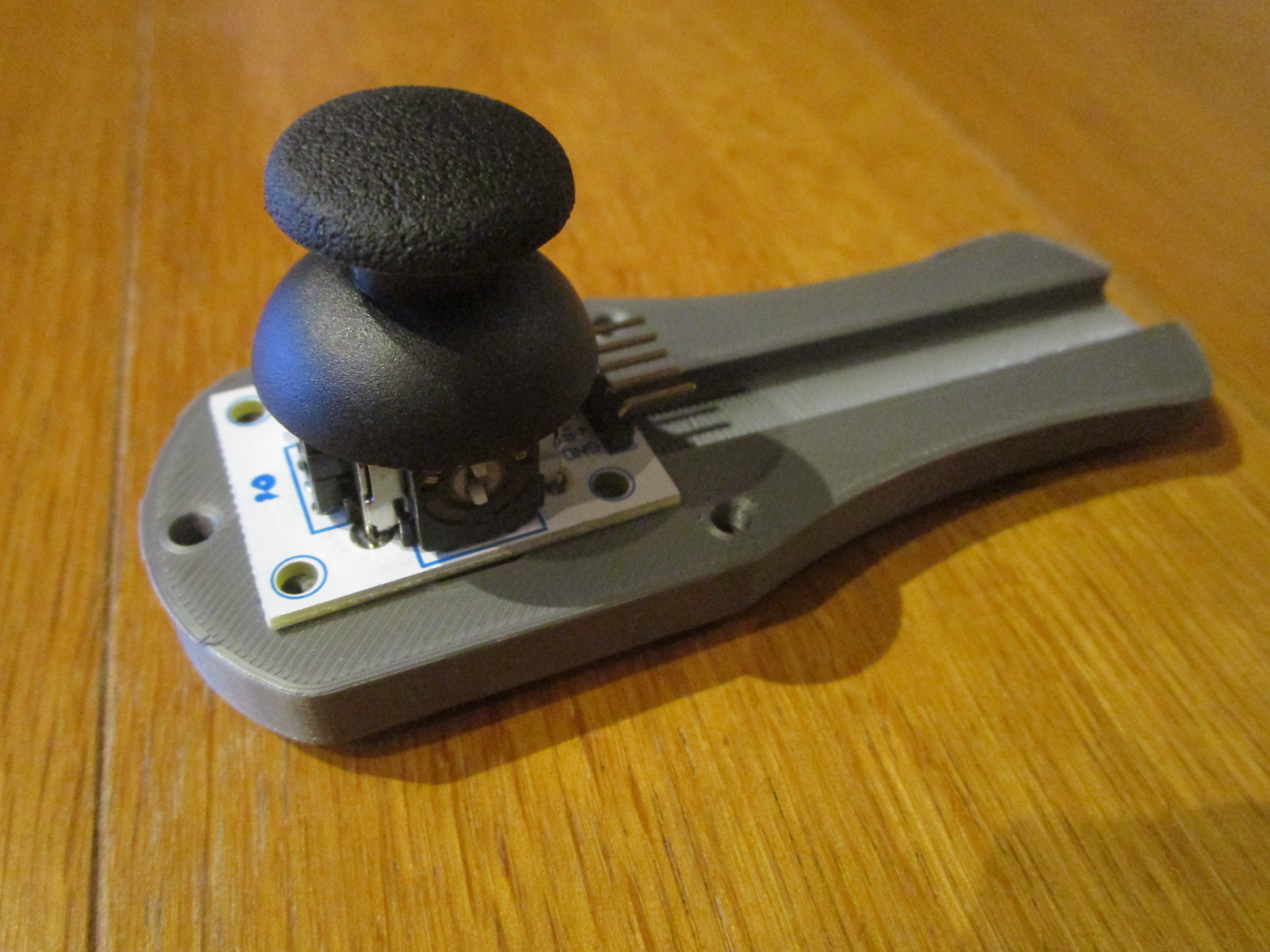

For the longest time this project sat on my hard drive in a state in which it could not run. The hardware that it had originally been developed on had died and I had never seen fit to spend more time on it to keep it bootable. Until the start of the fall of 2025, a good 30 years later, when I talked about it with my colleague I had not thought about putting any effort into a revival. In the meantime, a lot has happened. 32 bit systems are now already past, we’re on 64 bits now and 32 bit systems are usually doing only embedded stuff. We also have virtual machines, a luxury that my 30 year prior self would have happily traded a limb for, this makes development of such low level code a lot simpler than having to dive under the table every three minutes to hit the reset button. At some point this became such a routine that I hooked up a sustain pedal footswitch so I didn’t have to dive under the desk all the time.

So with modern tooling and the arena no longer vying for ‘the next best desktop solution’ I figured I should try to see if there is any life in it. Micro Kernels are fun to hack on: everything except for the core message passing task and scheduler is a user mode program and you can change it as easily as you can change any other program. That makes them unique and I think that this kind of hacking is now, especially with the more powerful embedded platforms within reach of just about anybody. The fact that it is a real time OS makes it much easier to work on hardware that requires guaranteed response time from the OS, there are 16 different priority levels and they offer very fine grained control over which tasks can be interrupted by which others.

Reviving an OS that hasn’t run in 30 years

This was a bit of a challenge. It took about two weeks, there were a couple of lucky breaks. The first was that I had not really done any cleaning of the repository where all this code was stored, so I had quite a few binaries that could run if I had a working OS. The second was that there was an image of a boot floppy. Between those two I managed to get the system booted under VirtualBox using a RAM disk. Some days later I had a working LBA capable hard drive, which I then populated with the contents of the ramdisk, and from there it was relatively quick work to recover the rest of the system.

The part that still eludes me is the bootfs.com program, this is the filesystem aware portion of the bootloader, that is loaded by the first stage on the boot floppy. There is some magic in there that for some reason does not play nice with the recovered version of TurboC, there is a chance I’m simply doing something wrong but I have not been able to successfully recompile that program and to get it to work so for now the system still boots from that original floppy image. But that’s fine, it’s not real hardware anyway and I’m sure if you really want to you can make it work again, all the pieces are there, I’ve added a VM disk image that should allow you to work on bootfs as well using freedos and some old binaries. Bootfs.com is a 16 bit real mode tiny memory model file that shuttles back-and-forth between real and protected mode to load all of the operating system components. It could boot from the hard drive as well (there is a ‘boot’ program to help you install the bootloader on an image) and like that you could do away with the floppy drive.

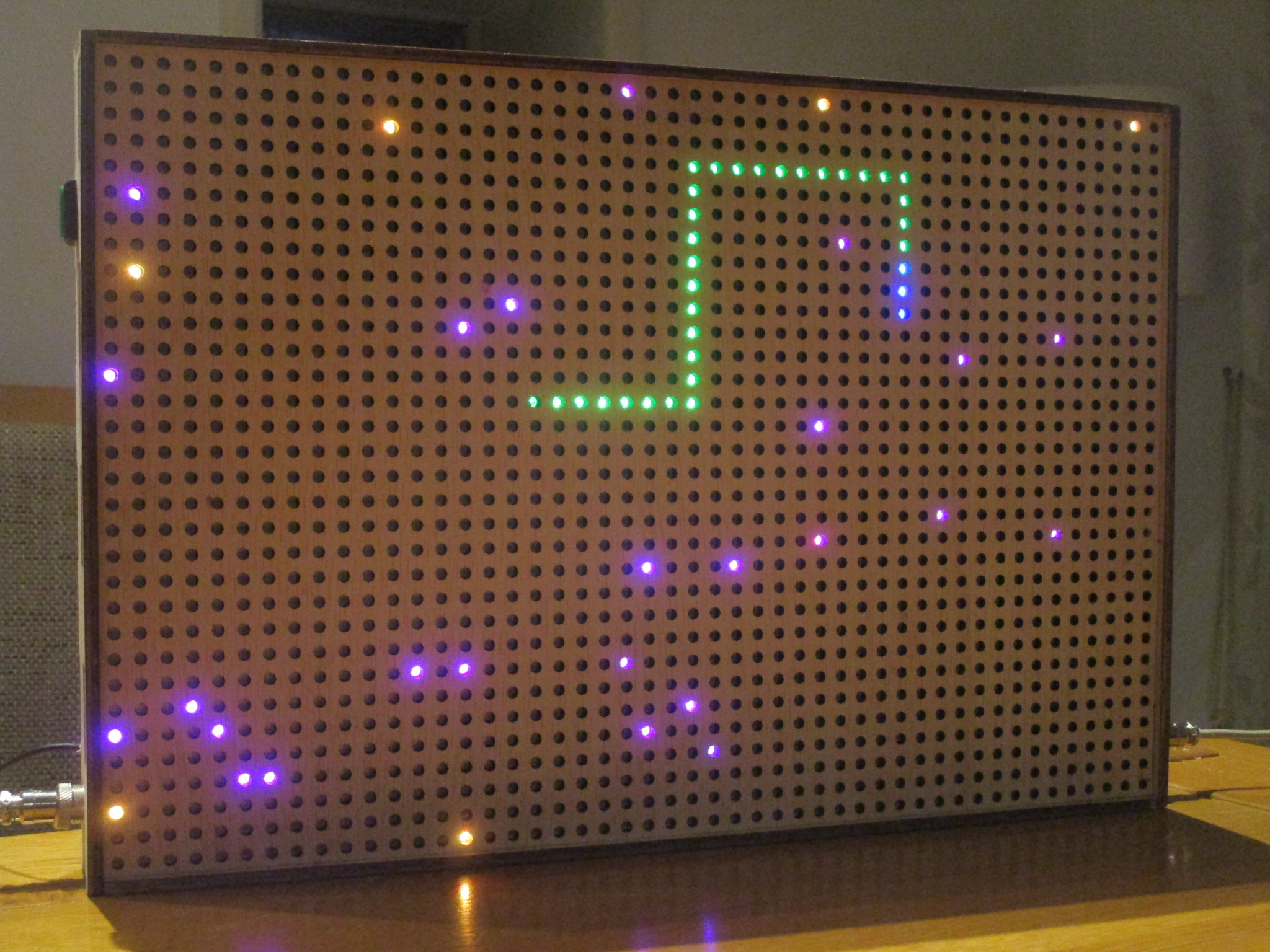

What does it look like?

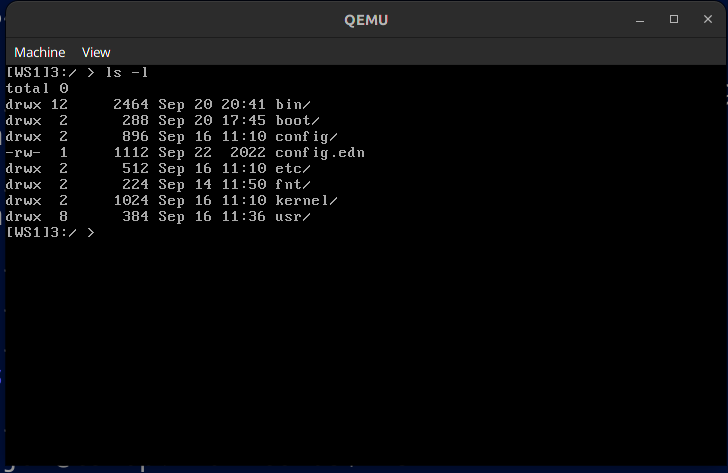

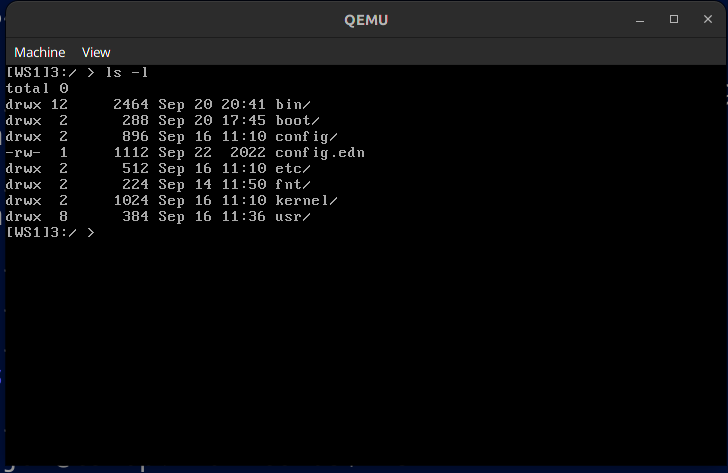

Well, it looks like any old boring text mode operating system. There is the usual complement of utilities, a C compiler (and a C++ compiler), both are ancient but they work. There is the source tree in /usr/kernel.src and /usr/src as well as the usual unix like locations for binaries and such. There is a shell. There is some networking support but - again - I have not been able to resurrect this, and I can’t get the emulated COM ports to work either, which would have been nice as a way to move data in and out (for instance, using SLIP).

Quick start user guide

Install QEMU. Download the distro (see below). Unzip the distro file, and cd to unite/os, after that run ./unite.sh and you should see a virtual machine boot up in text mode. After it has booted and you’ve clicked in the VM windows to give it keyboard focus hit alt-f2 to move to another console (one where you can type commands) and type ‘cd 3:/’ to move to the hard drive. If you’re used to some variety of Unix you will feel mostly at home but note that ‘cli’ (command line interpreter) is not a regular shell. Interesting bits to look at are in 1:/boot/config.0 and of course the directory tree of drive 3:/ (the simulated hard disk). The file system is a very much stripped down version of the MINIX file system as it was at the time, it was meant to be replaced but I never got around to it. If you type ‘tsk’ you can see which tasks are currently running and ‘sac’ gives you a rudimentary system activity monitor. If you’ve used QNX at all in the past you will feel right at home.

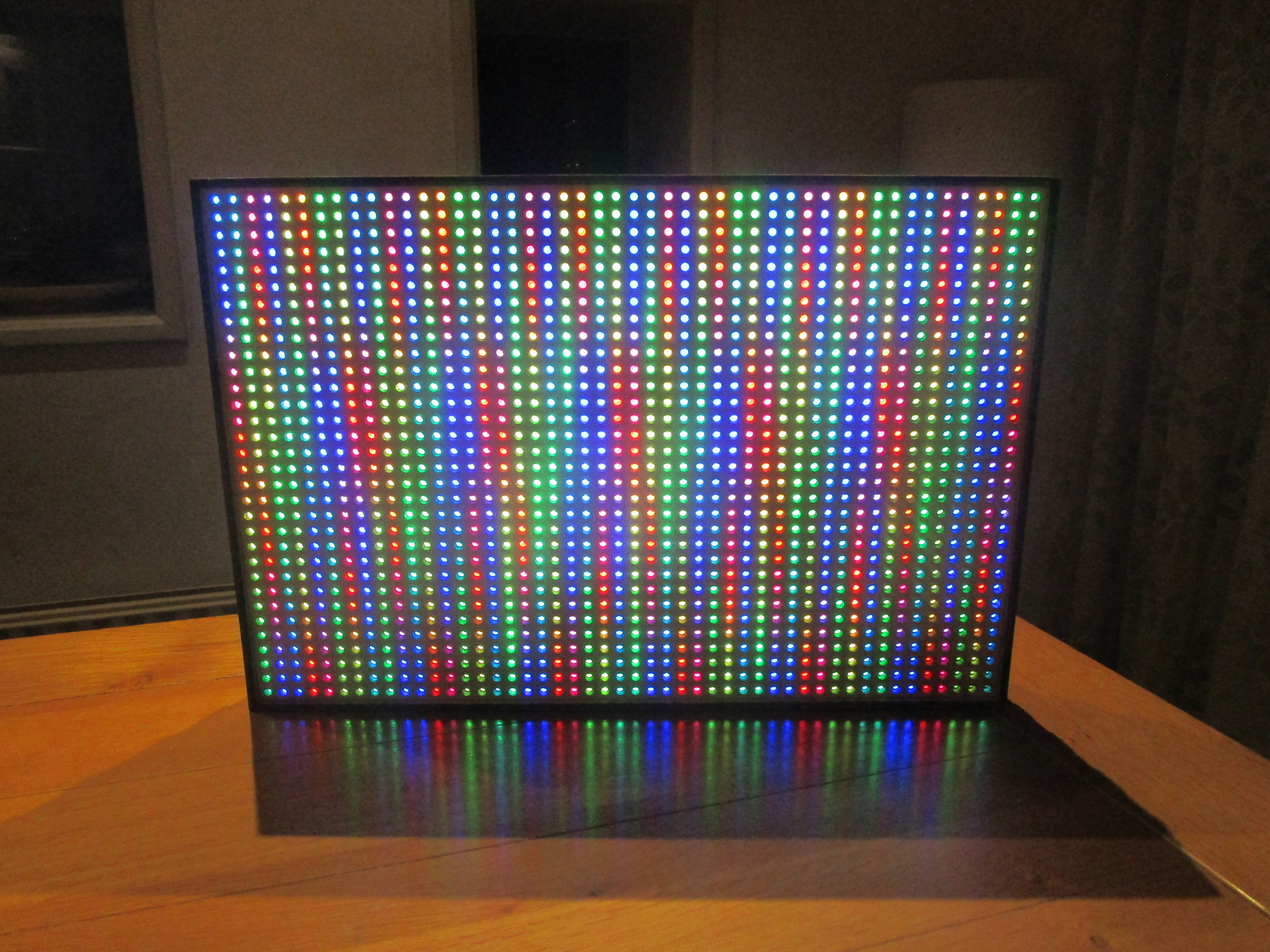

Unite does not have the concept of a user, it is very much a single user OS but that single user can have multiple sessions. There is also a graphics mode, you can activate it by changing the ‘mode’ line in 1:/config/config.0 to ‘mode 16’ but I’d advise against that until you have the COM ports working and are able to type commands through there so you can see what you’re doing. If you are really adventurous: make a backup of the fda.img file; change that mode line and reboot. You’ll end up in a completely blind graphics mode. You should then type the following (all blind so you won’t know if you did it right or not until it works): ‘cd 3:/’ ; ‘cd bin/gp’ ; ‘ontty /dev/console.4 gp’ ; ‘ontty /dev/console.4 qwm’ ; ‘ontty /dev/console.4 qwmdesk’ (now the screen should change) ; ‘ontty /dev/console.4 qwmcalc’ (now you should see a small calculator, it would work if you had mouse/keyboard support but you don’t) ; ‘ontty /dev/console.4 qwmline’ (which should show a bouncing line demo).

Now you have a problem: if you reboot the system it will go right back to that graphics mode. So now you want to restore that fda.img backup you made above.

The Distribution

The operating system is distributed as a torrent:

magnet:?xt=urn:btih:bb01f5651944948b1b705ae4efa5ab5578bdee00&dn=unite.zip

The torrent contains a single zip file that you unpack, then you follow the instructions above.

Some notes:

I have only tested this under Linux using VirtualBox and Qemu, I have not ran it under a Windows VM or on real hardware and you may run into issues if you do.

there is no networking, this is probably the first thing that really needs doing

the COM ports don’t work yet (this seems to be an emulation issue, I have yet to see a single byte in or out)

the mouse driver (mp) does not work (it relies on a mouse plugged into a COM port, see above)

the version of vi that is in /bin seems to add random cruft to files, I have not been able to figure out yet what the reason for that is.

there is an alternative editor ‘e’ that does work, and that I wrote back in the stone age

this is not/was not an effort at making something that is ‘secure’, if you plan on using this be very much aware of that and that you are most likely going to open yourself up to being compromised within seconds if you hook this up to the big bad internet. I was already very happy that I got as far as I did. But the Micro Kernel concept lends itself well to modification and you can start hacking on the kernel pretty much immediately, it is that simple.

it is i386 protected mode only right now if you want another CPU or 64 bit then you have a lot of (fun!) work ahead of you.

I have plenty to do and will not be available to manage this project or to even administer it, the source code is my full and only contribution, from here on in if you want to do something with it you are essentially on your own (or with your friends!), I have a lot of other stuff on my plate that takes precedence, so apologies for that but I still hope you find this useful.

License:

There are a lot of pieces that have been cobbled together from various other distributions, these were all made available at the time so in theory they should be fine to use but I have not verified whether any of those licenses have since been retracted or modified. Whichever party contributed the code still has the rights and this release is under the exact same license as under which the code was originally released in the early 90’s. The remaining code, the part of the code that I lay claim to (the core OS, the editor and the graphics library) I herewith place in the public domain, you can do with it whatever you want, as long as you credit the project and include a link to this page so others can start off from the same point. If you release an interesting derivative let me know and I’ll add a link to this page.

Credits:

- Henri Groenweg wrote the memory manager

- Marcel Wouters wrote the console and display driver

- DJGPP, by DJ DeLorie was the key to being able to start this at all

- QNX served as a very useful model and inspiration

- MINIX, provided in source code made it possible to have a file system; so thank you Andrew Tanenbaum, this made a massive difference

Screenshots

A short video showing the graphics mode

tldr: limit your GPUs to about 2/3rd of maximum power draw for the least Joules consumed per token generated without speed penalty.

–

Why run an LLM yourself in the first place?

