Startup School Transcript

October 16 2010

Andrew Mason - Founder, Groupon

Link to video: http://www.justin.tv/startupschool/b/272180613

Startup School Transcript

October 16 2010

Andrew Mason - Founder, Groupon

Link to video: http://www.justin.tv/startupschool/b/272180613

[applause]

Andrew Mason: Hi, everybody. I’m Andrew. I asked Paul and Jessica what they thought I should talk about, and they thought the most useful thing, which I can totally understand, is kind of like talking about all the ways I screwed up and the failures, since a lot of you are probably struggling with the same sort of thing right now.

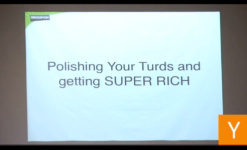

So, Groupon actually started out for a year, a year and a half, we were another service called thepoint.com, which was a much more abstract and broad version of what we are today. So, I thought what would be fun - and this is one of those ideas that sounds really good when you come up with it, but then in execution it usually sucks, we’ll see - would be to give you the pitch that I used to give for The Point when we were The Point, so I pulled together an old presentation that’s pretty similar to what I would have used for that. And then I’ll tell you all the reasons that that pitch sucks and that company sucks, and how we took those lessons and applied them to making Groupon kind of cool. So that’s why it’s called “Polishing your turds and getting super rich.”

So, Groupon actually started out for a year, a year and a half, we were another service called thepoint.com, which was a much more abstract and broad version of what we are today. So, I thought what would be fun - and this is one of those ideas that sounds really good when you come up with it, but then in execution it usually sucks, we’ll see - would be to give you the pitch that I used to give for The Point when we were The Point, so I pulled together an old presentation that’s pretty similar to what I would have used for that. And then I’ll tell you all the reasons that that pitch sucks and that company sucks, and how we took those lessons and applied them to making Groupon kind of cool. So that’s why it’s called “Polishing your turds and getting super rich.”

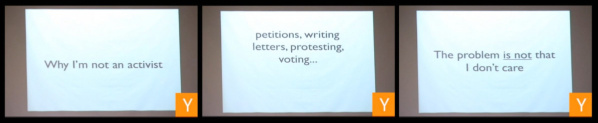

Alright, so, The Point. The Point is a company, a website that is designed to solve the problems of collective action, getting a group of people to do something that one person can’t achieve alone. And I thought I’d start by articulating the problems with collective action by using myself as an example. I’m not an activist, I mean, I read about issues, I care about issues, I wish I could make a difference, but I think the reason I’m not an activist is that I’m not sure what I could do that could actually make a difference. The options that are out there, for me, aren’t interesting. For example, why would I go stand in a-, go to a protest when I could go be a freelance developer something, and make enough money in a day and take five college kids and send them to the protest instead. [laughter] So, the problem isn’t that I don’t care, I just don’t know what I could actually do that would lead to results.

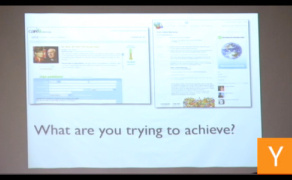

And if you look at petitions, so many of them, you look at them, what exactly is this going to achieve? So here is a causes thing - by the way, this presentation is circa mid 2008, so some of the content is going to be a little dated, like Sarah Palin stuff, although, unfortunately that’s not dated, I guess. [laughter] So, stop global warming. Everybody joined a petition to stop global warming, that feels really good, but what’s it actually going to do?

And if you look at petitions, so many of them, you look at them, what exactly is this going to achieve? So here is a causes thing - by the way, this presentation is circa mid 2008, so some of the content is going to be a little dated, like Sarah Palin stuff, although, unfortunately that’s not dated, I guess. [laughter] So, stop global warming. Everybody joined a petition to stop global warming, that feels really good, but what’s it actually going to do?

Protests. This is a protest called The March For Women’s Lives, I think, it was in 2004, it might have been the largest protest or organized gathering in history with over a million people, but it was also one of the least covered. It was just no interest, for whatever reason, it was raining or something, and just the press didn’t cover it. So when your tactics for creating change are at the mercy of PR, it’s just like you are throwing shit on the wall and hoping that people pay attention, then it’s not a very rational-, it’s not necessarily going to lead to results.

