tldr: A small i386 32-bit protected mode multi-tasking operating system modeled after QNX

–

What is Unite?

Unite is an operating system in which everything is a process, including the things that you normally would expect to be part of the kernel. The hard disk driver is a user process, so is the file system running on top of it. The namespace manager is a user process. The whole thing (in theory, see below) supports network transparency from the ground up, you can use resources of other nodes in the network just as easily as you can use local resources, just prefix them with the node ID. In the late 80’s, early 90’s I had a lot of time on my hands. While living in the Netherlands I’d run into the QNX operating system that was sold locally through a distributor. The distributors brother had need of a 386 version of that OS but Quantum Software, the producers of QNX didn’t want to release a 386 version. So I decided to write my own. Luck had it that I ended up in Poland and that the lack of work there meant I could spend a lot of time on this (life was super cheap there back then compared to my savings). In the space of about a year I wrote a proof-of-concept kernel using DJGPP and a very kludgy development system that required me resetting the system after every failure. And there were lots of failures. Thousands of them, until, finally, one day I had a very rudimentary kernel and an ‘idle’ appliation running on top of it.

The next couple of years, until February 1994 (right after my first child was born and I decided I should probably get serious about earning money) I steadily improved on the original until it had a full complement of tools, was self hosting and came with a window manager and some graphics demos.

Why release this now?

When Linux was still very young, in 1992, there was a now infamous dispute between Andrew Tanenbaum, of MINIX fame and Linux Torvalds. The stakes were high: Tanenbaum thought Linus was wasting his time and talent building yet another macro kernel, he argued that micro kernels - even with a speed disadvantage - still have an edge in reliability and in speed of development. I agreed with Tanenbaum, but did not agree that MINIX was the way to go, I’d already seen QNX, and worked on my own variation on that theme and thought it was lightyears ahead of MINIX.

For the longest time this project sat on my hard drive in a state in which it could not run. The hardware that it had originally been developed on had died and I had never seen fit to spend more time on it to keep it bootable. Until the start of the fall of 2025, a good 30 years later, when I talked about it with my colleague I had not thought about putting any effort into a revival. In the meantime, a lot has happened. 32 bit systems are now already past, we’re on 64 bits now and 32 bit systems are usually doing only embedded stuff. We also have virtual machines, a luxury that my 30 year prior self would have happily traded a limb for, this makes development of such low level code a lot simpler than having to dive under the table every three minutes to hit the reset button. At some point this became such a routine that I hooked up a sustain pedal footswitch so I didn’t have to dive under the desk all the time.

So with modern tooling and the arena no longer vying for ‘the next best desktop solution’ I figured I should try to see if there is any life in it. Micro Kernels are fun to hack on: everything except for the core message passing task and scheduler is a user mode program and you can change it as easily as you can change any other program. That makes them unique and I think that this kind of hacking is now, especially with the more powerful embedded platforms within reach of just about anybody. The fact that it is a real time OS makes it much easier to work on hardware that requires guaranteed response time from the OS, there are 16 different priority levels and they offer very fine grained control over which tasks can be interrupted by which others.

Reviving an OS that hasn’t run in 30 years

This was a bit of a challenge. It took about two weeks, there were a couple of lucky breaks. The first was that I had not really done any cleaning of the repository where all this code was stored, so I had quite a few binaries that could run if I had a working OS. The second was that there was an image of a boot floppy. Between those two I managed to get the system booted under VirtualBox using a RAM disk. Some days later I had a working LBA capable hard drive, which I then populated with the contents of the ramdisk, and from there it was relatively quick work to recover the rest of the system.

The part that still eludes me is the bootfs.com program, this is the filesystem aware portion of the bootloader, that is loaded by the first stage on the boot floppy. There is some magic in there that for some reason does not play nice with the recovered version of TurboC, there is a chance I’m simply doing something wrong but I have not been able to successfully recompile that program and to get it to work so for now the system still boots from that original floppy image. But that’s fine, it’s not real hardware anyway and I’m sure if you really want to you can make it work again, all the pieces are there, I’ve added a VM disk image that should allow you to work on bootfs as well using freedos and some old binaries. Bootfs.com is a 16 bit real mode tiny memory model file that shuttles back-and-forth between real and protected mode to load all of the operating system components. It could boot from the hard drive as well (there is a ‘boot’ program to help you install the bootloader on an image) and like that you could do away with the floppy drive.

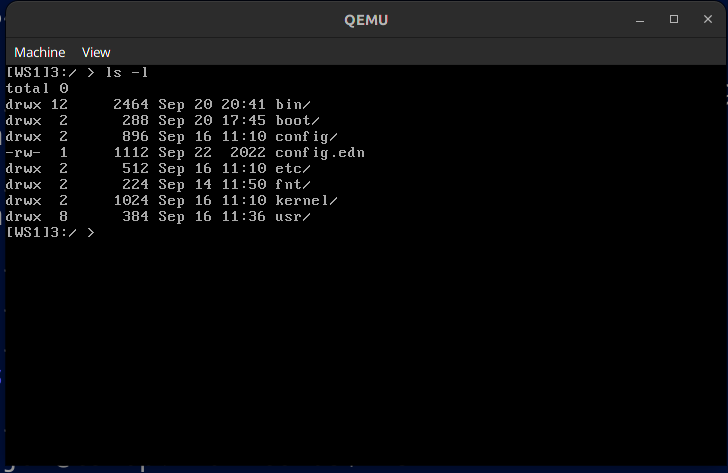

What does it look like?