The llama.cpp software suite is a very impressive piece of work. It is a key element in some of the stuff that I’m playing around with on my home systems, which for good reasons I will never be able to use in conjunction with a paid offering from an online provider. It’s interesting how the typical use-case for LLMs is best served by the larger providers and the smaller models are just useful to gain an understanding and to whet your appetite. But for some applications the legalities preclude any such sharing and then you’re up the creek without a paddle. The question then is: is ‘some AI’ better than no AI at all and if it is what does it cost?

What to optimize for?

And this is where things get complicated very quickly. There are so many parameters that you could use to measure your systems’ performance that it can be quite difficult to determine if a change you made was an improvement or rather the opposite. After playing around with this stuff a colleague suggested I look into the power consumption per token generated.

And that turned out - all other things being equal - to be an excellent measure to optimize for. It has a number of very useful properties: it’s a scalar, so it is easy to see whether you’re improving or not, it’s very well defined: Joules / token generated is all there is to it and given a uniform way of measuring the property of a system you can compare it to other systems even if they’re not in the same locality. You can average it over a longer period of time to get you reasonably accurate readings even if in the short term there is some fluctuation.

You could optimize for speed instead but for very long running jobs (mine tend to run for weeks or months) speed is overrated as a metric, but for interactive work it is clearly the best thing to optimize for as long as the hardware stays healthy. And ultimately Joules burned per token is an excellent proxy for cost (assuming you pay for your energy).

Creating the samples

So much for the theory. In practice though, measuring this number turned out to be more of a hassle than I thought it would be. There are a couple of things that complicate this: PCs do not normally come with easy ways to measure how much power they consume and LLama doesn’t have a way to track GPU power consumption during its computations. But there are some ways around this.

I started out by parsing the last 10 lines of the main.log file for every run of llama.cpp. That works as long as you only have one GPU and run only one instance. But if you have the VRAM and possibly multiple GPUs this will rapidly become a hot mess. The solution is to ensure that every run pipes its output to a unique log file, parse the last couple of lines to fish out the relevant numbers and then to wipe the log file.

Sampling the power consumption was done using a ‘Shelly’ IP enabled socket, it contains a small webserver that you can query to see how much power is drawn though the socket. It’s not super precise, secure or accurate but more than good enough for this purpose. Simply hit

http://$LANIPADDRESS/meter/0

and it will report the status of the device as a json object, which is trivial to parse. Nvidia’s nvidia-smi program will show you the status of the GPUs and report their current power draw. Subtract that out and you’re left with just the CPU, RAM, MB and the drives.

Experiment

You then let this run for a while to give you enough samples to draw conclusions from. In order to figure out what the sweet spot of the setup I have here is (right now 2x 3090, i7) I stepped through the power consumption of the GPUs in small increments. 25 Watts per step, with a multi-hour run to get some precision in the measurements. Nvidia cards have an internal power limiter that allows you to set an upper limit to their consumption in Watts for a dual GPU setup the command line is:

nvidia-smi –power-limit=$Wattage –id=0,1

Just replace $Wattage with whatever limit you desire, but keep it above 100 and below the maximum power draw of the GPU for meaningful results.

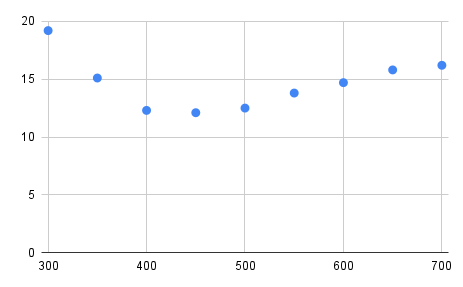

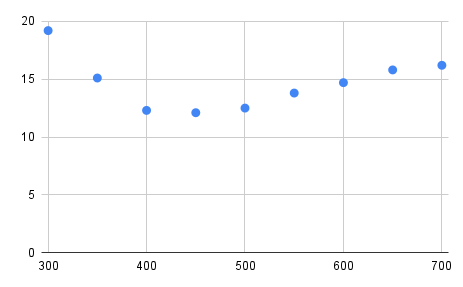

Doing this for a series of steps using the Llama 13B 5 bit sampled model (which uses about 10G of VRAM), running four instances of llama.cpp concurrently (so two on each card) for an hour per step to reduce sampling inaccuracy gives the following graph of power consumption limits of the GPUs (horizontal) vs Joules consumed per token generated (vertical):

In tabular form:

GPUs (W) tps J/token GPU Temp (W)

300 27 19.2 43

350 35 15.1 48

400 48 12.3 50

450 52 12.1 53

500 51 12.5 53

550 49 13.8 55

600 50 14.7 57

650 50 15.8 60

700 50 16.2 63

Conclusion

The ‘sweet spot’ is pretty clear, the graph starts off on the left at about 19 Joules per token because the simple fact that the machine is on dominates the calculation. Not unlike a car that is idling or going very slow: you make no progress but you consume quite a bit of power. Then, as you ramp up the power consumption resulting in more processing efficiency increases fairly rapidly, up to a point. And after that point efficiency drops again, this is because now thermal effects are dominating and more input power does not result in that much more computation. If you live in a cold climate you may think of this as co-generation ;) In an extreme case you might run into thermal throttling, which is because of the way llama.cpp handles the interaction between the CPU and GPU just going to lead to a lot of wasted power. So there is a clearly defined optimum, for this dual 3090 + i7 CPU that seems to lie somewhere around 225W per GPU.

The efficiency is still quite bad (big operators report 4-5 Joules / token on far larger models than these), but it is much better than what you’d get out of a naively configured system, resulting in more results for a given expense in power (and where I live that translates into real money). If you have other dominant factors (such as time) or if power is very cheap where you live then your ‘sweet spot’ may well be somewhere else. But for me this method helped run some pretty big jobs at an affordable budget, and it just so happens that the optimum efficiency also coincides with very close to peak performance in terms of tokens generated per unit time.

Caveats

Note that these findings are probably very much dependent on:

- workload

- model used

- the current version of llama.cpp (which is improving all the time) and the particular settings that I compiled it with (make LLAMA_FAST=1 LLAMA_CUBLAS=1 NVCCFLAGS=“–forward-unknown-to-host-compiler -arch=sm_86” CUDA_DOCKER_ARCH=“sm_86”)

- Hardware

- GPU (Asus ‘Turbo’ NV 3090)

- CPU (i7-10700K stepping 5)

- avoid thermal throttling (which would upset the benchmark)

- CPU and case fans set to maximum (noisy!)

- GPU fans set to 80%

- ambient temperature (approximately 24 degrees in the room where these tests were done)

- Quite possibly other factors that I haven’t thought of.

Please take these caveats seriously and run your own tests, and in general don’t trust fresh benchmarks of anything that hasn’t been reproduced by others (Including this one!) or that you yourself haven’t reproduced yet. If you have interesting results that contradict or confirm these then of course I’d love to hear about it via jacques@modularcompany.com, and if the information warrants it I’ll be more than happy to amend this article.

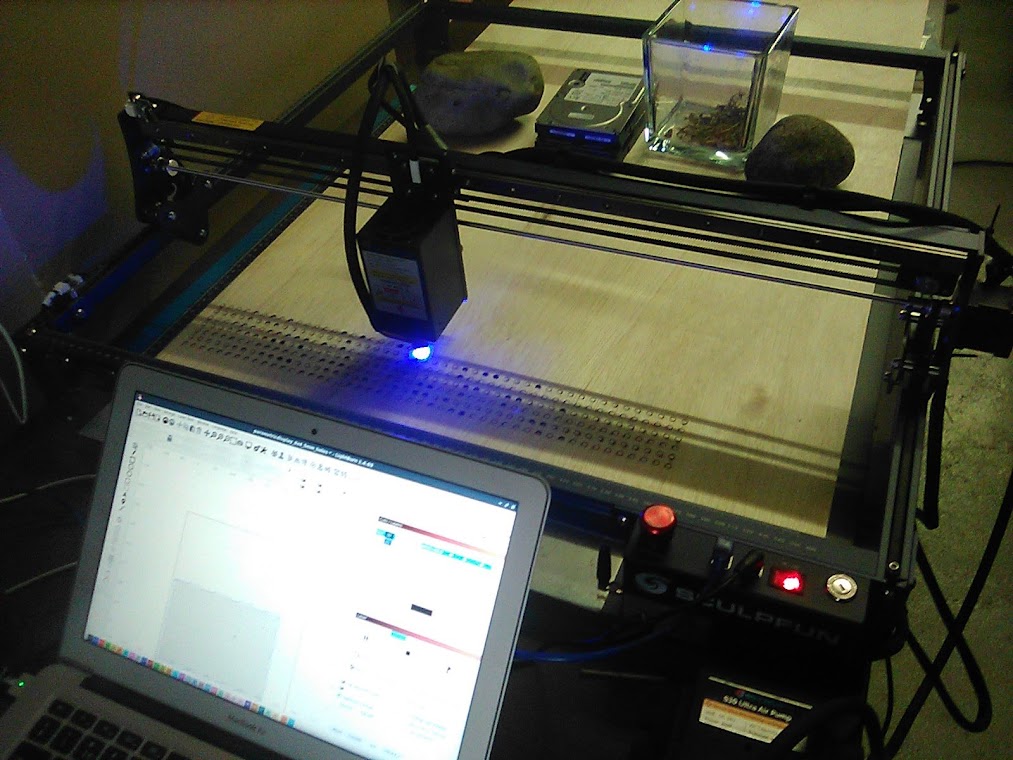

CNC Lasers for cutting and engraving

Laser cutters can injure or blind you permanently if you do not follow safety procedures! This post is an attempt to collect all of the information that I’ve gathered over the last year or so regarding budget laser cutters. There are no affiliate links on this page, I have no ties to any of the companies mentioned here other than that I’m a reasonably satisfied customer of some of them. If you have corrections or suggestions for expanding this article or if you want to contribute information for the materials section please contact me via jacques@modularcompany.com . The intention is to make this a ‘living’ document and to expand it and update it over time.

LASER CUTTER / ENGRAVER SAFETY

DO NOT STARE INTO LASER WITH REMAINING EYE

Sounds funny, doesn't it? Well, it isn't. Before you read the rest of this document I would love it if you read through this safety section in its entirety. If I could I'd add an exam that you have to pass before you can read the remainder but that would be annoying. So I will trust you to do exactly that: read this text as if your eyesight and general health depend on it because they do.

Lasers are dangerous. They are both dangerous because of the concentrated light that they emit and they are dangerous because of the fumes given off during the operation of the machine. This is why you can use them to cut and mark materials with in the first place. They can start fires and they will do so exactly when you're not monitoring the machine. There is no such thing as a safe laser that can cut or engrave material in any useful capacity. Do not let yourself be taken in by manufacturer marketing materials that show open frame lasers or enclosed lasers that do not vent to the outside.

Laser safety is a major subject in its own right and using one responsibly is more work than throwing caution to the wind. But your eyes, your family, your pets and your insurance company, and ultimately yourself are going to be much happier if you take these warnings into account. If you don't understand something in the safety section play it safe: don't do it. If you think something in this safety section is wrong, needs improvement or better wording by all means, contact me: jacques@modularcompany.com and I'll work with you until both you and I think it is the best possible because this is the most important part of this document. I'm most grateful to everybody that contributed safety related advice from the HN comments on this article, specfically and in no particular order: 0xEF, 542458, msds, avar, cstross, sen, cyberax, nullc, rocqua, mittrhowaway, jfim, elihu, kragen, FuriouslyAdrift, iancmceachern, xyzzy123 and CarRamrod.

- NEVER use an open frame laser ‘as is’ a laser needs an enclosure

- even if the manufacturer shows a video or a photograph depicting the machine in a dwelling

- Lasers should not be used in living spaces

- Children and pets should be kept away from an operating laser

- Lasers should never be operated unattended

- enclosures should be ventilated

- the exhaust system should be capable of removing a multiple of the volume of the enclosure every minute as well as the total volume of air injected by the air assist if your machine has this feature, you want ample capacity here.

- the exhaust system should be leak free and vent (filtered!) into the environment away from any occupied structure

- any windows in the enclosure should filter out the wavelength of the laser you are using (but better to use a camera!)

- enclosures should be ventilated even if the manufacturer claims otherwise.

- enclosures should have an interlock

- as soon as the enclosure is opened that should count as an e-stop, the machine should be disabled completely

- enclosures should have an e-stop switch on the outside that cuts all power to the system

- if possible an optical fence can create a perimeter around the machine that can’t be entered when it is running

- enclosures should be fire proof

- the bottom of the enclosure should be able to withstand a sustained direct hit from the laser head at its lowest possible position at maximum power while not in motion.

- there should be a fire extinguisher of sufficient capacity near the enclosure

- there should be a fire detection system.

- some materials should never be cut or engraved

- do not cut or engrave PVC under any circumstance, using PVC will create hydrogen chloride which is super dangerous

- do not cut or engrave Polycarbonate unless you can work under an inert atmosphere such as nitrogen

- do not attempt to cut or engrave leather, the smell is awful and it can be very dangerous

- if you do decide to cut or engrave leather make sure it hasn’t been tanned with Chrome

- depending on the wavelength the laser light itself may be more or less dangerous, the safe power limit depends on the wavelength

- Damage from laser light may not be readily apparent at first because your brain is very good at working around such damage.

- You wil need to get the best quality safety glasses for the wavelength of your machine that you can afford, and you need to procure them from a reliable source. Do not skimp on this, even if your last name is Scrooge. Green is almost certainly the wrong color for your glasses, orange/brown is what you are looking for and glasses that absorb the beam will be damaged (smoke, burning) by a direct hit. Think of it this way: if the glass doesn’t aborb the beam effectively that means the light gets passed on to your eye!

- you will always need to wear these when near the laser is powered up.

- that still does not obviate the need for an enclosure

- the best way to observe a laser cutter is indirectly, through a camera, get a camera!

- It’s not just direct hits of the beam emerging from the laser aperture that are dangerous, a reflection can do serious damage at these power levels

- Visible light lasers, which includes most cheap diode lasers, anything between 380 and 750 nm can give a false sense of safety.

- You can see the beam.

- But if you can see it it may be too late already, anything over 1 mW is dangerous

- This makes the light hard to block

- They may ‘leak’ at other frequencies as well making the light even harder to block.

- Fiber lasers using IR at 1064 nm are probably the most dangerous in the sense that your eye will focus the light just fine but there is no blink or avert reflex

- On deep infrared (CO2) machines the beam will be invisible

- your eye(s) will be damaged before you are even aware of it

- but the wavelength itself is a bit safer, damage will not be immediately catastrophic

- if your machine has a ‘pilot laser’ you’ll have an idea of where the invisible (and much more powerful) IR beam is

- So any laser of sufficient power to cut or engrave materials should be enclosed and shut off automatically if the enclosure is opened.

If any of the above items make you reconsider using a laser cutter/engraver that is perfectly fine, you may be better off joining a local makerspace where they have a machine set up with all of the safety requirements covered (hopefully!). It’s a valid alternative to having one set up in your own workspace.

Introduction

CNC gear has been getting cheaper and cheaper over time, since the 1980’s when I first encountered it. But laser cutters for the longest time refused to join the trend, they were very expensive, fragile, large, heavy and consumed a ton of power. That all changed to the point that today you can buy functional CNC laser cutters and engravers for less than $1000. Obviously these aren’t going to punch through thick steel like their industrial cousins do, but for cutting wood and various other materials as well as to engrave text or images on suitable backgrounds they perform remarkably well.

This article attempts to give a lot of background material to help you get started if you already have one of these or if you are considering buying one. If you haven’t bought a machine yet I’d recommend you read the article in its entirety before pulling the trigger on a particular machine. This is especially important in light of the pretty high pressure sales tactics that some of the manufacturers of this gear employ, keep in mind that you are buying a tool that in industry would require you to go through a required safety course and which would not operate without a large amount of safety measures including interlocks, optical fences and other tricks of the trade to keep the operators safe. Educating yourself a bit before bringing this kind of kit into your home is going to save you from possible injury, a ton of hassle and reading is free.

Laser cutters are of the class ‘subtractive manufacturing’, which means in technical terms that they shape the work piece by removing those bits that you do not want. In this sense they are much like other cutting devices such as rotating knife cutters, tool-and-die cutters, water jet cutters and plasma cutters. The main differences are that compared to rotating knife cutters they cut deeper, compared to tool-and-die cutters that there are no setup costs, compared to water jet cutters that they are relatively cheap and tend to char the edges of the piece to be cut slightly if it is combustible and that compared to plasma cutters you can also cut material that is non-conductive. This makes lasers the cutting tool of choice for a wide variety of materials, and it is precisely this versatility that makes them an excellent tool for hobbyists and the ‘maker’ crowd. And just like those other tools they are also excellent in producing large amounts of scrap, this isn’t a 3D printer where 97% of your input material becomes your work product, it’s not rare to have 20 to 30% scrap which you will need to dispose of.

History

Laser cutters have been around since 1965, coincidentally the year that I was born. But even in the mid-80’s to find a laser cutter in the wild was a rare occasion, especially because they were horrendously expensive. The reason for that expense is that a laser cutter is on two extremes of the technology curve at once: on the one hand it is a machine that carves up various materials and does so by using energy densities that you normally do not encounter on earth, on the other hand it uses absolutely incredibly precise optics for doing so. And on those first lasers the optics were impressive indeed: water cooled glass jacketed quartz tubes that output the laser beam across free space to a mirror mounted on a carriage for the X-axis, then to another mirror mounted on the Y-axis and finally down a focusing lens onto the material.

Much later these found some competition from so called fiber lasers, a variation that uses a solid state laser and a fiber amplification stage to create very small spot sizes for a much more efficient process able to cut more and sometimes thicker materials for a given power budget.

The semiconductor industry, which gave us diode lasers without any optics other than small mirrors mounted in the head to collate the beams and a focusing lens are the main driver behind the orders of magnitude in cost reduction, and these as well as smaller and lighter versions of the industrial machines mentioned above are the ones that you are most likely to encounter as a hobbyist or small business that wants to get into CNC laser work.

What you can buy

There are a ton of different companies offering laser gear, typically made in Asia, with or without an enclosure and of varying quality and power. At the time of this writing a typical diode based laser can be had for well under a thousand dollars. From a practical point of view these are functional tools, but from a safety perspective they are not usable at all, they’re excellent fire starters and are able to do you (and your eyes) great damage. If you want to work with these machines in a responsible manner you’ll need to do some work. It is probably more productive to think of most of these products as kits and starting points rather than as the finished article, even if they do work out of the box (usually after assembling them).

The most important parameters to look for when selecting a laser cutter are: optical output power and head construction, wavelength, cutting bed area, air assist, accuracy, cutting speed, enclosure and type of laser.

Optical Output Power & Head construction

The optical output of a laser cutter is measured in Watts. There are some manufacturers that advertise with the electrical input power of the device, but since lasers are quite inefficient this wrong foots the buyer into thinking they have bought a machine that is much more powerful than it actually is. Most manufacturers of cheap diode lasers tend to exaggerate a bit even if they do specify optical output power. A typical industrial tube laser or fiber laser of several thousand Watt will cut about 10 mm worth of mild steel. So it should be clear that an entry level diode laser of 40 W or so tops isn’t going to be doing much cutting in metal (even if the wavelength was optimal, which it really isn’t). And it also should be clear that a 5W laser isn’t going to cut much of anything and if it does that it will do so quite slow. A typical diode laser head contains one or more laser diodes, a set of mirrors and lenses to combine the output of all of the diodes and a focusing lens that aims the laser diode output at (hopefully) a single small spot on the work piece. The typical arrangement of all of the diodes within the head is a critical part in both the spot size as well as the depth to which the machine will be able to cut: as you get further away from the focal point the chance of the individual beams diverging increases and that will reduce the available power and increase the spot size. It may also cause the spot to be asymmetrical, for instance a spot can be wider than it is long which will make the machine penetrate material in one direction and barely scorch it in another! For any given power output fewer diodes is better because you’ll have a smaller spot size where that power is concentrated, but likely your diodes will run hotter and have a shorter operational life.

So the amount of raw optical power available and the geometry of the head is critical in deciding which machine you will buy. A typical high efficiency laser diode for cutting applications is 5 to 6W. For a 30W machine you can assume five or six diodes, depending on the make (and whether or not the numbers are accurate…). A powerful cutter head will usually have a small fan attached to forcibly cool the diodes to keep them below the temperature at which they self destruct. This is a very important feature and if the fan ever gets blocked or fails the laser head will die in short order. Bluntly: more power is better. You’ll cut either deeper or faster and there will be materials that you suddenly can cut instead of not at all. 5 or 6W machines will have a single diode and a very nice and tight spot. Above that you’ll have two or more diodes and an ever decreasing return on that extra theoretically available power. I’m not sure what the practical upper limit is but I already find that the spot size of a 6 diode factory aligned array laser is sub-optimal. It doesn’t perform six times better than a 5W single diode, more like three to four times better, and there is more spillover near the edge of the cut, especially in the plane the diodes are mounted in.