Protests. This is a protest called The March For Women’s Lives, I think, it was in 2004, it might have been the largest protest or organized gathering in history with over a million people, but it was also one of the least covered. It was just no interest, for whatever reason, it was raining or something, and just the press didn’t cover it. So when your tactics for creating change are at the mercy of PR, it’s just like you are throwing shit on the wall and hoping that people pay attention, then it’s not a very rational-, it’s not necessarily going to lead to results.

So the Internet came along, and the Internet should solve all the problems of organizing people and changing collective action. But the problem is, all we’ve done is we’ve taken the old world tactics that we used offline and ported online. We haven’t really changed the way we think about things. So, for example, here is a protest against the Iraq war that people held in Second Life. [laughter] I call these tactics the tactics of inconveniencing yourself, because all these things, signing a petition or going to a protest, they’re all like mini versions of lighting yourself on fire. [laughter] They’re saying, I will sacrifice a small part of my life to show you how much I care, and that just feels so futile and not very exciting to get to be part of. And the weird thing is if the tactic you’re using is inconveniencing yourself, all the Internet does is make it easier to sign petitions, so by making it easier to inconvenience yourself, you’re making your effort more and more meaningless, right. So, if it only takes one click to write a letter to your congressman, then it takes an order of magnitude more letters for them to actually care.

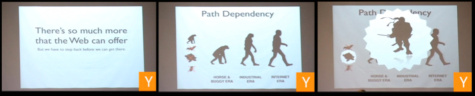

Now, there’s so much more that the Web could potentially do, but we have to step back before we can get there. We’re in a state of path dependency where we just look at what we did before and we continue to evolve off of that. So, we’ve all kind of evolved from apes, right, and that’s where, that’s why we have online petitions now. But the Internet introduces new realities and we have to ask ourselves, if we had those realities from day one, like, maybe we would have evolved in a different direction. If we had the technology, maybe we’d all be like that. [laughter]

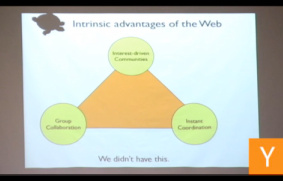

So what are the intrinsic kind of advantages that the Web provides? Here is a few: interest driven community, so you’re not just organized around-, by people in your immediate geography, you can organize with other people who care about the same kind of things. Group collaboration, crowdsourcing, wikis, all that stuff, coming together and finding a collective solution to a problem. And instant coordination, the ability to-, I mean Twitter, right, the ability to come together and make a decision as a group. None of that existed when people decided to invent petitions in the first place. So that’s when The Point comes in.

So what are the intrinsic kind of advantages that the Web provides? Here is a few: interest driven community, so you’re not just organized around-, by people in your immediate geography, you can organize with other people who care about the same kind of things. Group collaboration, crowdsourcing, wikis, all that stuff, coming together and finding a collective solution to a problem. And instant coordination, the ability to-, I mean Twitter, right, the ability to come together and make a decision as a group. None of that existed when people decided to invent petitions in the first place. So that’s when The Point comes in.

The idea of the point is that anyone can start a campaign to organize a group of people around a shared result that they want to achieve, and they all agree to take action or give money towards something, but only once they reach a tipping point, such that their contribution actually makes a difference. So, the anatomy of a campaign is you have an objective. For example, your objective might be, say, the oil company is dumping waste in the lake, and you want them instead to develop proper waste disposal facilities, so your objective is develop those facilities. People make a pledge, the pledge might be we’re going to stop patronizing this gas company, we’re going to stop buying gas from them, and the tipping point would be the point at which the total cost of your collective action is greater than the cost of change. So, for example, in that example would be how many-, what’s the value of a customer to the oil company, and how many of those people you need to offset the value of building waste disposal facilities. So that would be your tipping point. When you get that number of people, you take action. So that was the idea of The Point, and here is a few examples of why-, of how it can be used.