Well, it looks like any old boring text mode operating system. There is the usual complement of utilities, a C compiler (and a C++ compiler), both are ancient but they work. There is the source tree in /usr/kernel.src and /usr/src as well as the usual unix like locations for binaries and such. There is a shell. There is some networking support but - again - I have not been able to resurrect this, and I can’t get the emulated COM ports to work either, which would have been nice as a way to move data in and out (for instance, using SLIP).

Quick start user guide

Install QEMU. Download the distro (see below). Unzip the distro file, and cd to unite/os, after that run ./unite.sh and you should see a virtual machine boot up in text mode. After it has booted and you’ve clicked in the VM windows to give it keyboard focus hit alt-f2 to move to another console (one where you can type commands) and type ‘cd 3:/’ to move to the hard drive. If you’re used to some variety of Unix you will feel mostly at home but note that ‘cli’ (command line interpreter) is not a regular shell. Interesting bits to look at are in 1:/boot/config.0 and of course the directory tree of drive 3:/ (the simulated hard disk). The file system is a very much stripped down version of the MINIX file system as it was at the time, it was meant to be replaced but I never got around to it. If you type ‘tsk’ you can see which tasks are currently running and ‘sac’ gives you a rudimentary system activity monitor. If you’ve used QNX at all in the past you will feel right at home.

Unite does not have the concept of a user, it is very much a single user OS but that single user can have multiple sessions. There is also a graphics mode, you can activate it by changing the ‘mode’ line in 1:/config/config.0 to ‘mode 16’ but I’d advise against that until you have the COM ports working and are able to type commands through there so you can see what you’re doing. If you are really adventurous: make a backup of the fda.img file; change that mode line and reboot. You’ll end up in a completely blind graphics mode. You should then type the following (all blind so you won’t know if you did it right or not until it works): ‘cd 3:/’ ; ‘cd bin/gp’ ; ‘ontty /dev/console.4 gp’ ; ‘ontty /dev/console.4 qwm’ ; ‘ontty /dev/console.4 qwmdesk’ (now the screen should change) ; ‘ontty /dev/console.4 qwmcalc’ (now you should see a small calculator, it would work if you had mouse/keyboard support but you don’t) ; ‘ontty /dev/console.4 qwmline’ (which should show a bouncing line demo).

Now you have a problem: if you reboot the system it will go right back to that graphics mode. So now you want to restore that fda.img backup you made above.

The Distribution

The operating system is distributed as a torrent:

magnet:?xt=urn:btih:bb01f5651944948b1b705ae4efa5ab5578bdee00&dn=unite.zip

The torrent contains a single zip file that you unpack, then you follow the instructions above.

Some notes:

I have only tested this under Linux using VirtualBox and Qemu, I have not ran it under a Windows VM or on real hardware and you may run into issues if you do.

there is no networking, this is probably the first thing that really needs doing

the COM ports don’t work yet (this seems to be an emulation issue, I have yet to see a single byte in or out)

the mouse driver (mp) does not work (it relies on a mouse plugged into a COM port, see above)

the version of vi that is in /bin seems to add random cruft to files, I have not been able to figure out yet what the reason for that is.

there is an alternative editor ‘e’ that does work, and that I wrote back in the stone age

this is not/was not an effort at making something that is ‘secure’, if you plan on using this be very much aware of that and that you are most likely going to open yourself up to being compromised within seconds if you hook this up to the big bad internet. I was already very happy that I got as far as I did. But the Micro Kernel concept lends itself well to modification and you can start hacking on the kernel pretty much immediately, it is that simple.

it is i386 protected mode only right now if you want another CPU or 64 bit then you have a lot of (fun!) work ahead of you.

I have plenty to do and will not be available to manage this project or to even administer it, the source code is my full and only contribution, from here on in if you want to do something with it you are essentially on your own (or with your friends!), I have a lot of other stuff on my plate that takes precedence, so apologies for that but I still hope you find this useful.

License:

There are a lot of pieces that have been cobbled together from various other distributions, these were all made available at the time so in theory they should be fine to use but I have not verified whether any of those licenses have since been retracted or modified. Whichever party contributed the code still has the rights and this release is under the exact same license as under which the code was originally released in the early 90’s. The remaining code, the part of the code that I lay claim to (the core OS, the editor and the graphics library) I herewith place in the public domain, you can do with it whatever you want, as long as you credit the project and include a link to this page so others can start off from the same point. If you release an interesting derivative let me know and I’ll add a link to this page.

Credits:

- Henri Groenweg wrote the memory manager

- Marcel Wouters wrote the console and display driver

- DJGPP, by DJ DeLorie was the key to being able to start this at all

- QNX served as a very useful model and inspiration

- MINIX, provided in source code made it possible to have a file system; so thank you Andrew Tanenbaum, this made a massive difference

Screenshots