The output spot size is a very important factor to consider, a larger (less tightly focused) spot size means more overspill and a wider cut. You need to compensate for that in your design if you want to construct things that are solid, typically on the order of 0.1 mm press fits will have enough friction in them that you won’t even need glue. Most diode based lasers cut with the spot size that is so closely focused that near the surface of the work piece the so called ‘kerf’ is only about 0.4 mm wide. Deeper in the cut this can get a bit wider, this effect will be more pronounced when you cut thicker material because the beams that converge on the focal point will diverge beyond it. Even so, my ‘30W’ (take that with a grain of salt) laser head will happily cut 18 mm thick softwood and softwood based plywood, which I find nothing short of incredible. It’s not super fast at those thicknesses, 250 mm/minute (about 10”) on a good day, but it goes and if you’re patient you end up with very usable work pieces. And 18 mm is thick enough for actual construction pieces.

A valid alternative to buying a new machine, especially if you are looking at this to start a business is to buy a second hand industrial machine, either fiber or CO2 depending on your needs. These are not for hobby use, heavy, require a lot of power and they’re large. But from a throughput perspective they will leave the hobby machinery in the dust. Evaluating such a machine will require some expertise, you may want to find a buddy with relevant experience to help guide you and protect you from buying a very large doorstop. Parts and service will be quite expensive. You could still buy a cheap diode laser to start with to gain experience and to try your designs (assuming that the cutting capacity is sufficient), but in the long run the industrial machine is probably a better investment.

rstop

Wavelength

The wavelength of a laser is the characteristic that defines the color of the laser. Typical diode lasers range from 400 to 800 nano meters, but more typically between 400 and 470 nm, corresponding to violet to blue in the visible spectrum. For some materials this works well, for others less so because they are able to reflect these wavelengths resulting in most of the power not being absorbed by the work piece. Longer wavelengths tend to do better for more difficult materials (such as metals) but there really is no diode laser that can cut metal reliably or at any usable thickness. You may be able to cut very thin steel foil with them. Fiber lasers typically have a wavelength of 780 to 2200 nm, which is infrared to deep infra red, very suitable for cutting metals. They are super dangerous if not properly enclosed because you still focus but won’t blink or look away. CO2 lasers range from 9.3 um to 10.6 um, much longer wavelength than either fiber or diode lasers. On the plus side that makes diode lasers moderately safer for use by people that haven’t been specifically trained: you can see the beam and if you can then you at least have a chance to block it. Diode based optical lasers are in some ways more dangerous than their industrial IR counterparts. For one they usually ship without an enclosure, so there are no interlocks that will disable the laser if the user gains access to the guts of the machine. For another the visible nature of the laser beam makes it harder to block and there may be leakage into other parts of the spectrum making them even harder to block. On industrial infrared and deep infrared lasers the beam is invisible and the damage will be done before you are even aware of it but the machines are properly enclosed and have safety interlocks. If you ever get an infrared head for your laser get one that has a visible light pilot laser to make sure that you know where the beam is. Laser light can reflect in the most crazy ways and any kind of concentrated escaped light can be quite dangerous. I know this all sounds alarmist but this is a very real issue that you should never underestimate, a laser cutter of any power (even a 5W one) should be operated in an enclosure and with sufficient safety that the operator will never be exposed to the direct beam or a reflection of the beam.

Cutting bed area

A larger cutting bed will allow you to make larger work pieces, but it will also require more space for the machine. I have a 61x61 cutting bed, the machine itself is 70x80 cm and the enclosure is 1 meter x 84 cm and over a meter high. That’s quite a bit of space. But the upside from that larger cutting bed is that I have less waste (because more nesting can be done) and I can run much longer jobs in one go. All of this makes it worth it for me. But if all you do is small work then there is no point in getting a machine with a large bed. Keep in mind that you won’t be using exactly 100% of the cutting area due to hold-down, end stops, the need to ‘frame’ the work piece (to ensure that you are cutting material rather than air near the edges) and so on. Usually one axis can be completely used and one you will lose a little bit on the sides.

Air assist

For a proper cutter rather than just an engraver air assist is a must. Typically 10 to 15 liters per minute for a 20 to 40W machine. The function of the air assist is the get rid of the bits of material that the laser has already hit so that you can go deeper. The laser beam is otherwise blocked by the debris in the cut. This is a very effective mechanism and it increases the apparent power of the laser considerably. But don’t overdo it: too much air and you’ll be cooling your work piece faster than the laser can heat it up!

Accuracy

A typical laser cutter will have an accuracy of about 0.1 mm, which is for this price level ridiculously accurate. Given that you are not machining metal on a lathe or a mill and that the machines are less rigid by design more accuracy will come at a steep increase in price and you likely won’t need it anyway for the work pieces that you will want to make. The main factors in the (repeat) accuracy of the device are the way the motors drive the gantry and the head. Typically these slide freely on some kind of bearing and the movement itself is effected by a belt and a gear on the motor. Motors tend to be stepper motors, not servos so any kind of step loss will cause an immediate failure of the work piece (with servos the controller would correct for any positioning error). But because there is no back pressure from the tool this less of a problem than it would be with a milling machine. Another factor in accuracy is how square the machine is, and how level it has been set up. It pays off handily to spend some time on this and to ensure that the machine is as square as you can make it (the open frame based machines can flex quite a bit) and as level as you can make it. This will result in more accurate work and more consistent depth of cut and penetration depth across the whole of the work surface.

Cutting speed and movement speed

Cutting speed is usually limited by the laser head power, for a given job the cutting speed will simply be the highest speed at which you can still reliably penetrate the material. Movement speed is usually limited by the weight of the gantry in the Y direction and the weight of the head in the X direction. The size of the stepper motor and the stability of the power supply may come into play as well. The quality of the ways across which the gantry and the head assembly move and how much friction there is in the system will further affect the speeds.

Enclosure

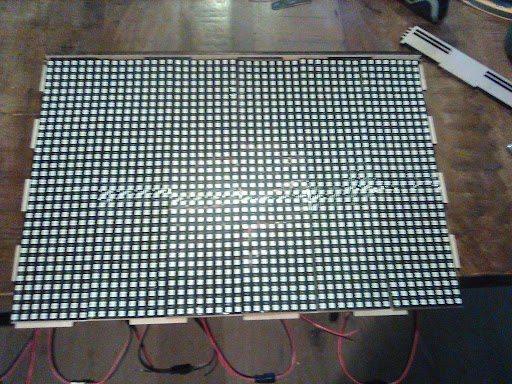

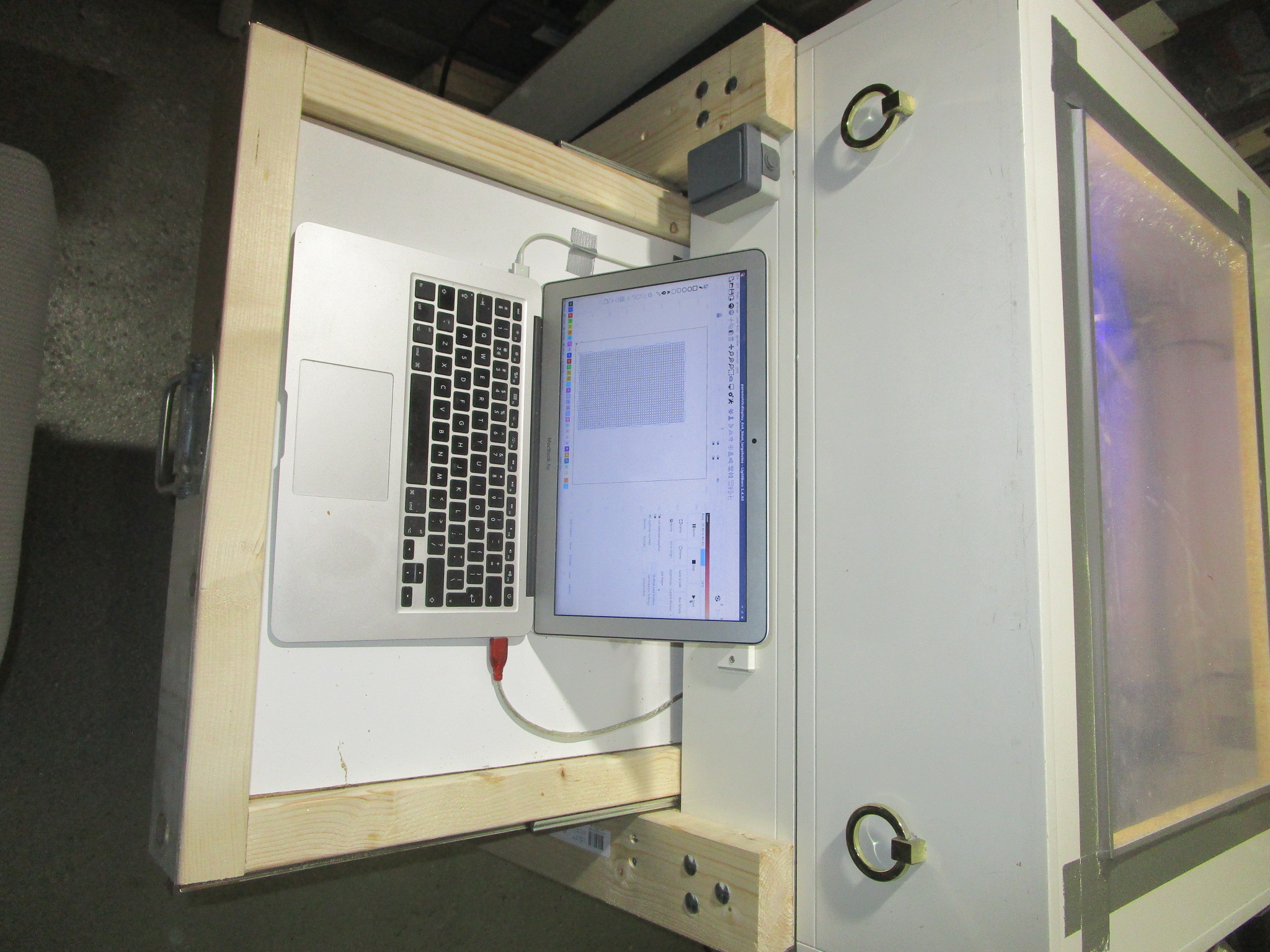

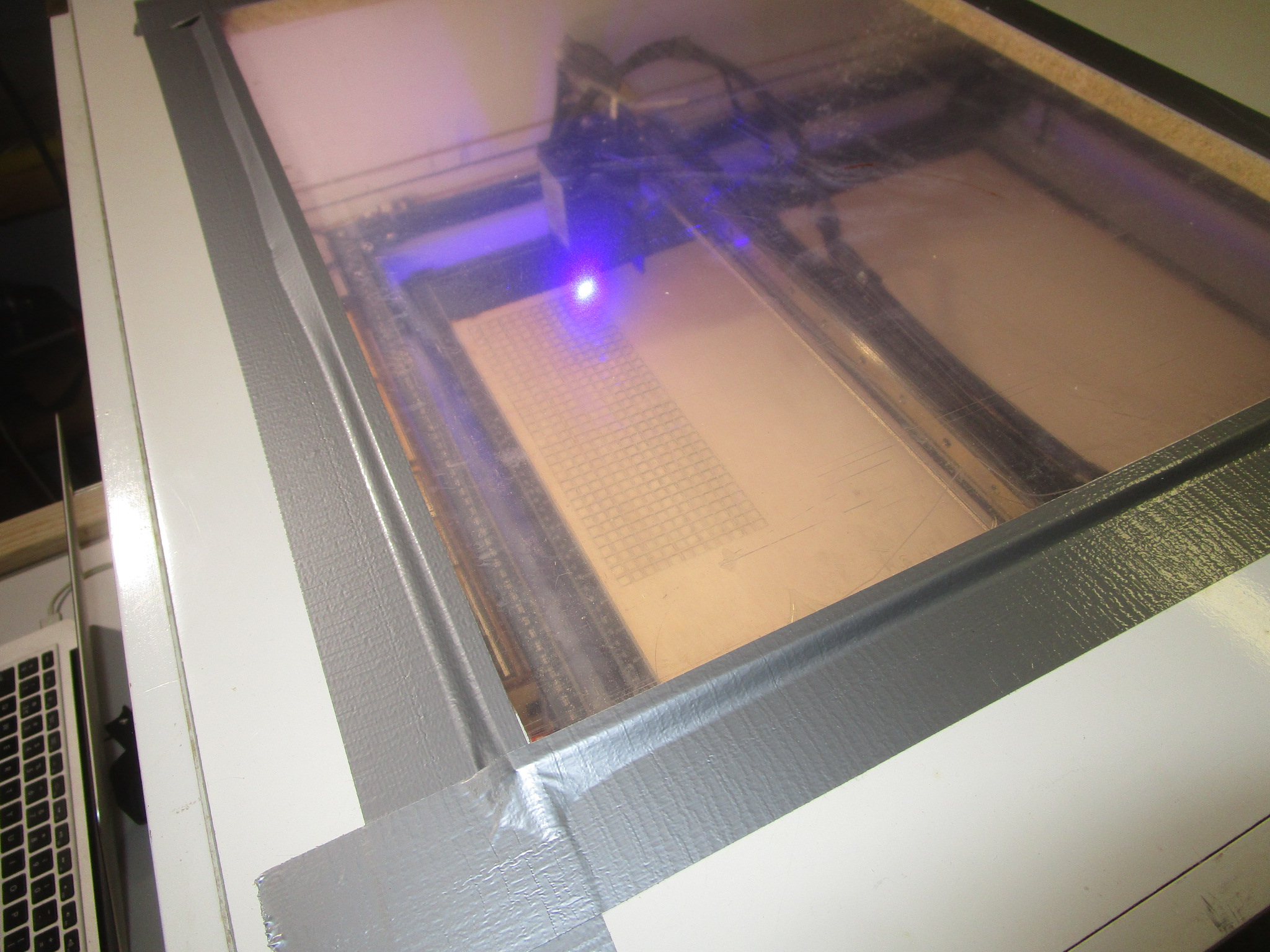

A laser cutter really needs to be enclosed, do not be fooled by manufacturers that show their machines in living areas or office like environments, it will simply not work. You will need a proper enclosure with fumes extraction and a path out of your building to use these responsibly. Here is an example, the enclosure that I built (if you look carefully you’ll see it is an old folding bed that was repurposed because I just love recycling stuff):

Type of laser

You can choose either a diode, fiber or CO2 laser depending on your needs, budget and space. CO2 lasers are the most versatile but finicky and require a lot of maintenance. Fiber lasers are ideal for cutting metal. Both of these are quite pricey and if they break the parts will be pricey as well. You can get them in very large formats and if you have the space (and the money) they may well be a good choice. Diode lasers are for the most part hobbyist and maker territory so the bulk of this document is geared towards those kinds of machines and applications.

Engraving vs cutting

Typically cutting requires more power than engraving when using the same material. Some materials can be engraved well, others not so much. As a rule, if you can cut it you probably can engrave it as well, but the reverse definitely isn’t true. Engraving is a surface treatment, so the thickness of the underlying material isn’t all that important whereas for cutting it is probably the next most important parameter besides the material itself.

How to install a laser cutter

A laser cutter must have an enclosure. Even if these are sold without using them naked is going to cause you a bunch of problems. For starters, laser cutting isn’t a very clean process. Your laser cutter will produce smoke, sometimes large quantities of it and this smoke can be extremely unhealthy to breathe in. To use a laser cutter properly your enclosure should be ventilated. A laser cutter with an ‘air assist’ (a small air pump that pushes air out parallel to the laser beam to enable it to make deeper cuts) is going to require a clean air intake to ensure it doesn’t foul up the optics. Your enclosure will need a window so you can keep an eye on what’s going on in the enclosure. And speaking of eyes, that window should block a large fraction of the laser light to make sure you keep the use of your eyes rather than that you end up finally getting that joke seen in physics labs (‘Do not stare into laser with remaining eye’).

You probably also want to invest in a pair of laser safety goggles with glass colored to match the wavelength of your laser. If you already wear glasses make sure these are sized such that they will fit over your existing glasses. A laser cutter should be set carefully level and any kind of support needs to be square and warp free. Inside the perimeter of the laser cutter you will need a sacrificial bed or a bed that the cutter can’t cut to support the material that you intend to cut. This so that the air has a place to go to and so that you don’t end up cutting whatever supports your material. Because laser cutters can generate a lot of localized heat (that’s what they’re made for!) there is some non-zero chance of setting your work piece on fire. So a laser cutter should never be operated unattended, and you should have some means of putting an actual fire on the bed of your machine out. The surface below the laser work area should be fire proof.

You will need an easy to access e-stop in case there is a fire or other mishap (it will cost you a work piece but that’s a small price compared to burning down your house or garage). You can use one of those big red mushroom switches that stay in position after you’ve pressed them to de-energize the system or you could use a multi-outlet bar with a switch. Never ever cut PVC, the fumes that it produces are extremely toxic and it will corrode your machine and/or injure or kill you. Chlorine gas is super dangerous and cutting PVC with a laser will produce it in quantities large enough to be a real problem.

Driving the laser

Most lasers talk to their host computers (you’ll need one of those too) using a serial-over-USB protocol, and the language they speak is called G-Code, which is a venerable but highly effective way to control various machinery by computer. G-Code is universal and used to control anything from lathes and mills to laser cutters, coordinate drills and pretty much anything else used in manufacturing these days. But programming G-Code directly is somewhat tedious, especially if you change your design frequently so the usual pathway is that you have some piece of software to create the design and then a piece of software to take that design (in some intermediary format) and to convert it to G-code. Consumer targeted software packages that are relatively easy to use and feature rich are:

- LightBurn, https://lightburnsoftware.com/ , LightBurn is a great piece of software, kudos to the makers for supporting Linux even though that is only a fraction of their market. It works quite well as long as you stick to the supported Linux versions, just dedicate an old laptop to your Lasercutter and you’ll be fine. LightBurn supports a camera that you can position over the bed of the cutter to keep you informed about what’s happening inside the enclosure. If you run into trouble with support for your camera you may use ffmpeg to convert the camera’s format to one that LightBurn can handle like so: ‘ffmpeg -i /dev/video4 -map 0:v -vf format=yuv420p -f v4l2 /dev/video6’ where /dev/video4 should be your real camera and /dev/video6 v4l loopback device (created using ‘sudo modprobe v4l2loopback’). I really should do a separate article on working with LightBurn. It is one of very few pieces of closed source software that I use and was very happy to pay for.

- LaserGRBL, https://lasergrbl.com/

- OpenBuilds, https://software.openbuilds.com/

- LaserWeb, https://laserweb.yurl.ch/

- lots of others, if I’ve missed your software please send me a name and a link to include

Some of these are free, some are commercial software, in the end all of them will work but the convenience level may vary and some may work better (or worse) for your particular setup and material. Try before you buy, make good use of the trial period and cut as many different materials and thicknesses as you can to get a good feel for the software before you decide. Pay special attention to how the software fits into your workflow, whether the file formats that you intend to use are supported without conversion steps and that the import of those files is error free.

The laser driver software that I’ve seen all still misses tricks of the trade and more than once I’ve seen (subtle) bugs. For instance, radius compensation (to offset the path half the beam width so you get more accurate work) needs to be done to the outside for outer curves and for the inside for inner curves but the software tends to get confused by what is outer and what is inner especially if the tool path changes direction. This is the result of a naive implementation of the correction, the right way to do it is to first figure out if a curve is inner or outer and then to offset in the direction of the scrap. But that implies that you know what the scrap is and that information isn’t necessarily present in the input file to the laser so the software has to make an educated guess. And this doesn’t always work. Other bugs I’ve seen relate to penetrating thick material. In order to do that you normally start well in the scrap and then spiral into the edge of the work piece so the laser is always in motion when it hits the work piece itself. Constant beam power (so that you always cut with the same amount of power) is another fact that you really would need to offset for, especially if the spot size is asymmetrical, so you need to cut slower in the direction where the beam is less focused for consistent results. All of this is tricky to get right and some of the software out there is better at these things than others, but nothing on the market today gets all of these factors right.