So, to use the Sarah Palin example again, here’s something where people are trying to raise money to put an add in the newspaper, where you get a group of people together to create their add. So, let’s see. There are rational incentives for change, like we were talking about before. So, here’s people who are saying we’re going to stop eating at KFC once we can get a million people enough, unless they’re willing to adopt the suggestions of the Animal Welfare Board, so it’s enough people, customers that they would lose to offset the cost of implementing the suggestions. So, it makes rational sense, as a participant you can see why you might want to join. Here is another one, where a group of people have organized a discount at a local business where if they can get thirty people to come in, then it’s worth it for the business to offer it at a lower price.

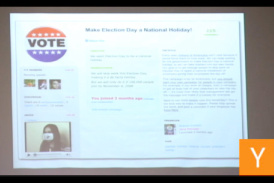

Safety in numbers. So, here is a bunch of people that are trying to make election day a national holiday. If they’re going to get a hundred thousand people together, they’re just not going to come to work. So, if you were trying to make election day a national holiday by yourself and you didn’t come to work, you’d get fired, but if enough people do it, then you have king of a safety in numbers.

Safety in numbers. So, here is a bunch of people that are trying to make election day a national holiday. If they’re going to get a hundred thousand people together, they’re just not going to come to work. So, if you were trying to make election day a national holiday by yourself and you didn’t come to work, you’d get fired, but if enough people do it, then you have king of a safety in numbers.

Finally, it enables longshots, things that would just never occur otherwise. So this is a campaign to create a dome over the city of Chicago  [laughter] and we need ten billion dollars to do it, and people can put their credit card in and contribute money, but you’re not charged until you hit that tipping point. So, the cool thing about it is allows you to separate, like, will this happen from what would it be worth to me. If you just say to someone what would it be worth to me to make (( )) in Chicago, ten thousand dollars, no problem, and you know you’re not on the line unless you actually get enough to make it happen.

[laughter] and we need ten billion dollars to do it, and people can put their credit card in and contribute money, but you’re not charged until you hit that tipping point. So, the cool thing about it is allows you to separate, like, will this happen from what would it be worth to me. If you just say to someone what would it be worth to me to make (( )) in Chicago, ten thousand dollars, no problem, and you know you’re not on the line unless you actually get enough to make it happen.

OK, so I’ll cut the point presentation off there, and also say that was a terrible presentation, like, you should never give a presentation like that, when you only-, you don’t even show the product, you show it like ten minutes into the presentation, so that’s one kind of side. So, we did-, we launched The Point in fall of 2007 and we screwed around with it for a year, didn’t really get any traction, and started thinking about making kind of fundamental changes. And we thought about what are the really interesting applications of this, and one of them was this collective buying idea, and we built The Point so you could take these little flash widgets and embed them wherever you want in the Web, like a YouTube video, so what we did was we created this thing called Groupon and everyday - this is a Wordpress blog - and we would do a new post everyday and embed a different campaign widget from The Point. That was us from fall of 2008 through like early summer of 2009 with this little bullshit thing that I whipped together in a month. But it worked.

OK, so, now I’m going to go through some of the lessons that we’ve learned that allowed us to be, I think, successful with Groupon where we failed with The Point. This first one, you’re not building a piece of art, it’s a tool, and for me, like, when I originally had the idea for The Point, it started off as I was frustrated because I had to pay an early termination fee from the cell company, and everybody had that problem, I wished there was a way that we could all come together and just say we’re not going to pay this fee, you can’t charge us all if we all refuse to pay. And then, the more I thought about it, I realized you could abstract that model and apply it to everything from organizing a small group of people that buy a ping-pong table for their dorm, to boycotting multinational corporations, to group purchases for your local business, to funding a local park, and it became this vision of an idea like a book. It became much more about being truthful and a complete representation of what the idea was than it was actually building something that was going to be useful. In fact, this down here, just to show you how extreme it was, we did a video, I did a video of myself in the year 2015 talking about a world where The Point was fully mature, that I then sent back in time [laughter] to share with people, as a way to, like, it was so much more about the vision than it was about figuring out how to make something useful.

OK, so, now I’m going to go through some of the lessons that we’ve learned that allowed us to be, I think, successful with Groupon where we failed with The Point. This first one, you’re not building a piece of art, it’s a tool, and for me, like, when I originally had the idea for The Point, it started off as I was frustrated because I had to pay an early termination fee from the cell company, and everybody had that problem, I wished there was a way that we could all come together and just say we’re not going to pay this fee, you can’t charge us all if we all refuse to pay. And then, the more I thought about it, I realized you could abstract that model and apply it to everything from organizing a small group of people that buy a ping-pong table for their dorm, to boycotting multinational corporations, to group purchases for your local business, to funding a local park, and it became this vision of an idea like a book. It became much more about being truthful and a complete representation of what the idea was than it was actually building something that was going to be useful. In fact, this down here, just to show you how extreme it was, we did a video, I did a video of myself in the year 2015 talking about a world where The Point was fully mature, that I then sent back in time [laughter] to share with people, as a way to, like, it was so much more about the vision than it was about figuring out how to make something useful.

Now, with Groupon, it was the total opposite, it was, get away from the abstract and recognize that whatever you’re building, you have about one second for people to look at and decide if it adds utility, and that’s what Groupon was. I mean, even the whole collective buying thing is really minimized in our presentation, it’s progressively disclosed, you might realize-, when you show up, you just see half of a restaurant that’s awesome, and then, once you buy, it’s like, oh, we still need another thirty people to join, that’s cool.

Recognize and embrace your constraints. We totally didn’t do this with The Point, I mean, with examples like trying to build a dome over the city of Chicago, I mean, what was our plan to make that happen, it would just go viral. And, honestly, when I created that campaign, I thought it would happen, I really, I honestly thought [laughter] there was a chance it could happen. So, I learned this thing to embrace your constraints from Scott Heiferman at Meetup. This is-, I just put this together for the slide, but this is a rough version of how he described to me what the first version of Meetup was. It was just a matrix of cities and of interests, and then you decide which one you’re interested in, so if I’m interested in food in San Francisco, I click sign up and it would say, OK, the meetup in your city is at Starbucks at this corner, and we meet on the first Tuesday of every month, and if four people sign up, there’s a meetup, if not, then not. So, I think what Scott recognized is that it was going to be really hard, especially at the beginning, to get organizers, to get the human that’s going to set all this stuff up and make those decisions about exactly what day it should be on, what should the location be. So he built-, he really simplified it, took away all the complexities and just built this simple matrix that would allow it to start getting some traction. And we did the same kind of thing with Groupon, I mean, it’s the whole business model, all the decisions we made were largely around living with the constraints that we had. We had this collective purchasing platform, but we didn’t have customers and we didn’t have supply. We didn’t have inventory and stuff to sell, so we decided let’s start in Chicago because we can go to local businesses and get them to sign up, and let’s only do one deal a day because that’a all the deals we could really get. It was as simple as that, it was around-, it was the only way that where a community was so small that we would have to channel the entire force of that community into one thing in order to get enough critical mass for the business to be willing to offer discount.

Recognize and embrace your constraints. We totally didn’t do this with The Point, I mean, with examples like trying to build a dome over the city of Chicago, I mean, what was our plan to make that happen, it would just go viral. And, honestly, when I created that campaign, I thought it would happen, I really, I honestly thought [laughter] there was a chance it could happen. So, I learned this thing to embrace your constraints from Scott Heiferman at Meetup. This is-, I just put this together for the slide, but this is a rough version of how he described to me what the first version of Meetup was. It was just a matrix of cities and of interests, and then you decide which one you’re interested in, so if I’m interested in food in San Francisco, I click sign up and it would say, OK, the meetup in your city is at Starbucks at this corner, and we meet on the first Tuesday of every month, and if four people sign up, there’s a meetup, if not, then not. So, I think what Scott recognized is that it was going to be really hard, especially at the beginning, to get organizers, to get the human that’s going to set all this stuff up and make those decisions about exactly what day it should be on, what should the location be. So he built-, he really simplified it, took away all the complexities and just built this simple matrix that would allow it to start getting some traction. And we did the same kind of thing with Groupon, I mean, it’s the whole business model, all the decisions we made were largely around living with the constraints that we had. We had this collective purchasing platform, but we didn’t have customers and we didn’t have supply. We didn’t have inventory and stuff to sell, so we decided let’s start in Chicago because we can go to local businesses and get them to sign up, and let’s only do one deal a day because that’a all the deals we could really get. It was as simple as that, it was around-, it was the only way that where a community was so small that we would have to channel the entire force of that community into one thing in order to get enough critical mass for the business to be willing to offer discount.