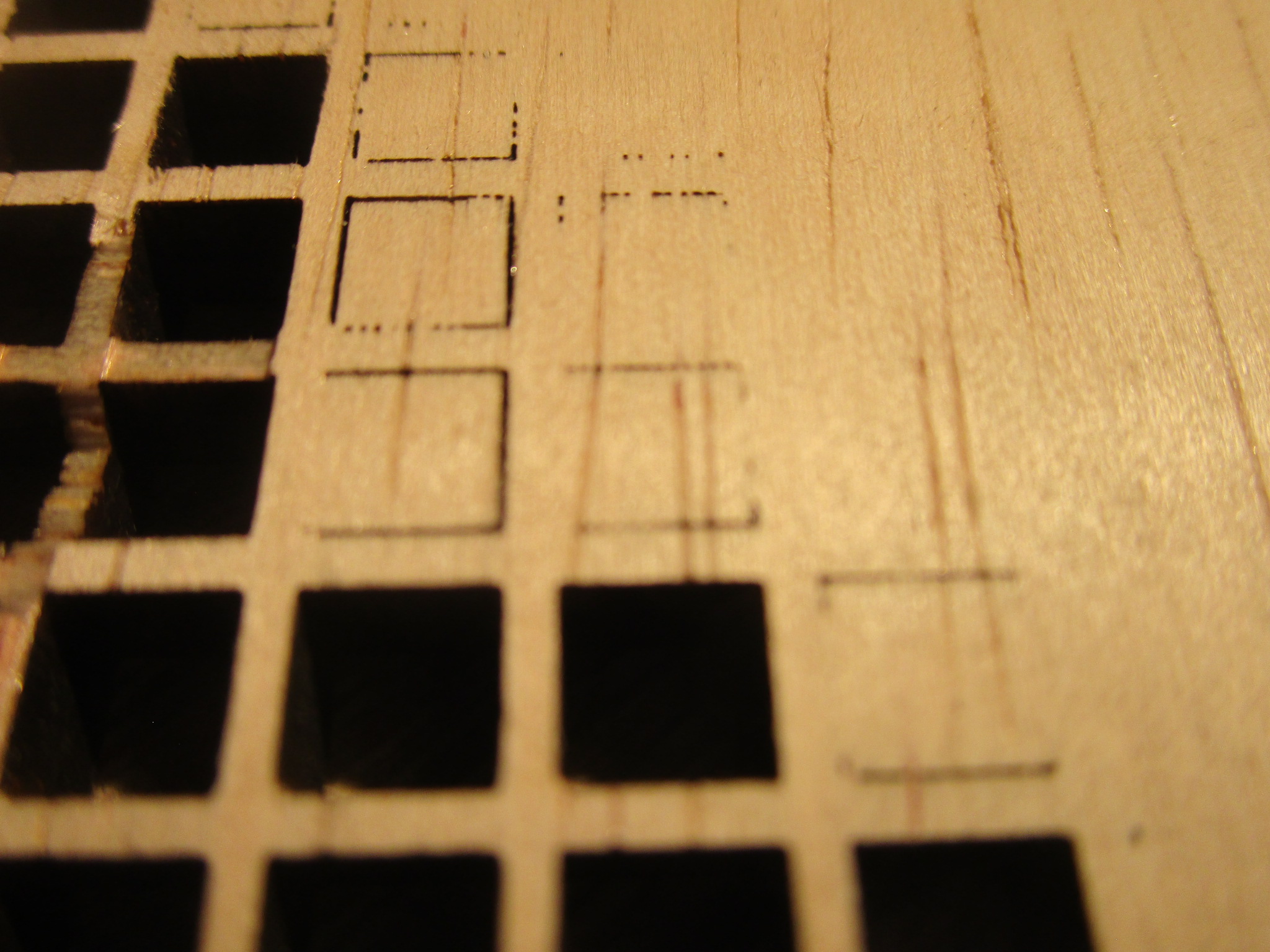

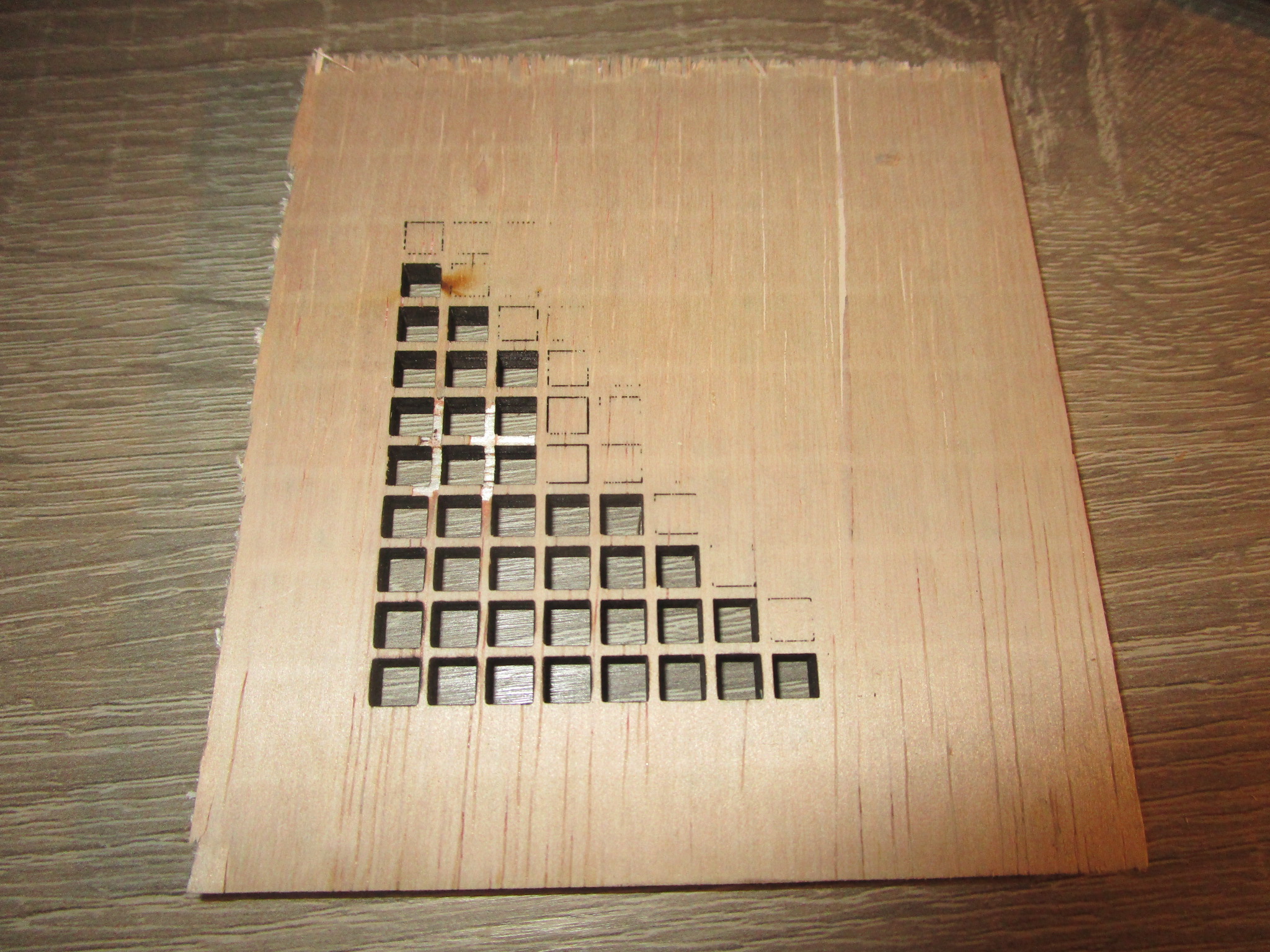

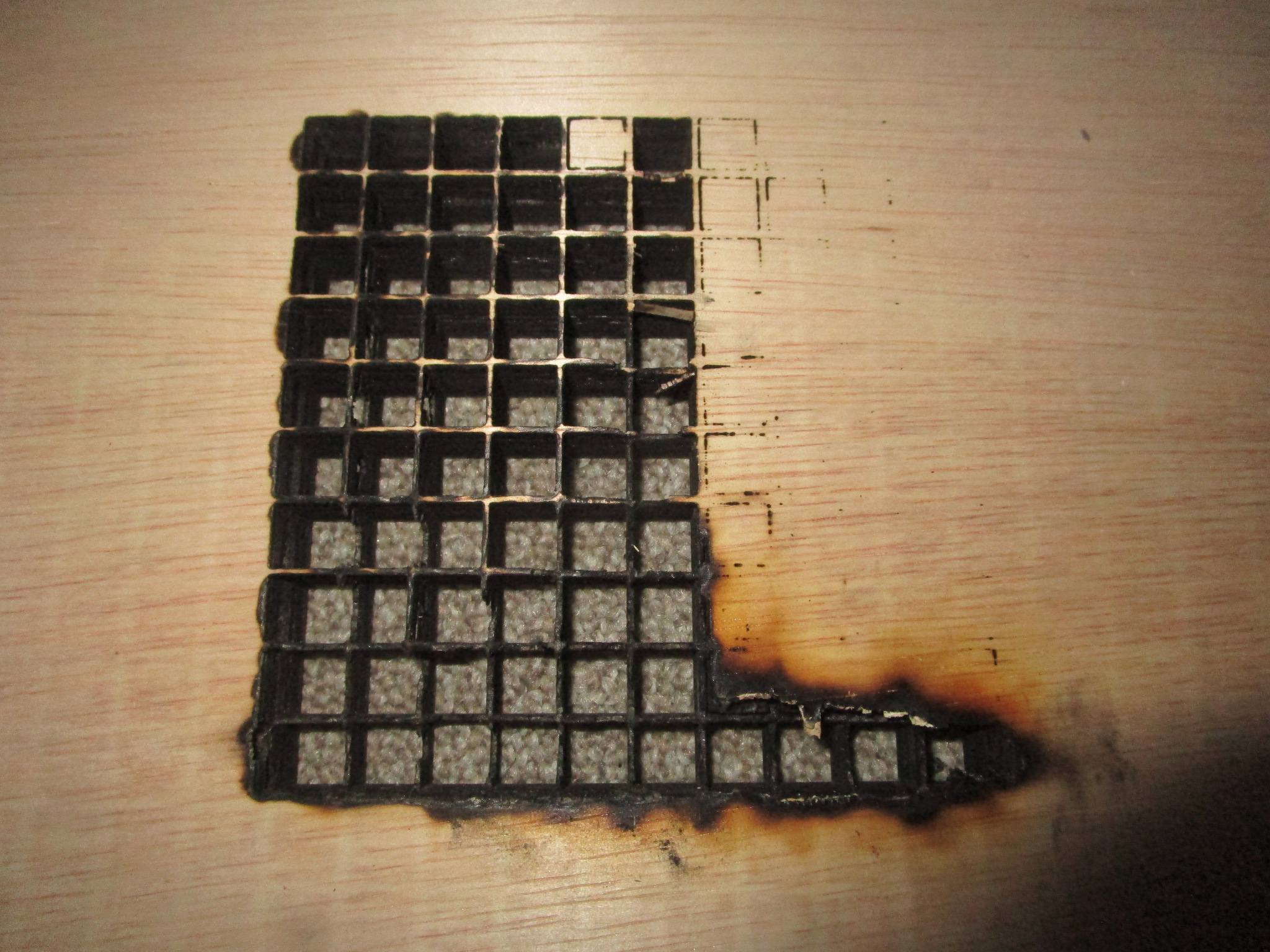

In this extreme close-up of the back of a piece of birch plywood you can see the effect of an asymmetrical spot, the machine clearly favors cutting in the ‘X’ direction because that’s the orientation of the lasers in the head which results in a beam that is slightly wider than tall. In the ‘Y’ direction that causes some of the beam to spill over onto the side of the cut. So you will need to go slower in one direction than the other, but because most software can’t do that what you end up doing is to slow down to the lowest speed that will still penetrate the work piece in all directions of travel. This will result in a slower cutting speed and some loss of accuracy in one dimension. Knowing your cutter intimately will help to identify and correct such issues:

Making the design

To cut any kind of material at all you first need a design. You can make your own designs, you can buy designs made by others and you can adapt designs and artwork that wasn’t necessarily intended for laser cutting or engraving using software. There are also free laser cutter design generators that will generate a bespoke pattern for you on the fly. Software used for the design phase is quite varied, on the one hand there are parametric tools that are closer to programming environments than design software, on the other hand there are fully interactive drawing programs, CAD software, photo manipulation software etc. Depending on your skill level and goals you will select the package most appropriate for your needs. If you are more of an artist than a technology person you will likely gravitate to drawing programs and if you are an engineer you will probably feel most at home with a CAD program. If you’re a programmer then parametric design software may be the thing for you. In each of these categories there are multiple contenders.

The list of subjects of things that you can make is pretty much endless, but things that I keep coming across are all manner of boxes, jigs for other tools, decorative pieces and functional machinery. The longer I work with the laser the more ways I find myself using it.

- Interactive CAD Software

- Tinkercad

- Rhino

- Blender (less suitable in my opinion)

- AutoCad

- Sketchup

- Drawing programs

- Gimp

- Inkscape

- PhotoShop

- Illustrator

- Parametric CAD

For each of these there will be ways to arrive at the two-dimensional intermediary file that will be used by the laser driver software to be converted into G-Code. Common file formats in use for cutting are SVG, DXF and JPG. Usually the software will support quite a few more of these, it is crucial that whatever format the design software exports can be imported into the the laser driver software.

More resources for designs:

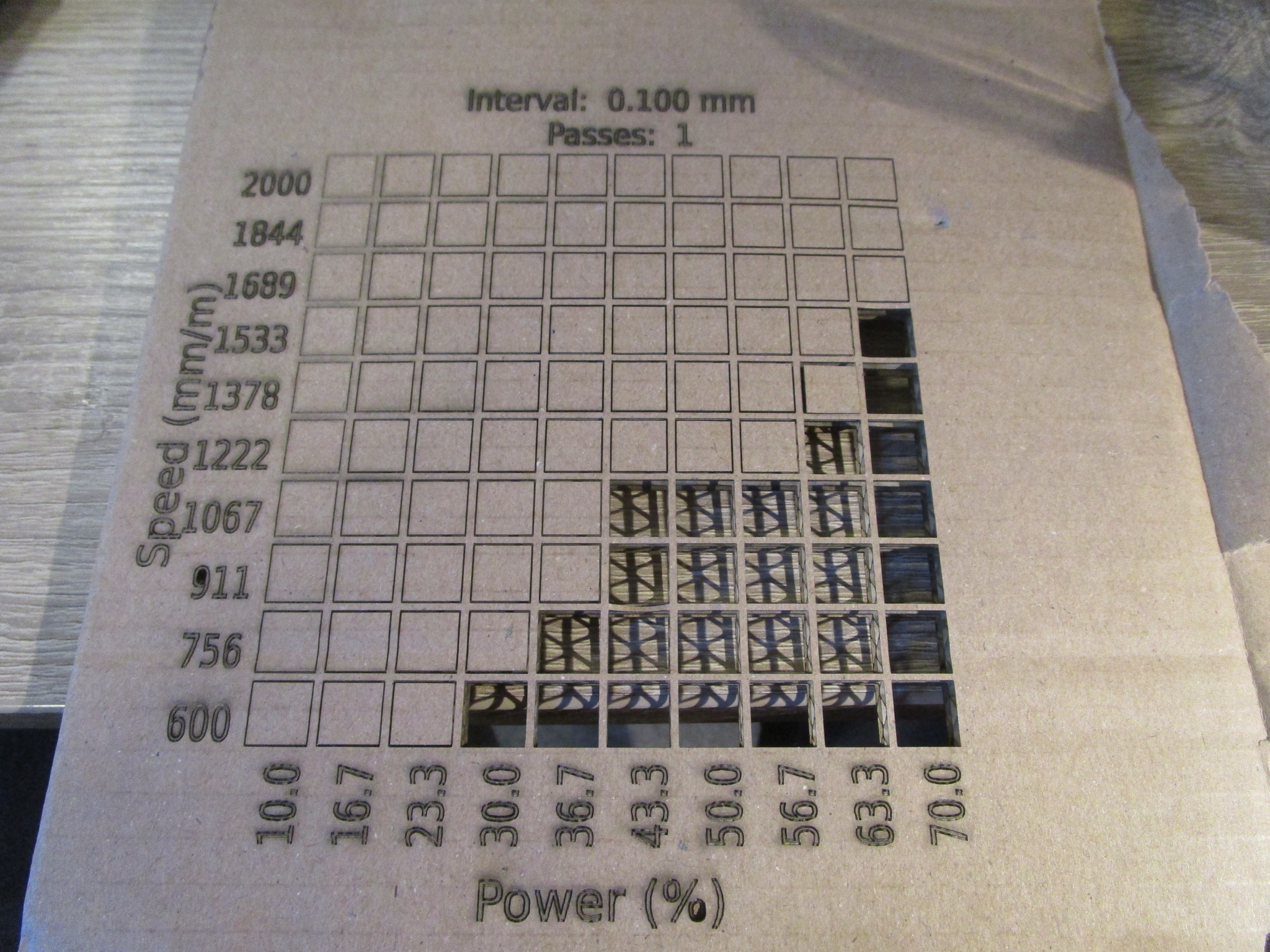

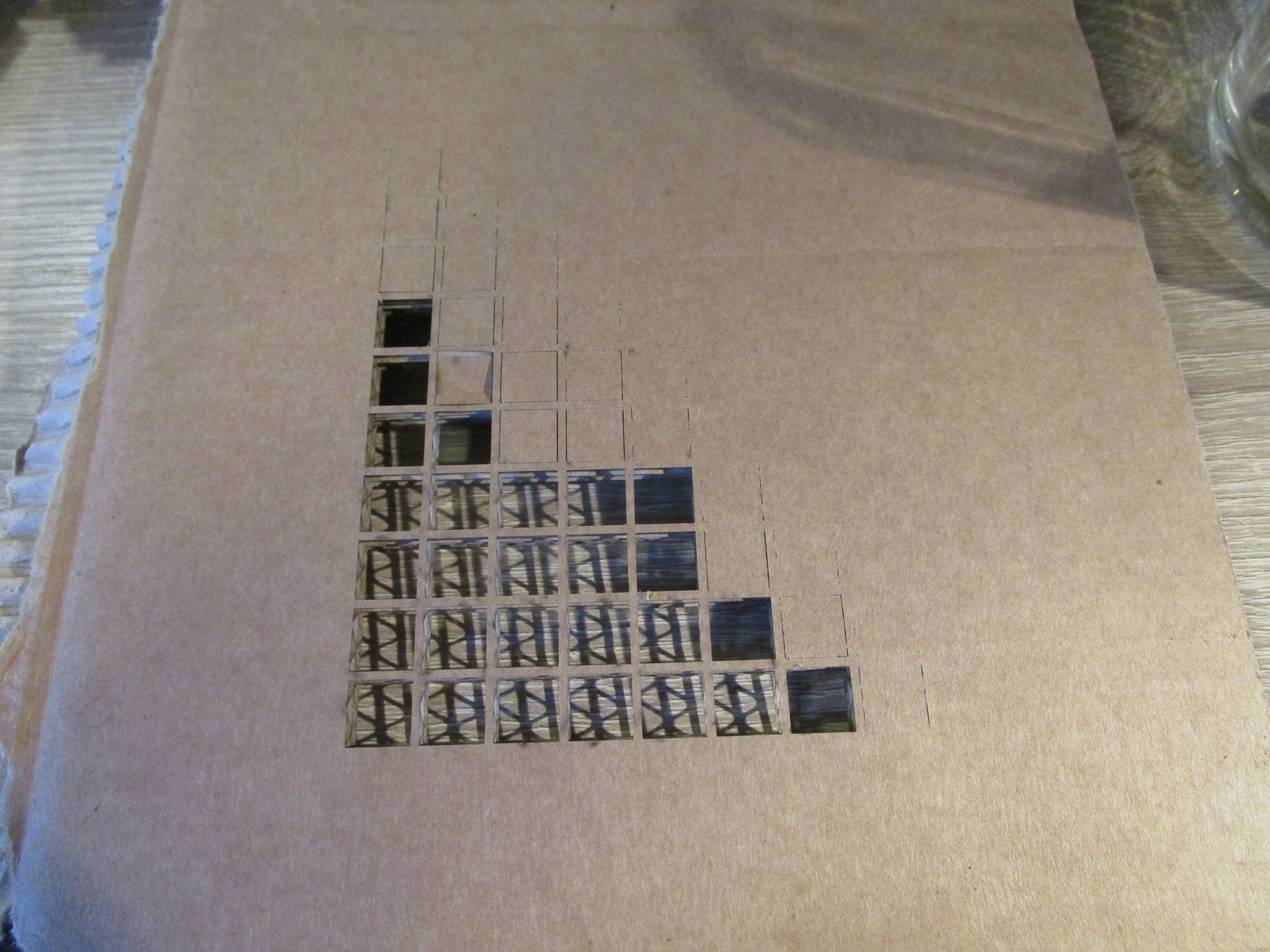

Materials

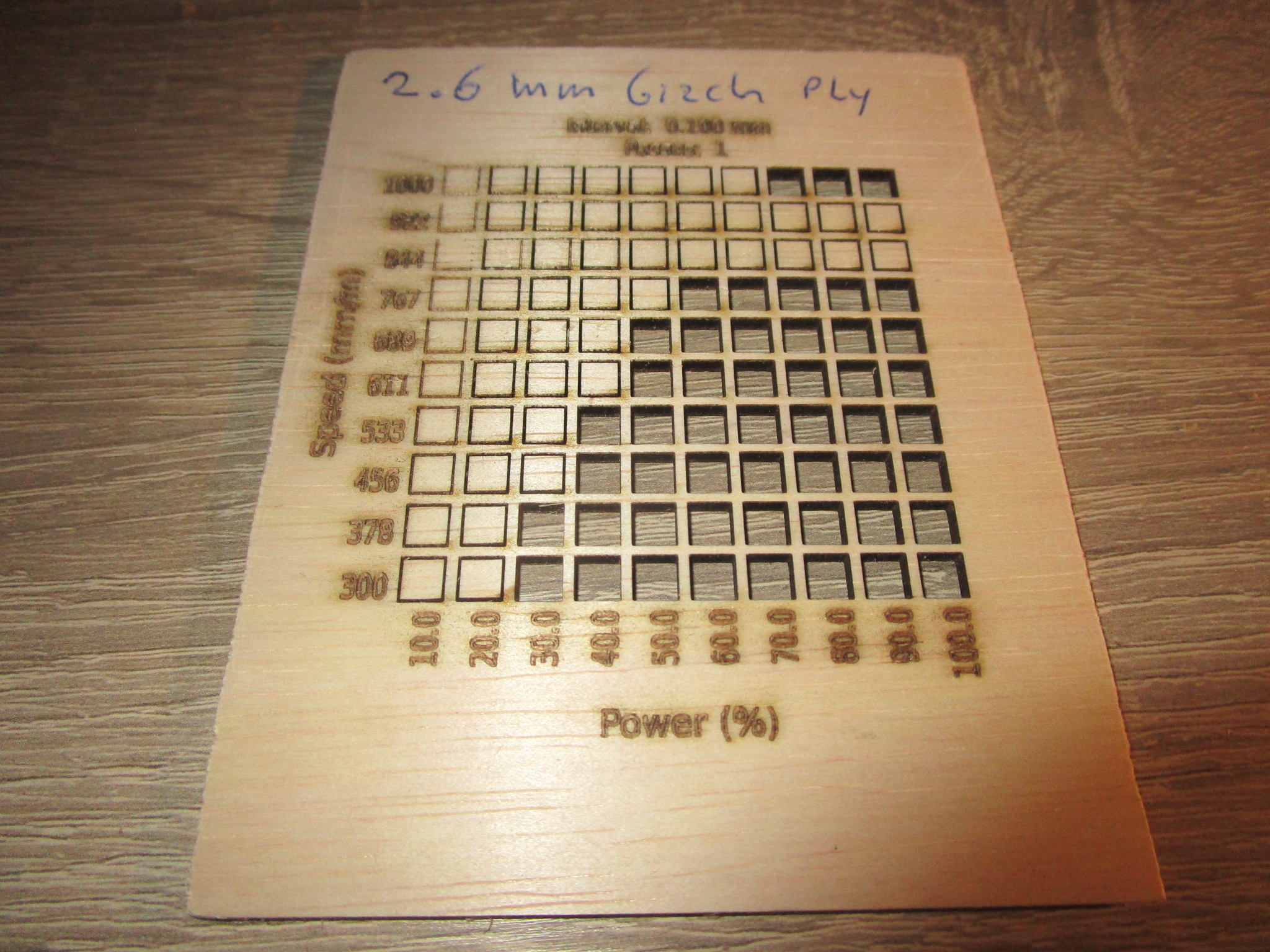

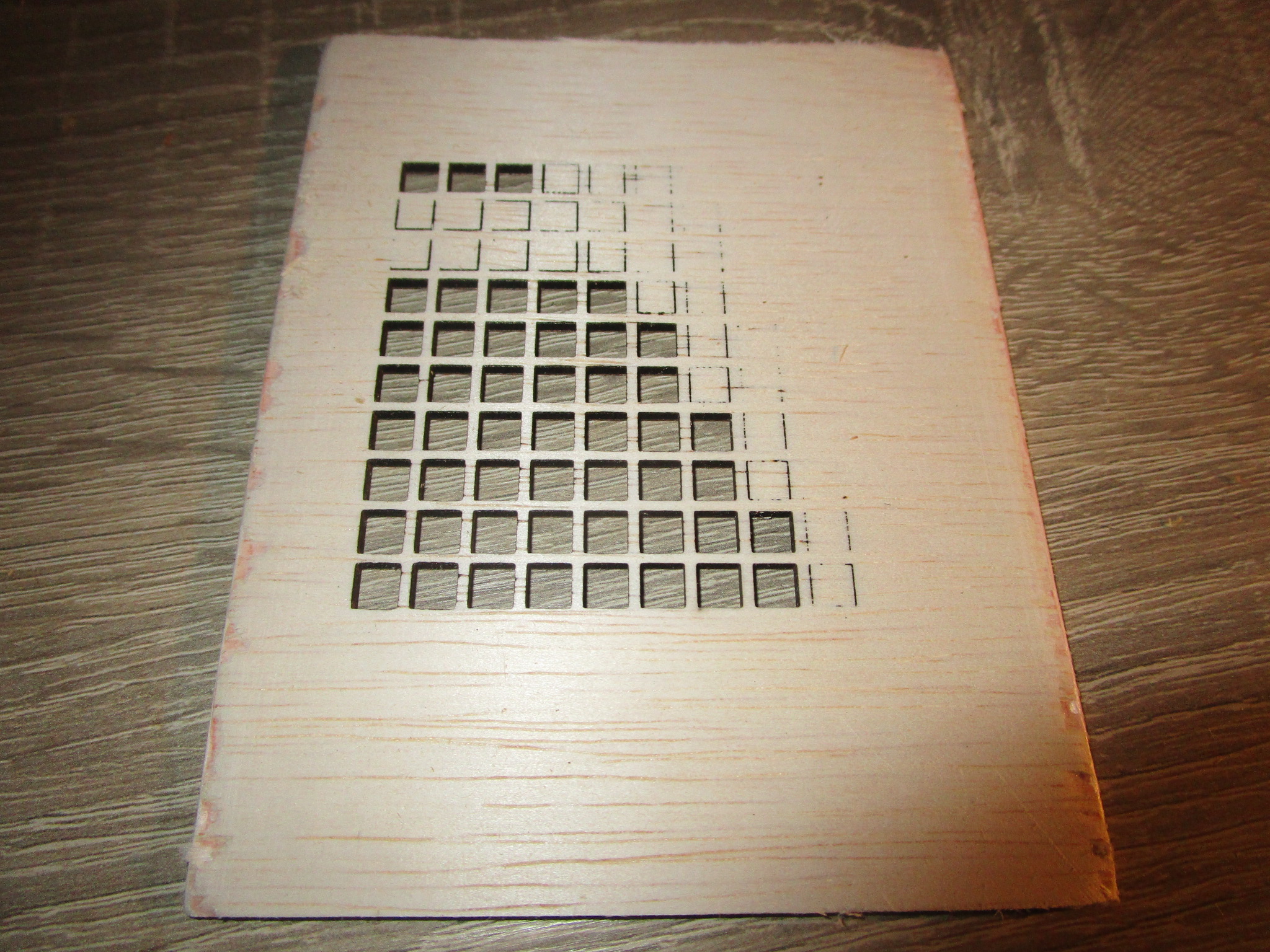

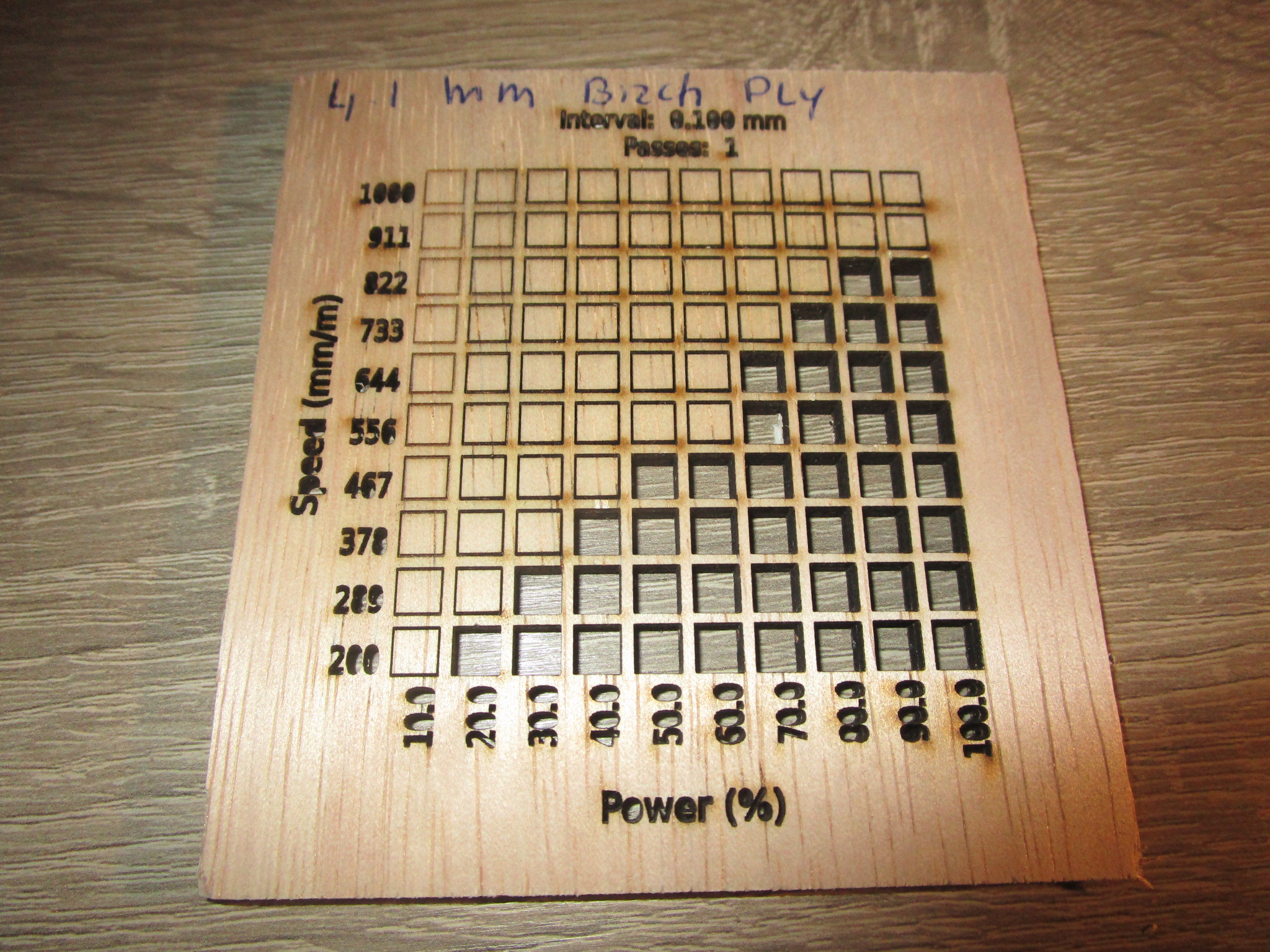

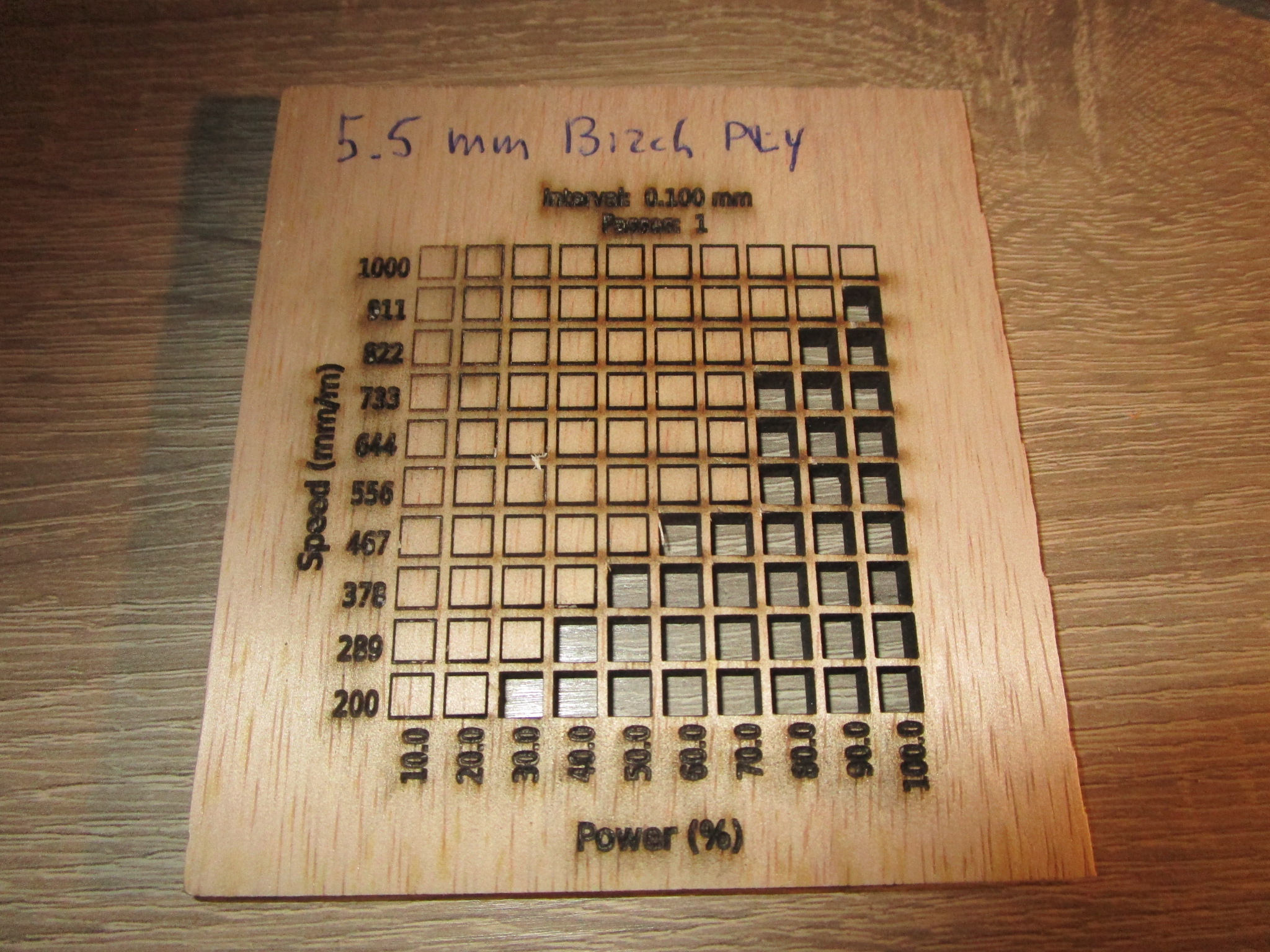

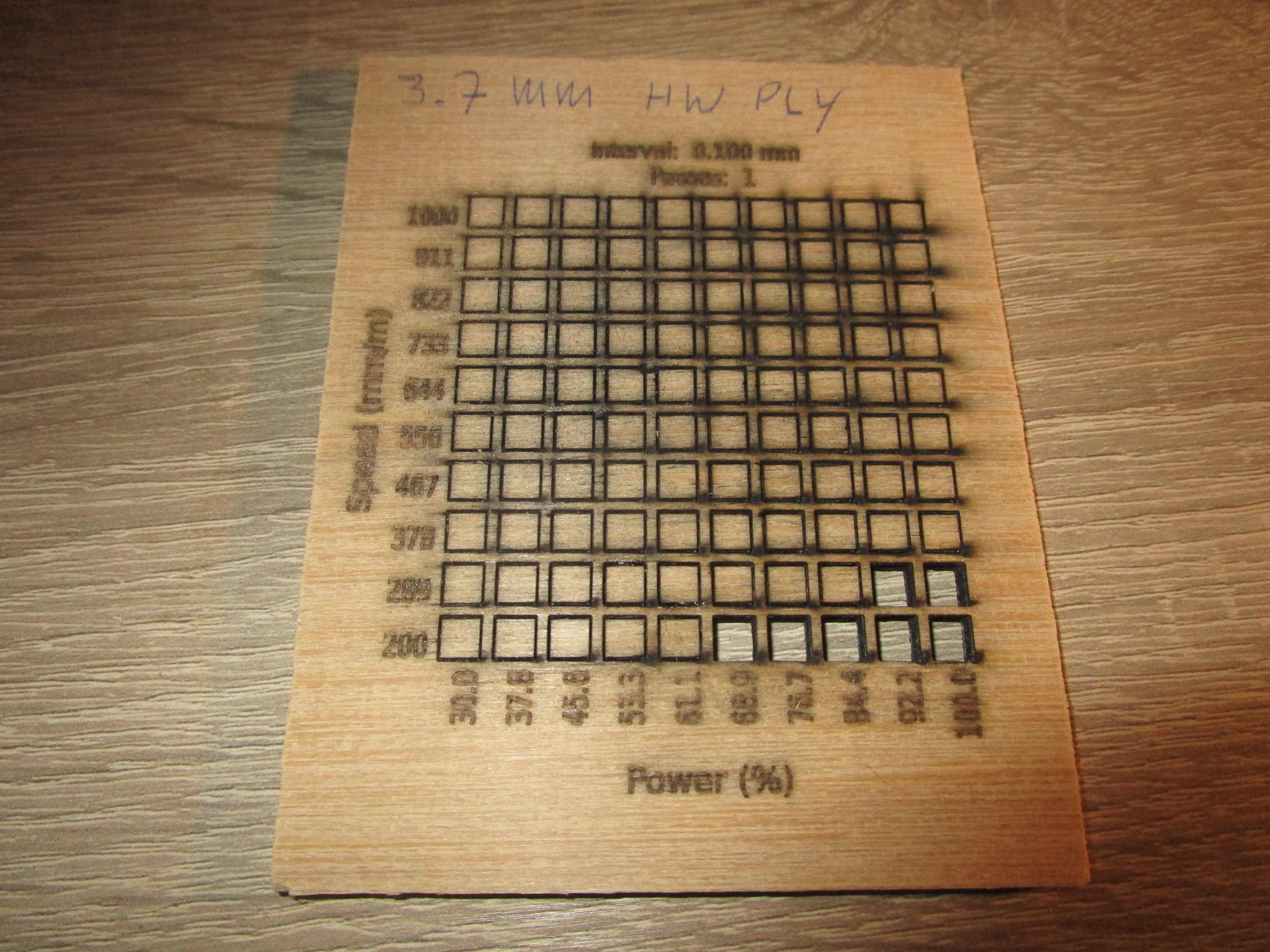

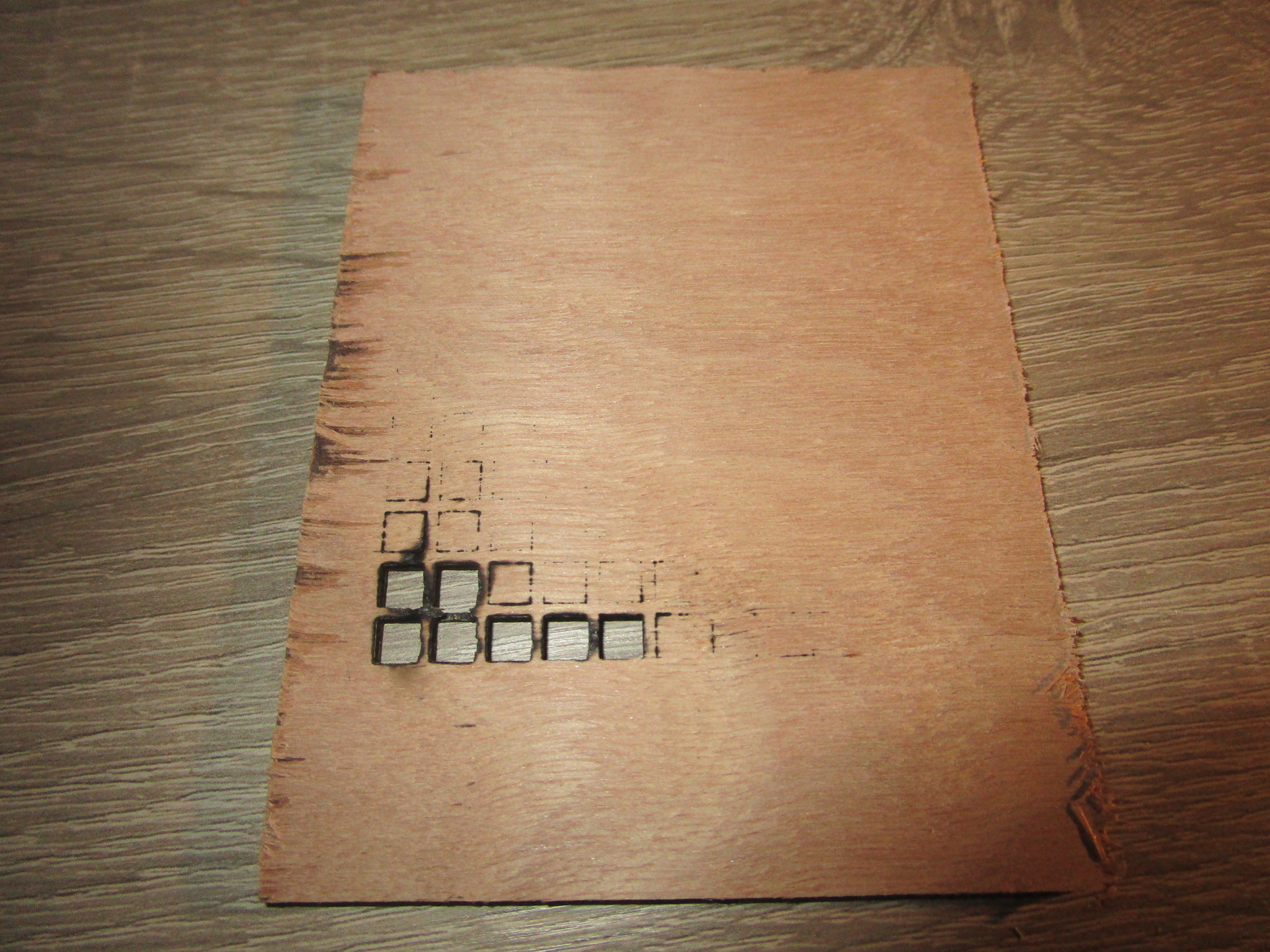

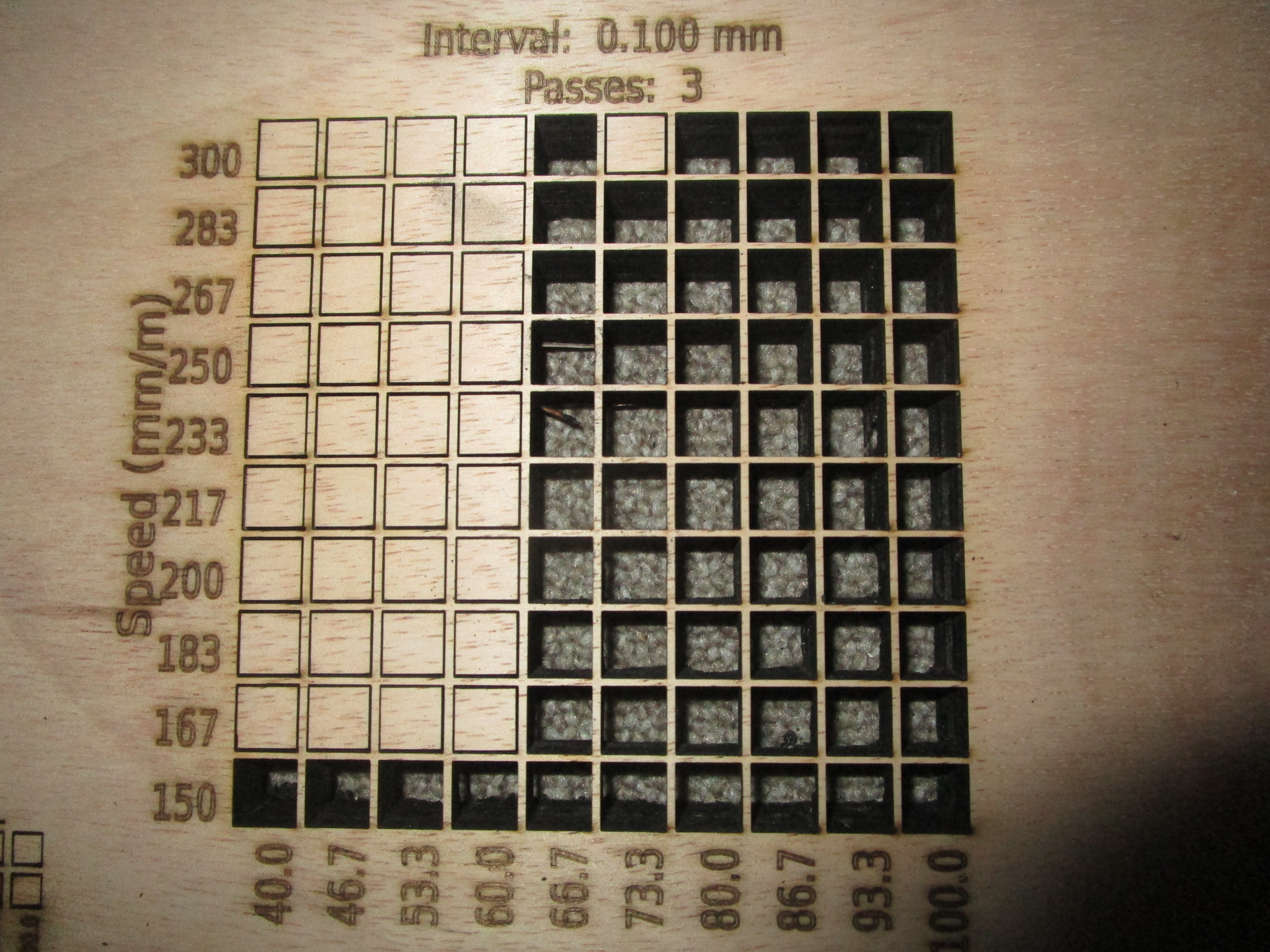

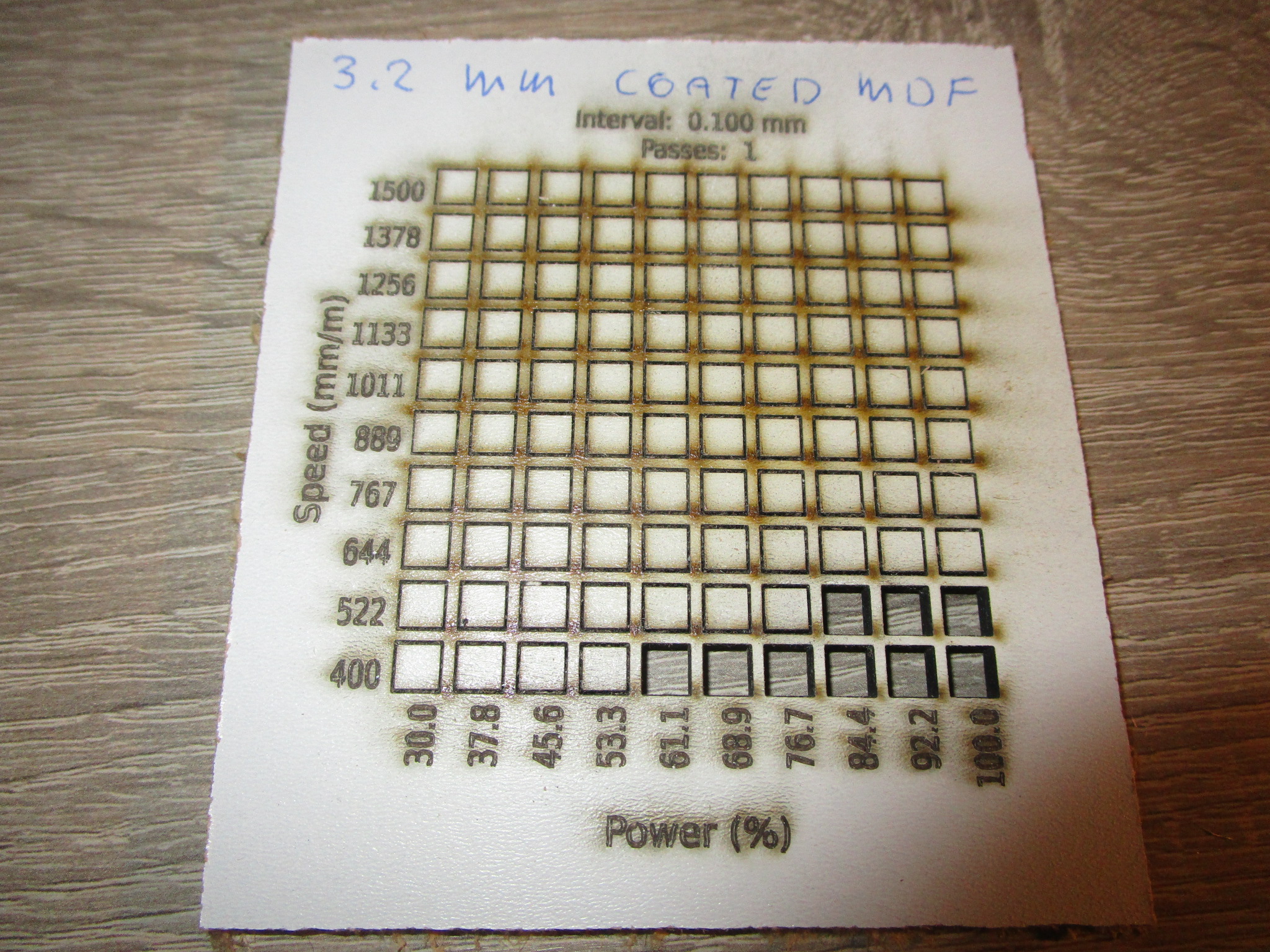

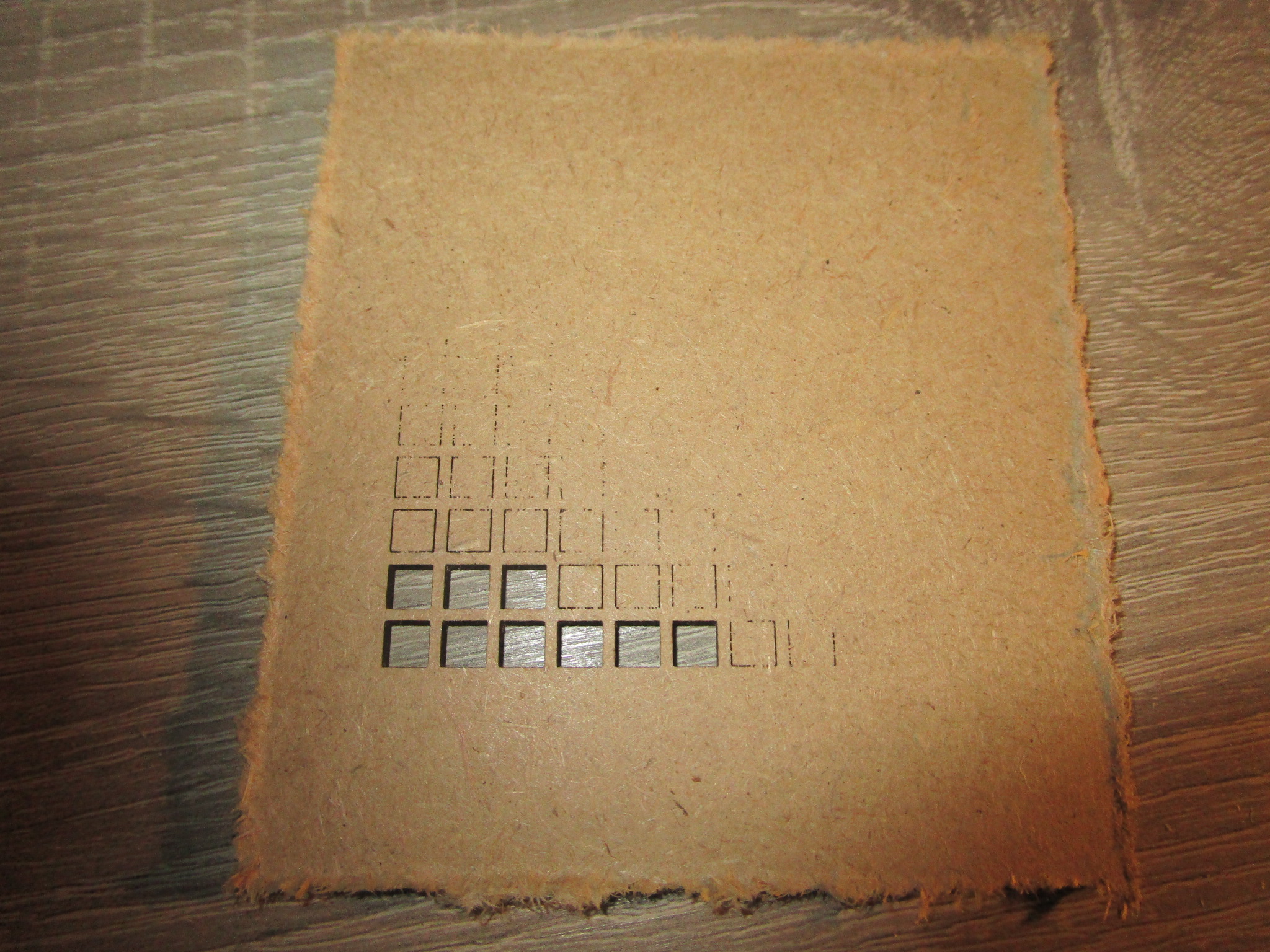

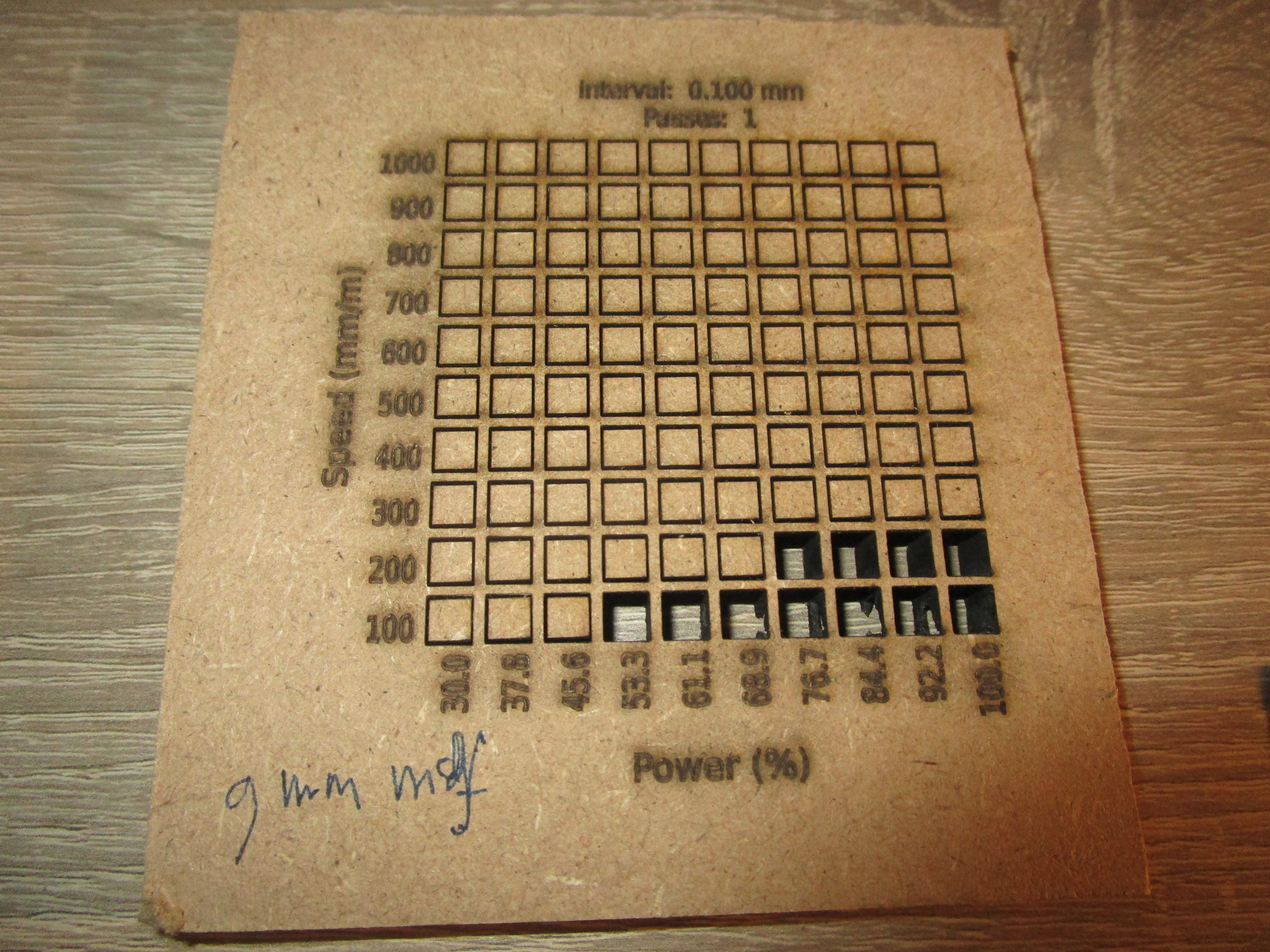

You can cut/engrave a wide variety of materials with results ranging from ‘excellent’ to ‘unusable’ depending on the power of your machine, the speed of the movement of the laser, the state of the optics (clean, undamaged) and the state of the material. I intended to create a catalogue of machines, materials, cutting speeds and power levels here to save everybody the trouble of having to re-run these for normal conditions. In case of troubleshooting or exceptional conditions you may still want to create a materials test. I use ‘LightBurn’, so those are the materials test coupons shown here but most laser driver software will support a similar feature.

I will add photographs of front and back of all materials tests to save you some work.

Note that not all materials are safe to cut with a laser (I’ve added details for those materials that I’m aware of) and not all materials can be cut with a laser. Some materials will give off toxic fumes. These can cause respiratory issues, eye issues, major injury or in an extreme case death. Do not cut materials that you are not 100% sure are safe to cut and don’t try anything new without first consulting the material safety data sheet and at a minimum your friendly local search engine to determine whether or not it is worth trying at all.

If you want me to try a particular material either send me a sample or send me a photograph of front and back of your own materials test (see below for what those look like).

Wood