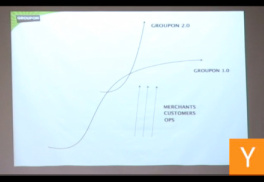

So, now, we’re in a different reality where we have different assets than we had when we started the business, and completely different problems. We have, in other words, the opposite problem, so more merchants than we can serve. Our biggest problem as a business is the fact that we have a six month backlist of businesses that want to be featured, which has lead to the proliferation of these clones just to (( )) up all the people that we can’t serve. We have tons of customers, and we have operations, we have a 2500 person staff, 1600 sales people around the world, customer service and editorial, we have this kind of deal creating machine. So, if we started the business with all these assets, we might make different decisions. And what we’re working on now, the kind of product we’re trying to build is one that reimagines the business as if we had-, this is how it always was. So you can see we have this Groupon 1.0, and this Groupon 2.0, which is stuff that we’ll be releasing over the coming months. But you can’t get to Groupon 2.0 until you get along a certain curve in Groupon 1.0, you know what I mean, does it make sense? Kind of.

So, now, we’re in a different reality where we have different assets than we had when we started the business, and completely different problems. We have, in other words, the opposite problem, so more merchants than we can serve. Our biggest problem as a business is the fact that we have a six month backlist of businesses that want to be featured, which has lead to the proliferation of these clones just to (( )) up all the people that we can’t serve. We have tons of customers, and we have operations, we have a 2500 person staff, 1600 sales people around the world, customer service and editorial, we have this kind of deal creating machine. So, if we started the business with all these assets, we might make different decisions. And what we’re working on now, the kind of product we’re trying to build is one that reimagines the business as if we had-, this is how it always was. So you can see we have this Groupon 1.0, and this Groupon 2.0, which is stuff that we’ll be releasing over the coming months. But you can’t get to Groupon 2.0 until you get along a certain curve in Groupon 1.0, you know what I mean, does it make sense? Kind of.

Have a growth plan. From the beginning we built into the model for Groupon how we were going to reach scale: through e-mail marketing, largely. We knew that we were going to have crappy deals up from time to time, and it was going to be hard to get people to come back again and again to the site, so, instead, let’s get them signed up on an e-mail list, let’s not push them to the deal, let’s push them to the sign up form for the e-mail list, because once they’re engaged on e-mail, then, you know, you can send them crappy deals three or four times before they want to unsubscribe, you get more chances before they tell you to screw yourself. We obviously didn’t have that with The Point. I mean, how was this [presentation slide shows the previously mentioned Chicago Dome cause / thepoint.com] going to happen, seriously, how in the world did I think it was going to happen? [laughter]

Have a growth plan. From the beginning we built into the model for Groupon how we were going to reach scale: through e-mail marketing, largely. We knew that we were going to have crappy deals up from time to time, and it was going to be hard to get people to come back again and again to the site, so, instead, let’s get them signed up on an e-mail list, let’s not push them to the deal, let’s push them to the sign up form for the e-mail list, because once they’re engaged on e-mail, then, you know, you can send them crappy deals three or four times before they want to unsubscribe, you get more chances before they tell you to screw yourself. We obviously didn’t have that with The Point. I mean, how was this [presentation slide shows the previously mentioned Chicago Dome cause / thepoint.com] going to happen, seriously, how in the world did I think it was going to happen? [laughter]