Wood is an excellent choice for material to be cut. A moderately powered laser cutter will be able to cut through several millimeters of material with relative ease, usually the limiting factor is the cutting speed, a less powerful laser will go slower (and has a higher chance of scorching the material). Diode lasers will happily cut softwoods even at impressive thickness but struggle with hardwoods. Hardwoods are more dense than softwoods so the laser needs more power to do the same job and that power isn’t always available. Also, because more power (or lower speeds) are needed charring can get excessive (or even outright burning). Careful balance in power and speed and sometimes increased numbers of passes can get the job done and there are some tricks of the trade to do the seemingly impossible. Engineered wood is hit-and-miss, you’ll also have to deal with the fumes in a more responsible way because besides carbon from vaporizing wood you’ll also be vaporizing some glue and this can produce some pretty nasty stuff.

If you don’t like the dark edge that laser cutting gives the wood consider oversizing the sides of the work piece by 0.1 mm or so and sanding off the excess. It’s an extra step but the difference in looks may well be worth it. Cut wood can smell burnt for a long time. You can reduce this smell by sanding off the edge, by lacquering or painting the piece or by sandblasting it (lightly, wood abrades very quickly). Lacquer and paint don’t adhere very well to the burned edge because some of it is loose material, that’s also why these particles make it into the air. It is essentially the same as a very thin smoke because of the air movements liberating particles from the workpiece. That’s also why eventually the smell fades (but this can take a long time, up to months).

If you’re going to cut plywood, be aware that not all plywood is created equal and that some is put together with glues that give off bad vapors, if there is a thin black line between the plys that means you probably have plywood with ‘phenolic resin’. It may also result in being harder to cut.

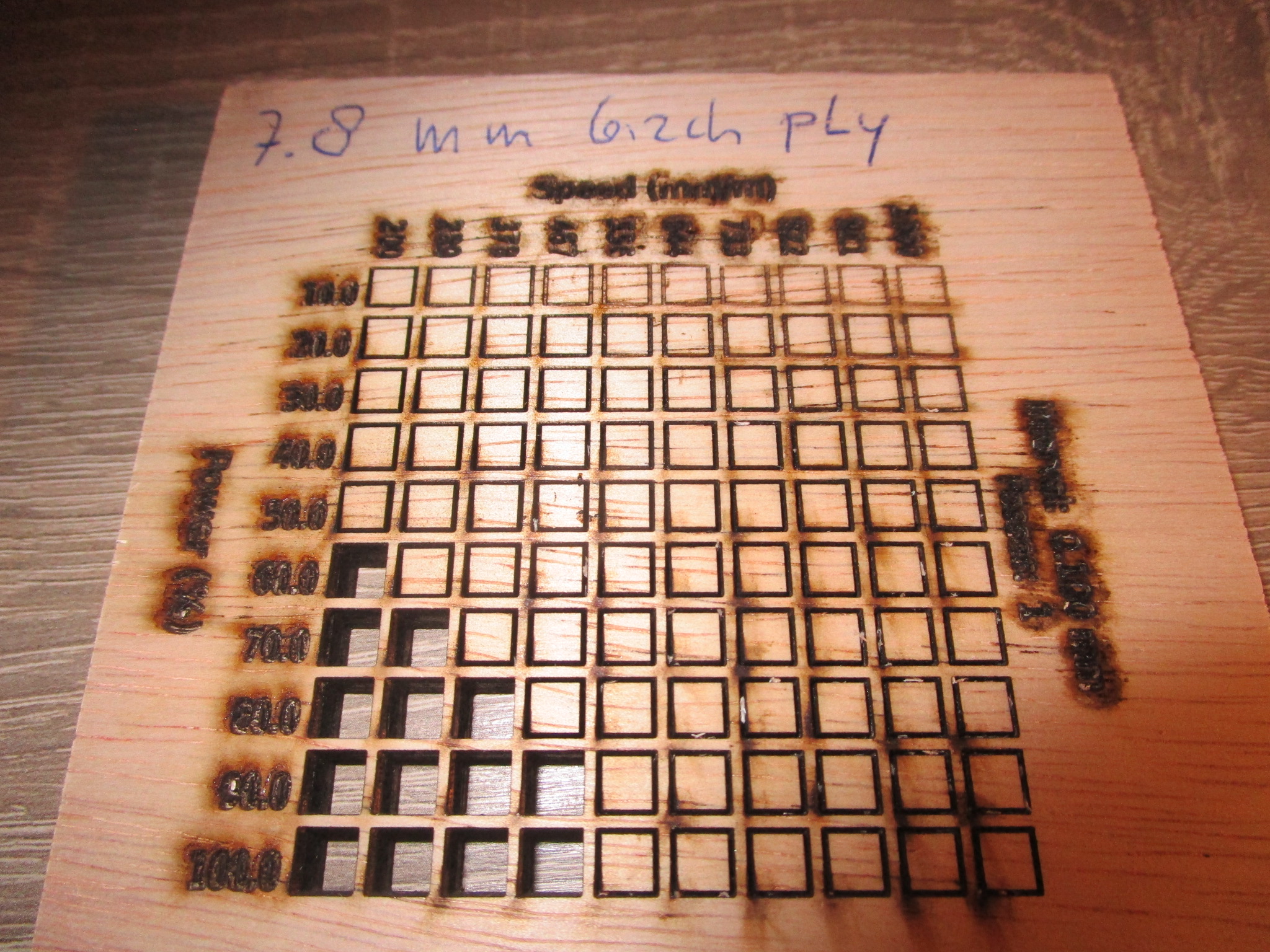

Based on quite a large number of material tests here are the results (nominally 30W cutter, clean optics, air assist on):

- Birch plywood

- 2.6 mm, 60% power, 700 mm/minute, single pass (for more speed: 100% power, 1000 mm/minute, less laser life though)

- 4.1 mm/5.5 mm, 60% power, 450 mm/minute, single pass (for more speed: 100% power, 800 mm/minute)

- 7.8 mm, 60% power, 200 mm/minute, single pass (for more speed: 100% power, 400 mm/minute)

- 11.8 mm, 60% power, 150 mm/minute, single pass (for more speed: 100% power, 250 mm/minute)

- 18 mm, 80% power, 300 mm/minute, three passes

- MDF

- 3.2 mm coated, 80% power, 500 mm/minute, single pass (more power doesn’t seem to help)

- 9 mm, 80% power, 200 mm/minute, single pass (more power doesn’t seem to help)

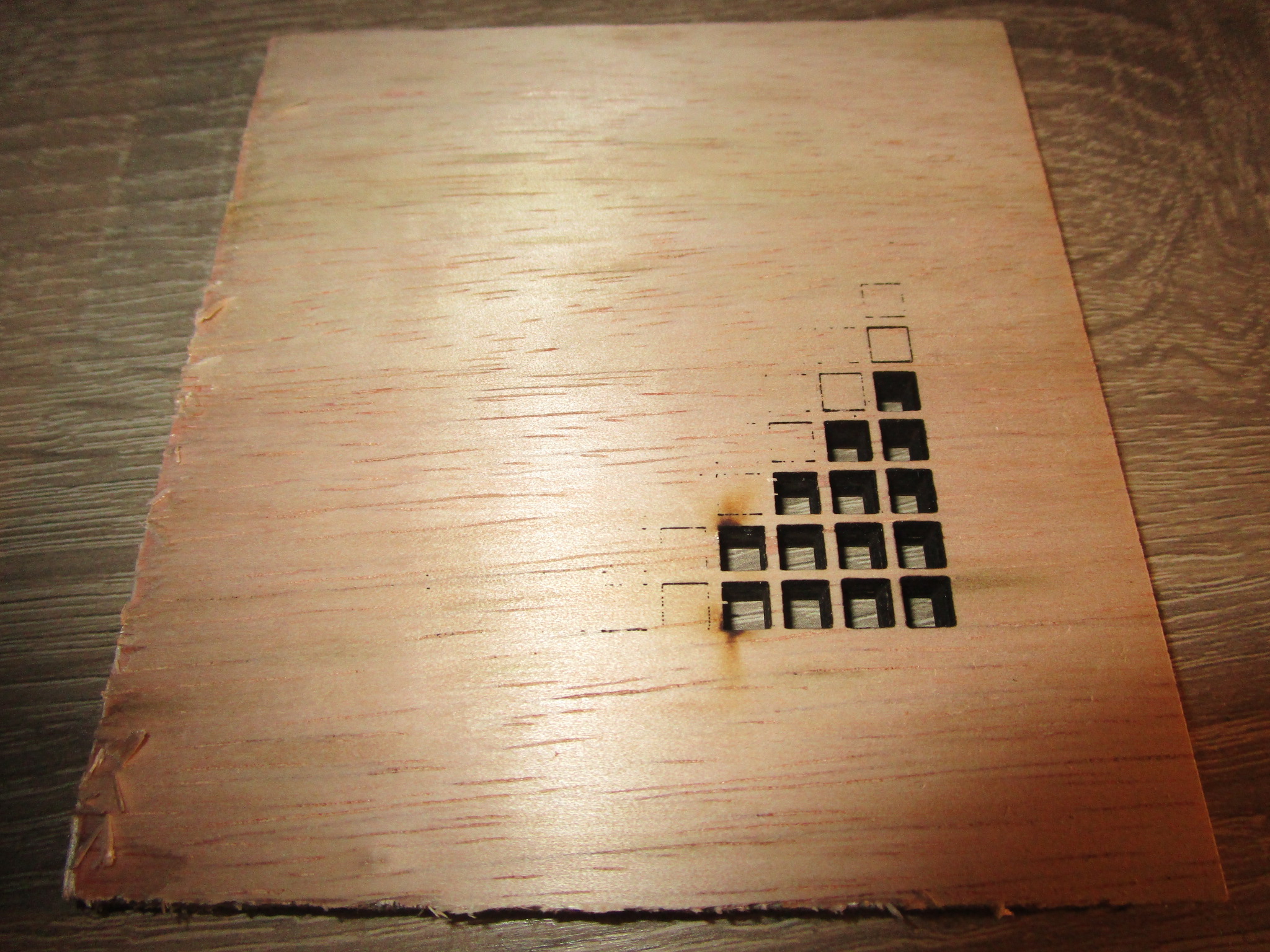

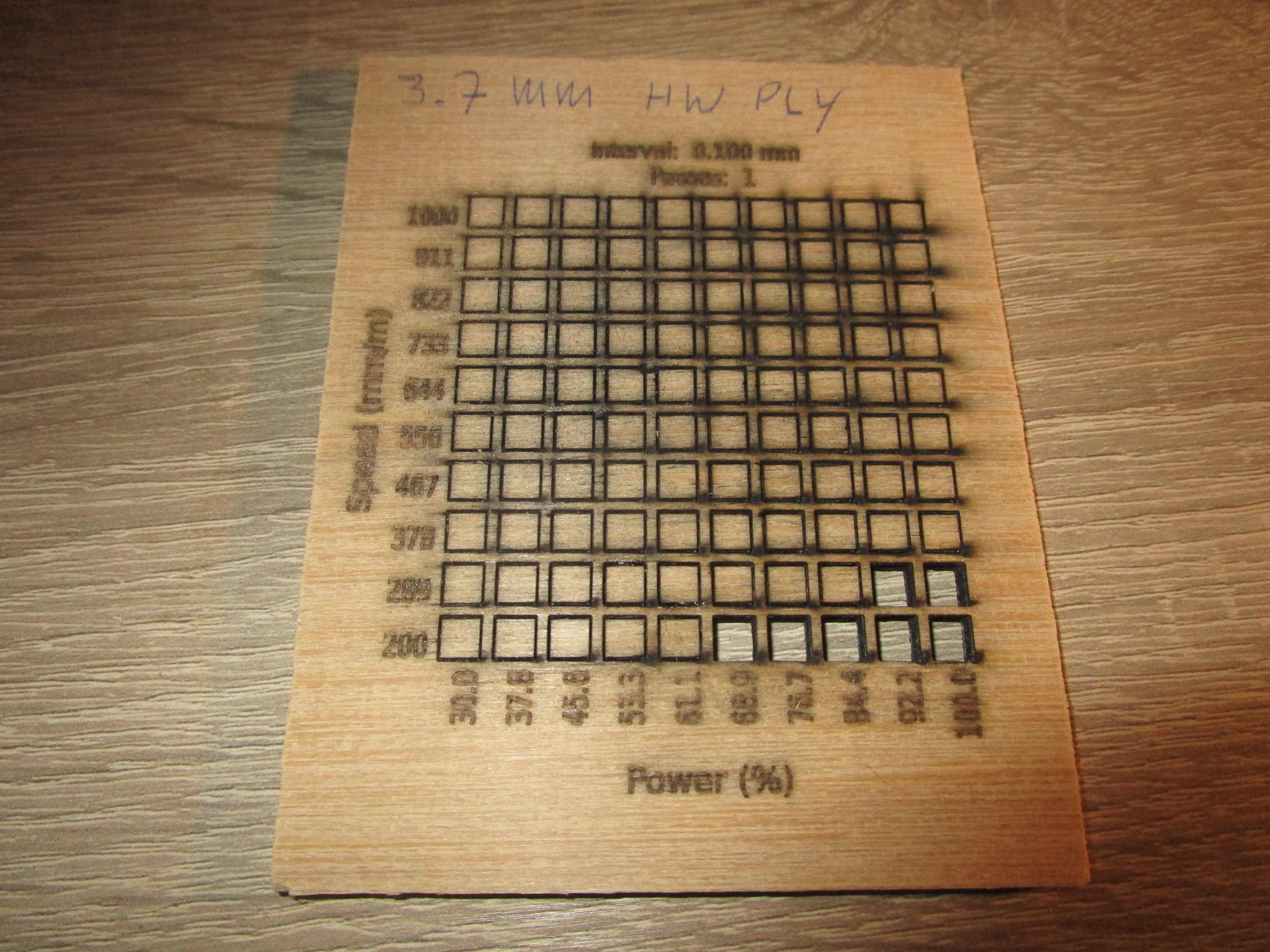

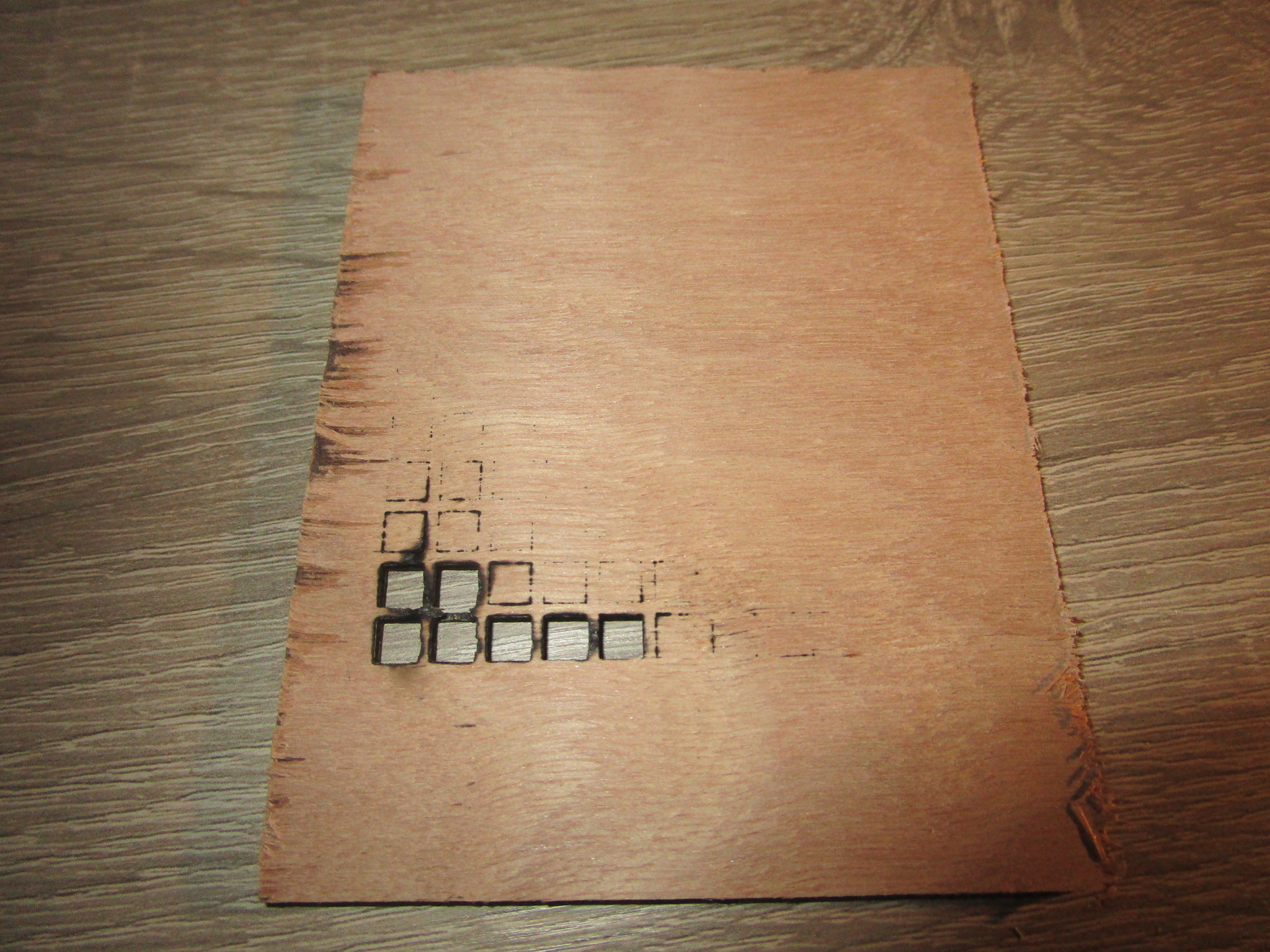

- Hardwood ply

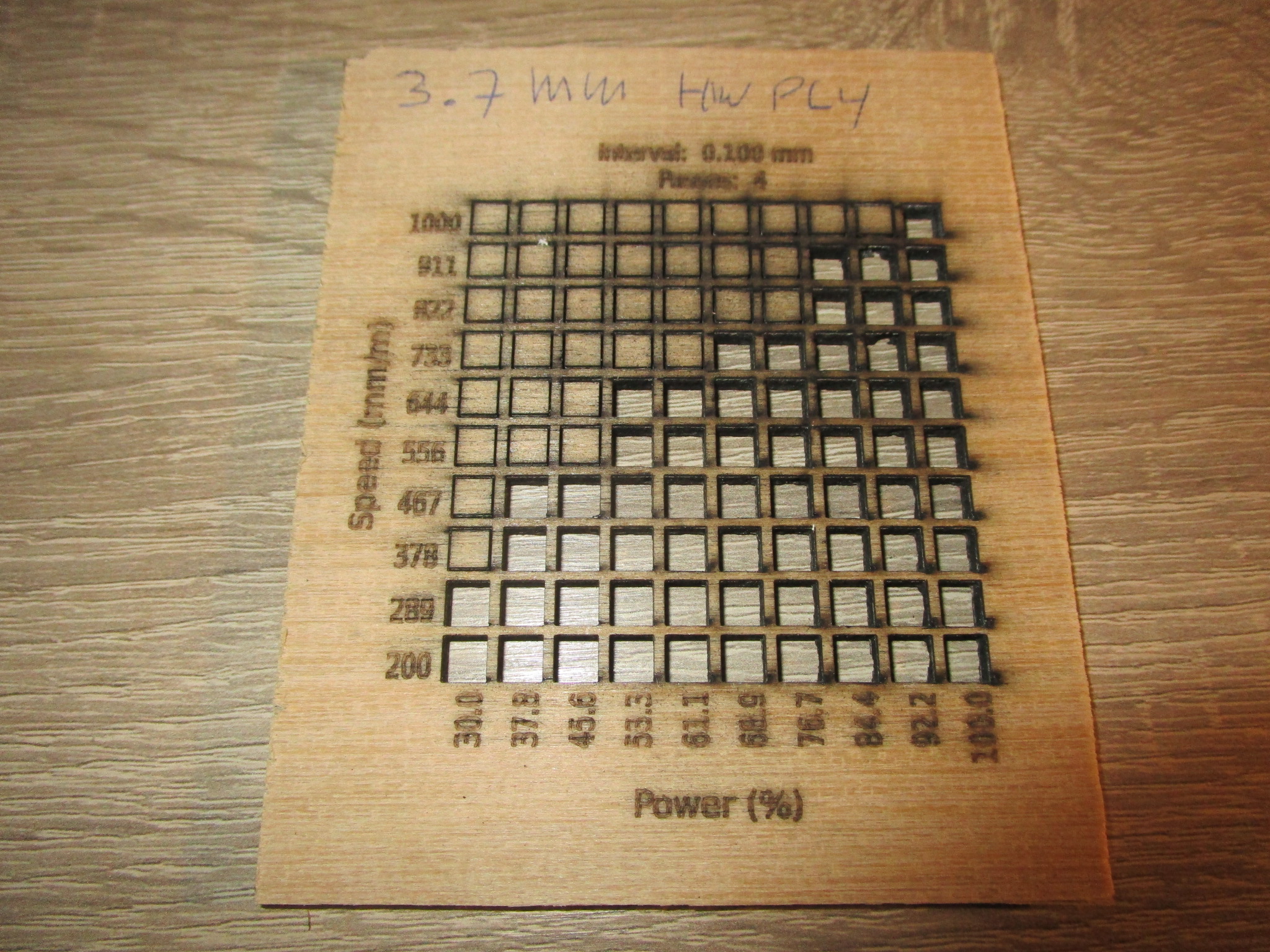

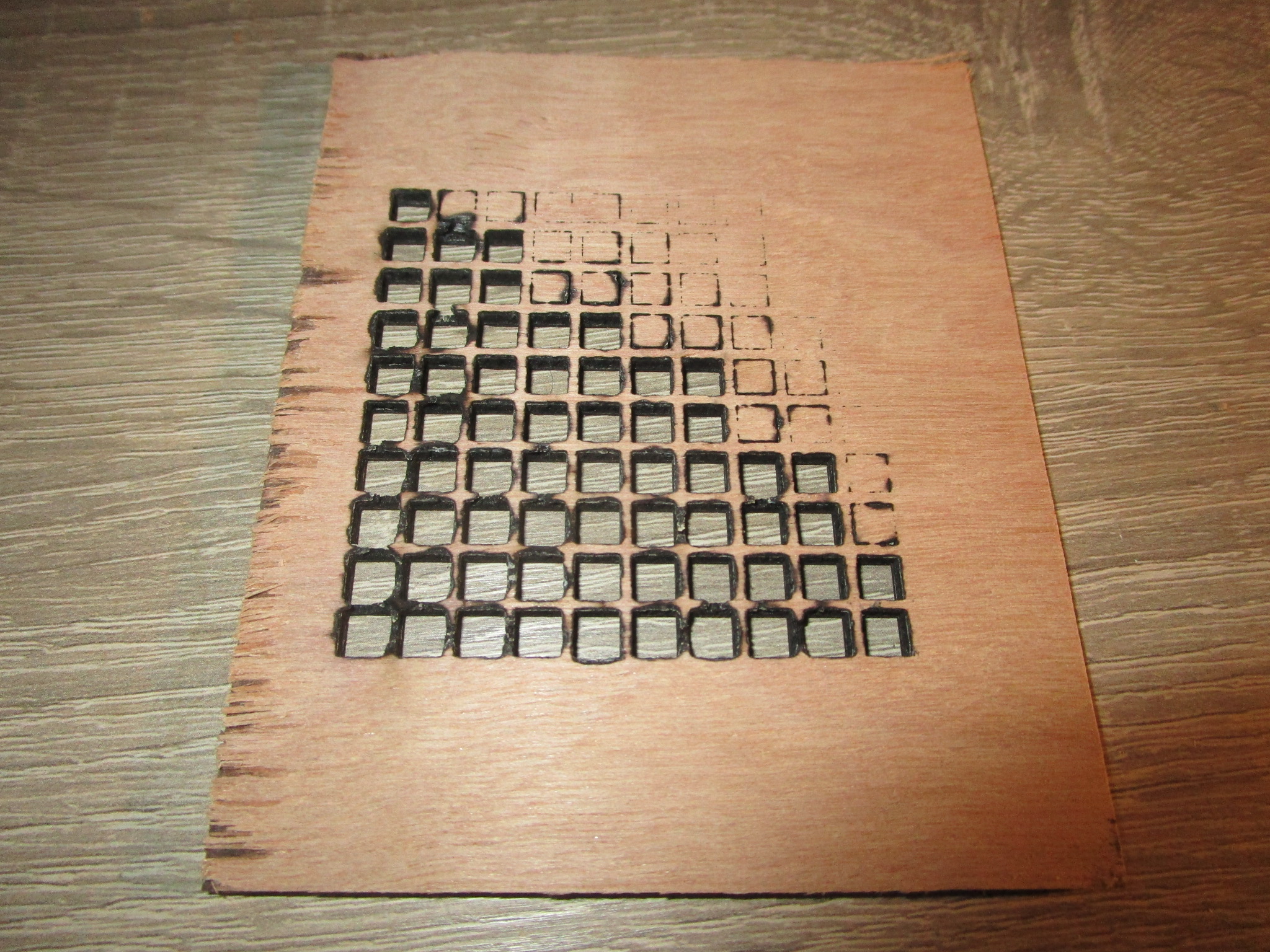

- 3.7 mm, 70% power, 200 mm/minute, single pass (not a very clean cut)

- 3.7 mm, 50% power, 600 mm/minute, 4 passes (cleaner cut, but a bit more charring at the top, should use masking tape)

- Thicker hardwood ply: terrible results, unusable.