The best tools aren’t always cool. The shiny object. So, e-mail, right. I would take one e-mail address over ten Twitter followers any day, or ten Facebook fans. E-mail just works really well for our business. What else? Sales people. I think maybe this is being from Chicago, but we view the idea of self-service with the same skepticism that someone from Google probably views the idea of hiring a sales person. And that’s part of what’s made our business successful, in order to achieve real ubiquity with local merchants, you need to have a sales force and we’ve invested in that. For PR, for getting the word out on your business, we actually-. How many of you actually heard of Groupon first from your girlfriend, or your mom, or something [raises hand]. So that’s probably more than four square, right. We designed it that way, we specifically decided not to go after, like, the TechCrunch, to get posted on TechCrunch, because we knew the moment it would happen, all of you vultures [laughter] would come along and abandon your fledgeling social network for dogs to chase after whatever our thing. [laughter, applause]

The best tools aren’t always cool. The shiny object. So, e-mail, right. I would take one e-mail address over ten Twitter followers any day, or ten Facebook fans. E-mail just works really well for our business. What else? Sales people. I think maybe this is being from Chicago, but we view the idea of self-service with the same skepticism that someone from Google probably views the idea of hiring a sales person. And that’s part of what’s made our business successful, in order to achieve real ubiquity with local merchants, you need to have a sales force and we’ve invested in that. For PR, for getting the word out on your business, we actually-. How many of you actually heard of Groupon first from your girlfriend, or your mom, or something [raises hand]. So that’s probably more than four square, right. We designed it that way, we specifically decided not to go after, like, the TechCrunch, to get posted on TechCrunch, because we knew the moment it would happen, all of you vultures [laughter] would come along and abandon your fledgeling social network for dogs to chase after whatever our thing. [laughter, applause]

So, finally, this is a really important one. When I was working on The Point, I had this stupid attitude, like, if you build it, they will come, nothing can go wrong, I can go and-. Here is another question, this is the last time I’ll do this: how many of you - raise your hand if you are the smartest person you’ve ever met. [laughter] Alright, how about if in the last year you still thought you were the smartest person you ever met. [holds hand up] No? OK. So, my theory is that a lot of kids who are starting startups are people who have had blessed lives, who have achieved everything they’ve ever done, and just failure doesn’t seem realistic to them, like they’ve never confronted real failure and looked it in the eyes and accepted it as something that could happen. I don’t think you have to fail, I think you just have to realize that it could happen, because it shapes the way you make decisions. With The Point everything was, all the decisions I was making were around of course this is going to work, I can’t go wrong. With Groupon, even to this day, I’m thinking about all the ways I could screw up and how to avoid that. I think the best thing, the best trait as a CEO is the fact that I think I suck as a CEO, because it means I surround myself with people who make up for all those things, and we have a great team, and so on.

So, finally, this is a really important one. When I was working on The Point, I had this stupid attitude, like, if you build it, they will come, nothing can go wrong, I can go and-. Here is another question, this is the last time I’ll do this: how many of you - raise your hand if you are the smartest person you’ve ever met. [laughter] Alright, how about if in the last year you still thought you were the smartest person you ever met. [holds hand up] No? OK. So, my theory is that a lot of kids who are starting startups are people who have had blessed lives, who have achieved everything they’ve ever done, and just failure doesn’t seem realistic to them, like they’ve never confronted real failure and looked it in the eyes and accepted it as something that could happen. I don’t think you have to fail, I think you just have to realize that it could happen, because it shapes the way you make decisions. With The Point everything was, all the decisions I was making were around of course this is going to work, I can’t go wrong. With Groupon, even to this day, I’m thinking about all the ways I could screw up and how to avoid that. I think the best thing, the best trait as a CEO is the fact that I think I suck as a CEO, because it means I surround myself with people who make up for all those things, and we have a great team, and so on.

So, this is a picture from the lobby of Groupon when you walk in. We were on the cover of Forbes a couple of weeks ago, and you can see that in the middle, and then surrounded by it are other magazine covers with MySpace, and Napster, and AOL, and Friendster, all those other failed businesses [laughter]. So, every time something great happens I kind of look at it as my responsibility in the company to scare the shit out of people and remind them that there are a lot of people who have been in our place before (( )) the story doesn’t end up as rosy.

And finally, you should quit now, because everything you go through is going to be telling you that over and over again. I mean, there are moments in our history when we were working on The Point that every sign pointed to quitting. It was totally irrational for us to keep going, we had so little, it’s just that we were stubborn and we just refused to quit. And that’s what the process is going to be like. It’s unbelievably hard, and you work non stop, and anything that-, like, for me, as a human being, I feel like I’ve been raped of any personality. I mean, I used to be able to have a social conversation with people normally, but I’ve forgotten what it’s like, because all I think about in my brain is Groupon, and when this is over I don’t know if I’m going to be able to go back to being a normal person. [laughter] Like, this weird thing happened a couple of days ago, I discovered Gmail shortcuts, keyboard shortcuts, and for the next few days I was just like happy. [laughter] And I was, like, what is this feeling, it’s so rare. [laughter] I’ve forgotten what it’s like to be happy, and something like Gmail shortcuts make it happen. So, I say quit now, because if that actually works, then you should. Anyway, that’s the end of my presentation, so I’ll take some questions if anyone has any. I think, do I have time? OK. [points at audience]

And finally, you should quit now, because everything you go through is going to be telling you that over and over again. I mean, there are moments in our history when we were working on The Point that every sign pointed to quitting. It was totally irrational for us to keep going, we had so little, it’s just that we were stubborn and we just refused to quit. And that’s what the process is going to be like. It’s unbelievably hard, and you work non stop, and anything that-, like, for me, as a human being, I feel like I’ve been raped of any personality. I mean, I used to be able to have a social conversation with people normally, but I’ve forgotten what it’s like, because all I think about in my brain is Groupon, and when this is over I don’t know if I’m going to be able to go back to being a normal person. [laughter] Like, this weird thing happened a couple of days ago, I discovered Gmail shortcuts, keyboard shortcuts, and for the next few days I was just like happy. [laughter] And I was, like, what is this feeling, it’s so rare. [laughter] I’ve forgotten what it’s like to be happy, and something like Gmail shortcuts make it happen. So, I say quit now, because if that actually works, then you should. Anyway, that’s the end of my presentation, so I’ll take some questions if anyone has any. I think, do I have time? OK. [points at audience]

Audience: How much have you (( ))?

Andew Mason: The Posies situation is a business that had-, that was overwhelmed by the amount of demand they had on Groupon, it didn’t feel like they should do it again. So, the vast majority of businesses that are featured on Groupon, we survey every business ((with over)) three thousand results, 95% are satisfied. So, if there was a story written for every local merchant that regretted their decision to do newspaper advertising, there would be nothing else in the newspaper. So, we look at it as let’s minimize that percentage of people that had a bad experience, let’s invest in having world class merchant services, let’s educate people about this new model of local commerce. But it doesn’t scare me, I mean, I believe in what we’re doing.

Audience: (( ))

Andew Mason: Sure, it wasn’t a black and white switch, actually, this is interesting. It was kind of like grass growing, where one day it’s , like, oh, my gosh, we’re spending all our time on Groupon. So, actually, a lot of the core development team continued working on The Point, and then I was working on this blog, and I built a file maker app to distribute all the coupons, and that’s what we were doing, and then, slowly, it was more and more, it became more and more valid to invest in spending time on Groupon. And two things, I mean, the success we were having with it were energizing in a way that the whole team just got behind it very quickly, and the second thing is that, while at first we looked at it as a service that, I mean, it was the tail that wagged the dog, it was going to bring in money while we solved the world’s unsolvable problems working on The Point. We started to feel like, I mean, when we started hearing feedback from the merchants and customers, we realized, ironically, that we were doing far more good with Groupon than we ever had, and probably ever would with The Point. So that allowed us to really get behind it and really get excited about it.

Audience: (( ))

Andew Mason: Advice on early employee hiring. Avoid ((tidals)), you know, stuff as much as you can, I guess. Do them if you have to in order to hire, but don’t create too much structure around that stuff because you may need to make changes later. Probably other advice, too, but for whatever reason I thought of that piece of advice. [pointing to the audience] You, on that side, the green shirt.

Audience: Now that you’re rich, how do you feel about activism?