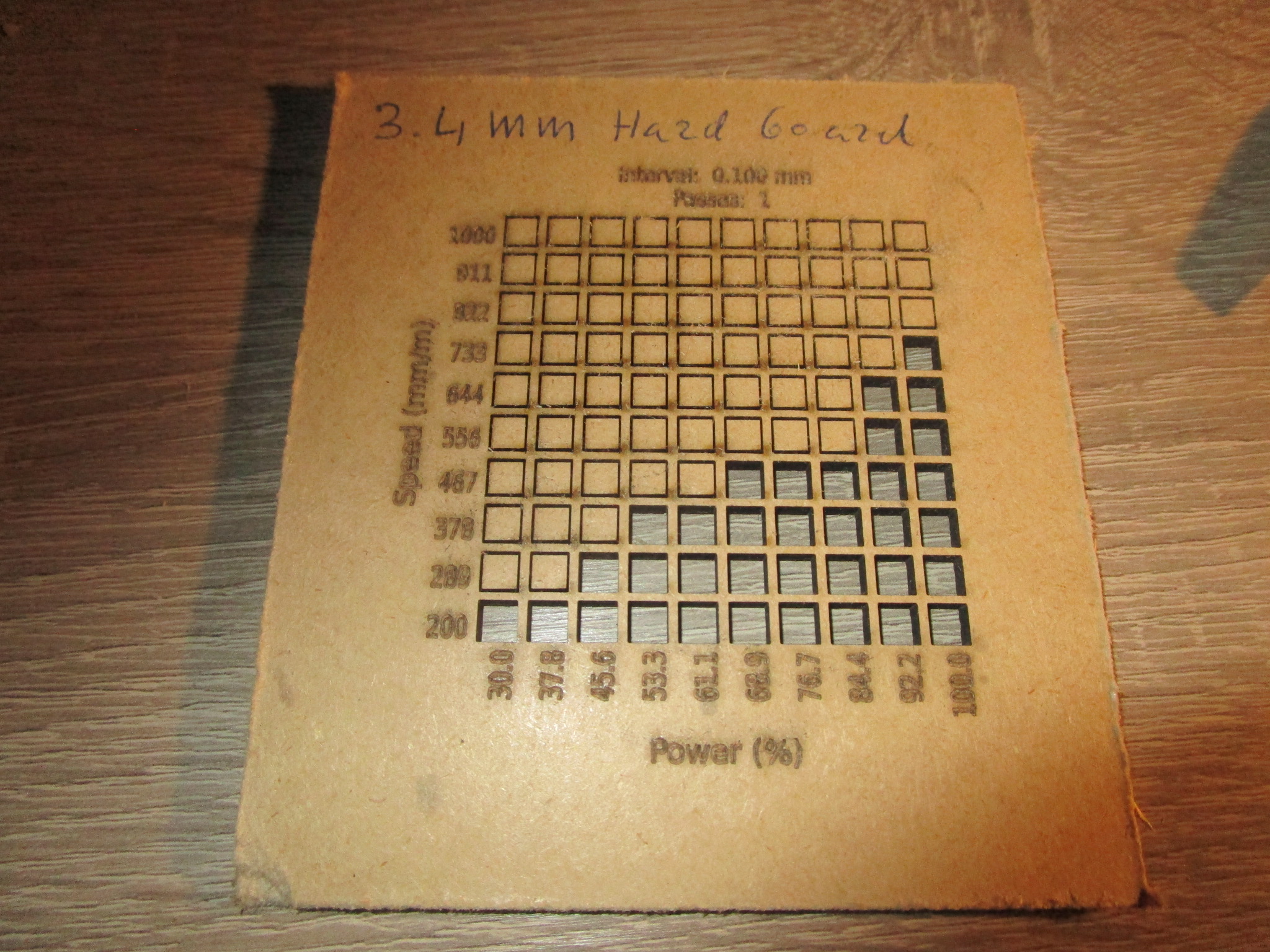

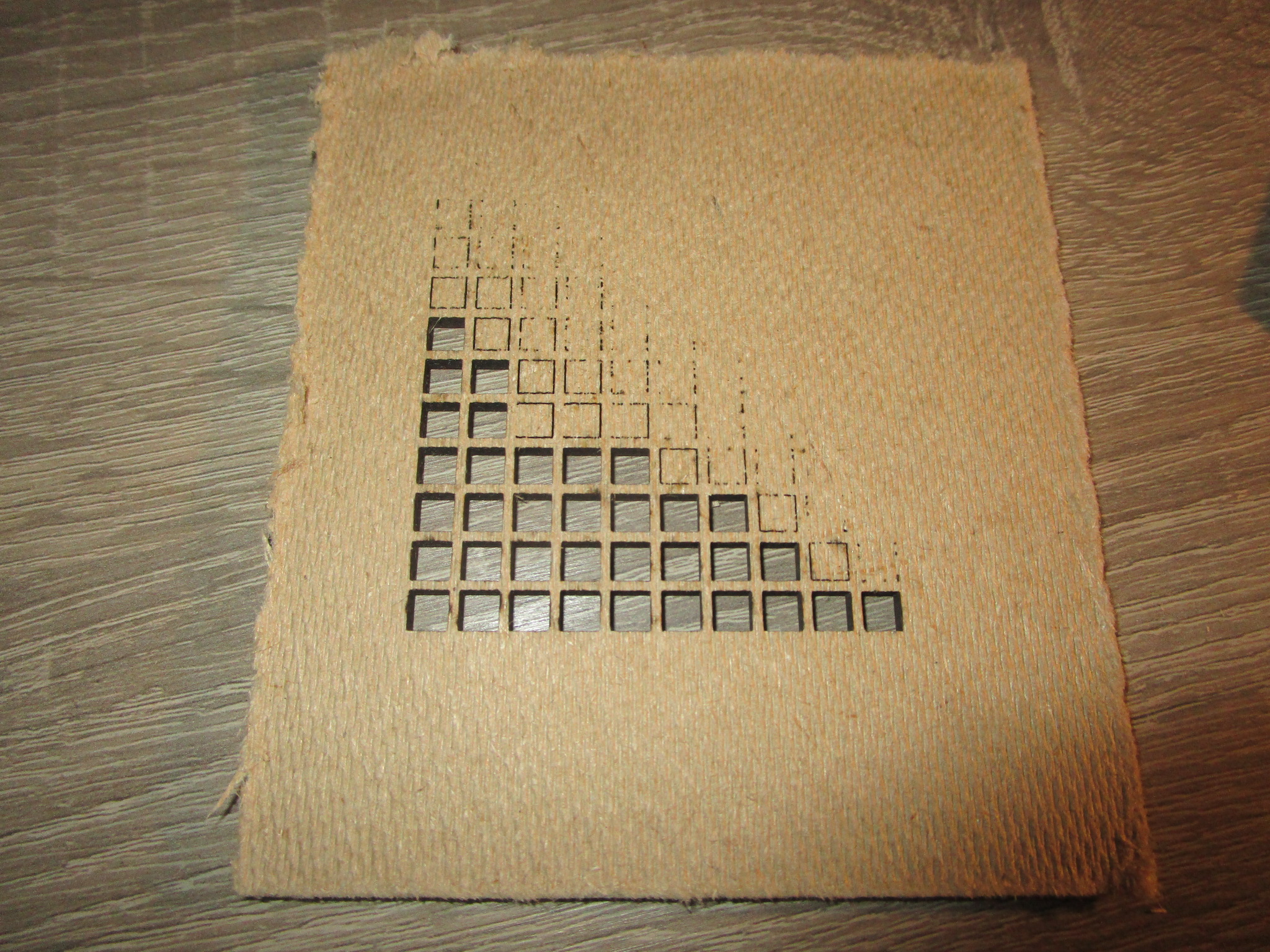

- hardboard

- 3.4 mm, 60% power, 450 mm/minute, single pass (for more speed: 100% power, 750 mm/minute)

- hardwood veneer

- solid hardwood

- Solid harder woods more than a few millimeters thick are difficult to cut using a laser. I’ve tried a few test pieces but nothing usable came out so far. It’s entirely possible that I need to change my approach to this and that the problem lies with me but I suspect that the density of the material is such that the laser simply doesn’t have enough power once you go out of the immediate focus of the beam and so you end up with very little depth of penetration. I intend to set up some tests to determine what exactly the limits are and whether or not something can be done about it.

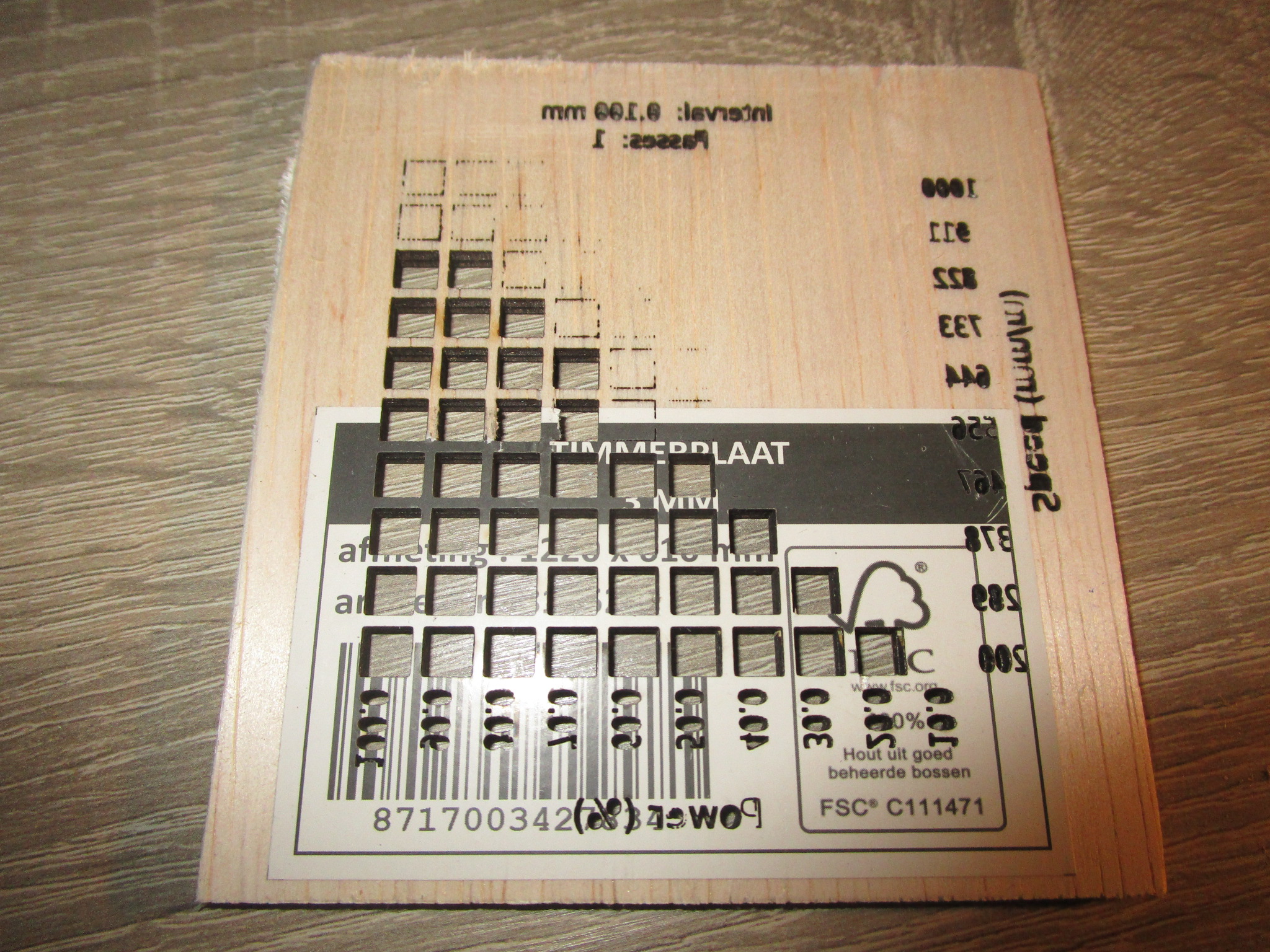

The following are materials test coupons made using a nominally 30W ‘Sculpfun’ S30 Ultra, it’s sold as an open frame machine with just about zero safety features for $1000 or less. Technically it probably shouldn’t be on the market at all, it is that unsafe but I’m happy that it is and with some work you can make it both safe to use and more effective than what you get out of the box. If you want to inspect a particular coupon more closely just click on the image to open it in a new tab.

| Material | Front | Back |

| 2.6 mm birch |

|

|

4.1 mm birch

Oops... |

|

|

| If you look closely you'll see that I forgot to reduce the power for the engraving so the letters have been burned clear through the material! |

| 5.5 mm birch |

|

|

| 7.8 mm birch |

|

|

| 12 mm birch |

|

|

18 mm birch

Some charring at the back, but usable |

|

|

| 3.2 mm coated MDF |

|

|

| 9 mm MDF |

|

|

| 3.7 mm hardwood ply |

|

|

| 3.7 mm hardwood ply, 4 passes |

|

|

| 3.4 mm hardboard |

|

|

Bamboo

I haven’t been able to get my hands on a suitable piece of laminated bamboo yet but it’s an interesting material and I expect it to work reasonably well, though the strong directional nature of the material may require some trickery to get it to work properly.

Paper/Cardboard

Paper and cardboard are fine to cut, you can use pretty high cutting speeds but air should be off to avoid blowing the material away. If you move too slow you’ll end up with too much charring on the edges. It may be possible to stack several layers on top of each other and cut them all at once. Be careful when using air in combination with paper or cardboard, it can hinder more than it can help and it can cause work pieces to be blown away. You can add some tabs to keep things in place but then you’ll have to cut these later to separate the work piece from the scrap.

- Corrugated cardboard

- 5.7 mm 3 ply packaging cardbord, 60% power, 1000 mm/minute, single pass. (for more speed: 70% power, 1400 mm / minute)

| Material | Front | Back |

| 5.7 mm corrugated 3 ply cardboard |

|

|

Textile

Organic textile tends to work very well, synthetic fabrics much less so, they tend to melt rather than cut cleanly and the results can be very messy (and hard to separate from the cutting bed).

Leather

I would highly recommend against cutting or engraving leather. It can be done but the results aren’t all that nice to look at and the smell is just horrible. If you want to make a lot of enemies in a short time however, cutting leather with a laser may just be the thing. Leather tanned with Chrome will release highly toxic vapors so unless you have material that is certified safe to be cut with a laser stay away from leather altogether.

Unless the metal is super thin it likely will not work well to be cut using a diode laser. I have yet to try some more exotic materials (such as Titanium) but all of my metal cutting experiments have ended in utter failure. Not a single successful cut, the best I achieved was some minor discoloration on stainless steel at maximum power. It is clear that the short wavelength of the laserhead that I’m using (455 nm) is too short for any serious metal work. A several KW fiber laser is ideal for this kind of work, it will cost a pretty penny and will probably arrive on a flatbed truck. You’ll need tri-phase power and you may need a permit to run one in a residential area because of the metal vapor. I would not recommend this unless you are sited in an industrial area (or in the middle of nowhere).

Anodyzed Aluminum

Some metal, notably anodyzed aluminum can be engraved quite well. You are essentially evaporating the layer on the aluminum exposing the bare metal underneath, which gives a nice effect. You could do the reverse, evaporate all of the cover except for where you want the pattern to appear but this will likely take a long time.

You could also use a marking spray, fluid or paste, these tend to be very expensive though and it may be worth researching alternatives.

Stainless Steel

Cutting stainless steel is probably out of reach for diode based systems, but you may be able to engrave them effectively.

Dykem Red engineering marking fluid makes for an excellent laser engraving on stainless steel, when using these low-power blue diode lasers. You just spray it on, engrave, and wipe off the excess with isopropanol(‘IPA’). The IPA can be a little difficult to remove, so warming it up helps, but it won’t wipe off where the laser has engraved it. It works well in a pinch and creates a nice, reddish permanent mark (that doesn’t come off in IPA).

Acrylic

Haven’t tried this yet but it will happen soon.

Polycarbonate

Hard no, you can not safely cut this with a low cost diode laser/air based system.

Most plastics & PVC

Plastics and PVC should not normally be cut with a laser, they will give off highly toxic vapors and the results will be sub-optimal. There is a fair chance that your work piece will end up welded to the bed (with the risk of damage to the bed) and that it will catch fire, you may not care about this while you are recovering in the ER (or when you’re not recovering in the morgue…). Seriously: stay away from most plastics and all PVC.

Stone & Ceramics

To be tested shortly

Delrin / Acetal

Expensive! To be tested (I first need to find some)

Other online resources

Tricks and tips

This section is dedicated to various little bits of knowledge that may help to extend the life of your machine, extend its capabilities or to make your life easier.

Thicker material

Cutting thicker material in one go isn’t always feasible. The temptation usually is to run the laser for multiple passes but beyond two or three of these it is pointless: the beam will diverge in the cut to the point that you’re only getting a minimal amount of power deeper in the cut (and you’ll be hitting the sides more than the bottom of the cut where you want to be). One way to get past this seemingly insurmountable limitation is to flip the material over and to cut a mirrored pattern from the other side. This ‘one weird trick’ instantly doubles the depth to which you can cut! Registration can be aided by pilot holes and a fixture mounted on the cutting bed. An easy way to achieve this is by sticking two pins (at least two!) through the material to be cut in such a way that when you reverse the material the pins will swap position. That way you have perfect registration provided you don’t move the pins (or the head!!) during the swap. Do remember to mirror the pattern on the second pass.

Laminate!

Another way to change the thickness of the resulting work pieces is by lamination. You cut identical patterns out of thinner wood which you then glue on top of each other under pressure to create a work piece that is much thicker than what your machine can normally produce. This for instance allows you to create hardwood gears from thin slices. Lamination is a very useful technique and if you get good at it you can produce work pieces that would require machines orders of magnitude more expensive than the ones you’ve got or that might be entirely impossible to make. You can also achieve interesting effects by purposefully offsetting the laminations (translation, rotation) or by ‘slicing’ a design in one dimension and then to glue the layers together to achieve a three dimensional effect. If you want to go fancy you could even sand down the steps of the slices to the point where you have a continuous surface.

You can add strength and precision to the laminations by adding registration holes that you hammer hardwood dowels into. This gives you almost perfect overlap between the layers (to within the precision of your machine) and the dowels have their grain oriented in a different axis to give your work piece more strength. Keep the dowels just a bit shorter than the total workpiece thickness so that you can still apply sufficient pressure during the glueing, and put some glue on the dowels as well while you’re at it.

More air

Air assist greatly improves cutting depth but the typical air pump that comes with a laser cutter is anemic and barely has enough airflow for the job. An entry level shop air compressor will do much better, but you’ll need to dry the air and make sure it is oil free. Take care not to overdo it, the hose needs to stay attached to the cutter head and you don’t want to end up cracking your optics. A typical laser head will use anywhere from 10 to 30 liters per minute, which the manufacturer supplied pump may not be able to provide. Some experiementation can help determine the optimum for your laser at a given power level. Higher power levels will tolerate more air, above a certain limit more air actually works against you because the material is cooled too much and below a certain limit you won’t be removing material fast enough to get the full benefit of the air. So there definitely is an optimal amount of air for any particular cutter/material/powerlevel combination.

Longer materials

If your enclosure permits it you may be able to use the registration trick on the same side of the material as well to create work pieces that are longer than the machine can comfortably cut in one go. You’ll need to move the entire support under the cutting head to make sure that you don’t lose the registration for the individual pieces (because presumably the laser has penetrated the material fully, so some of the work piece is now already cut).

Clean your optics!

It happens very gradually so you may not notice but typically it won’t take more than a few hours worth of cutting to have a measurable degradation in cutting power due to contamination on the focusing lens. You’ll eventually notice that you won’t be able to cut materials that you could cut before or that you will need to slow down too much. That’s a sure sign that your optics are not clean. I clean the optics on my machine prior to any major job, it usually takes less than five minutes and the results are so much better. Always be very careful when you put it all back together that you don’t end up cross threading the nozzle onto the head, this is very easy to do (fine thread, large diameter). The best way is to spin the nozzle counter clockwise until it ‘clicks’, this is a sign that the start of the thread has ligned up on both pieces and then to gently rotate the nozzle clockwise to screw it back on.