Andew Mason: I never really cared about activism. [laughter] I care about social engineering and doing things that make a big difference, and activism happens to be an area where you can have a big impact. That’s not entirely true, but I like the way it sounds.

Audience: It seems like some of the (( )) may make sense in Groupon 2.0 in that line curve that you drew, you know maybe Groupon 1.0 maybe needed to focus (( )) broader action (( ))?

Andew Mason: Right, so he said some of the broader focus of The Point might actually make sense in a Groupon 2.0 world, and I agree with that, I mean, the greatest problem with Groupon is how do you get to scale, it’s the classic chicken and egg, oh, sorry, The Point, is how do you get to scale, and we never had a solution for that. So, all the examples that I talked about when I was pitching the business, and the ones that we tried to go after were these massive change initiatives, and the small ones just weren’t nearly as interesting to people.

Audience: (( ))

Andew Mason: By building an awesome product. I mean, just the lead that we’ve managed to maintain in the face of thousands, I think, hundreds of clones, I mean, I think speaks to the passion we have for building something that’s awesome, and just an awesome customer experience. I think all these ideas around network effects are overrated, I mean, it’s nice to have that kind of such stuff strategically built in your model, but how did networks effects get MySpace, you know. There’s more examples of businesses with those network effects getting overtaken by somebody who out-innovated them than otherwise. I mean, think eBay is a good example of someone where-, almost the exception that proves the rule where the network effects are so strong that they could just survive off of the (( )) they had.

Audience: How did you evolve (( ))

Andew Mason: It started that way from the beginning. I played in a band with one of our community managers at The Point in college, and he was just a funny guy and he started doing the writing, and we always had a firm belief in building a product that we wanted to use, and part of that was creating awesome editorial copy that didn’t feel like people were reading advertising. And as we’ve grown, actually, the increasing pressure that there is to conform to the way that businesses typically behave, is just a greater motivation for us to act out and be weird. So we now do things like we launch this thing called Grouspawn, which is a scholarship fund for children to get a full college scholarship if their parents met using a Groupon. [laughter] So, this is one of those things where I say, I mean, you could, I could pretend like the reason to do that is to help the kids, but I just think it’s funny to create these awkward first interactions on a date, where, like, you’re having a great date and someone pulls a Groupon, and it’s like you have to confront the issue of having babies. [laughter] So, it’s fun to run a big company, you should do it.

Audience: (( ))

Andew Mason: That’s not true. But what we do do is sustainable. Yes, next question. [laughter]

Audience: (( ))

Andew Mason: Equity. I mean, they’re (( )), so a lot of their commission plans are based off the commission plans we had when we thought we’d be doing, you know, a hundred thousand dollars of revenue a year in one of these cities, so they make a ton of money. Oh, we had money, so we gave people salary and everything, and then we just paid them off a commission, we had raised the money.

Audience: (( ))

Andew Mason: Our writers, not yet, but we’d love to. And it’s just one of those, when you’re growing as fast as we are, stuff like that, and some A/B testing, also any kind of internal facing optimization, we put off. So we do stupid things, like, we have a staff of ten people probably copying the records out of the sales force manually into indoor Groupon platform, just because it’s not worth our time to take one of our engineers for a week and have him tied to the ((API)). Right there, did you have a question? No, he doesn’t.

Audience: (( ))

Andew Mason: The advantages are that, I mean, I was lucky to get tapped into a very entrepreneurial group in Chicago with my co-founders, I mean, I wouldn’t have been able to do any of this if I didn’t have the co-founders that I have. I mean, they came to me and said, why don’t you drop out of school and turn this into a company, I’ll give you a bunch of money, and I was like, people do that, that’s crazy. I didn’t know what VC was, what angel capital was or anything, it’s not part of the culture the way that it is here. So Chicago has been great for a business like ours where it’s largely a hybrid technology-human business, right, we have 2500 people, maybe a hundred of them are in engineering, everybody else is doing other stuff. The downside is, while there is engineering talent in Chicago, it’s a shallow pool, so we’ve kind of reluctantly realized that we have to have an office out here and hire engineers out here. That’s it, thanks guys. [applause]